If I were to ask you to name any famous Czech composers of the late 19th century you might quickly say Bedřich Smetana, or Leoš Janáček, or even Gustav Mahler. (I admit Mahler is a bit of a stretch since most people think of him more as German than as Czech. I suspect this is because, although he was six months old when his parents moved from Kaliště to the Bohemian town of Jihlava 125 km or so southeast of Prague, he left there at age 15 or 16 to enter the Vienna Conservatory and, as the German speaking son of Jewish parents, felt himself, “always an intruder, never welcomed.” Also, unlike the others, he didn’t build his oeuvre on Czech themes.)

However, I’d also guess that, particularly for most Americans, Antonín Dvořák

[Photo of Dvořák from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

comes readily to mind because while he, like the others, had close ties to his homeland he also had ties to the U S. And it was to the Dvořák Museum

Jana would take us after our time at Vyšehrad.

A bintel bio.

Antonin Dvořák was born on 8 September 1841 in the Czech village of Nelahozeves about 21 kilometers northwest of Prague. Although his father operated two businesses, working as an innkeeper and a butcher, he was only marginally successful at these preferring instead to play and practice the zither which he also did professionally. So, while the young Antonin spent some time as an apprentice in his father’s butcher shop, he was exposed to a passion for music almost from birth.

Dvořák received his first formal training from his elementary school teacher Josef Spitz who instructed him on the violin and in singing. When he was 12, he moved to Zlonice living with an aunt and uncle. It was here that Antonin Liehmann provided lessons on the piano and organ and it was here that Dvořák composed his first song – the Forget-me-not Polka.

After spending a year in Böhmisch Kamnitz (today called Česká Kamenice) mainly to learn German, he enrolled in the Institute for Church Music in Prague when he turned 16 and graduated second in his class in 1859. However, this didn’t help him get hired as a church organist.

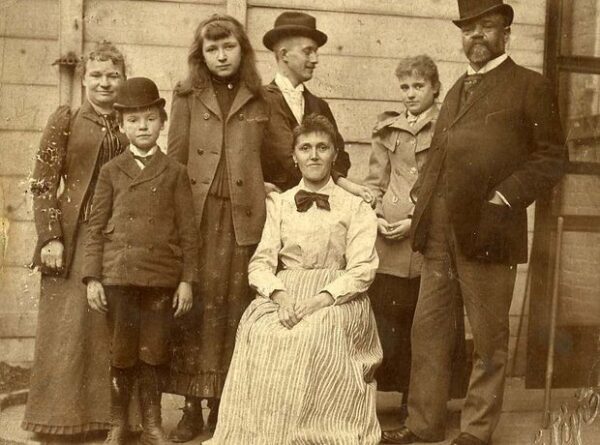

Instead, in 1862, he became the principal violinist for the orchestra of the newly formed Czech Provisional Theater – a position he held for nine years – and during which time it premiered three Smetana operas. Still, he needed to supplement his income by teaching piano. In 1864 two of his students were Josefina and Anna Čermáková, fifteen and ten years old at that time (seen here in 1868).

[Photo of Josefina and Anna Čermáková from dvoraknyc.com].

Like Mozart a century before him, he fell in love with Josefina who rejected him in much the same way that Aloysia Weber did Mozart. In 1873, also like Mozart a century before him, he married her younger sister.

(According to Josef Suk, Dvořák’s son-in-law and himself an accomplished musician and composer, the extensive passage of poignant nostalgia at the conclusion of Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor (B. 191), completed in 1895, was composed as a memorial to Josefina who had died in May of that year. This passage includes a quotation of Dvořák’s song Leave Me Alone (B. 157, Number 1), which according to his biographer Otakar Šourek, was a special favorite of Josefina’s.)

Dvořák generally struggled to find success as a composer until his works caught the ears of a fellow in Vienna named Johannes Brahms. In 1877, Brahms convinced his publisher Fritz Simrock to publish what became known as the Moravian Duets. Simrock then commissioned Dvořák to compose the first of his two sets of Slavonic Dances conceived as piano duets. The sheet music for the first eight dances sold out on the first day. His orchestrations later in 1879 propelled him to world renown.

A whole new world.

Like many great composers, Dvořák was focused more on his art than his finances. In June 1891, Jeannette Thurber, President of the National Conservatory of Music of America, offered him a post as composition teacher and school director in New York. The salary she proposed was $15,000 per school year roughly equivalent to $500,000 and 25-30 times his pay at the conservatory in Prague. It took months of prodding by Anna before he accepted and even then from January through May 1892 he engaged in a farewell tour of more than 40 Bohemian and Moravian towns before he finally departed for New York.

In all, Dvořák spent three school years and a total of 31 months in America from September 1892 through April 1895. During that span he spent a long summer vacation period in 1893 in Spillville, Iowa (described on its website as, “…a village founded by a German that grew into a refuge for Czechs.”) probably at the invitation of his friend and student Josef Kovařík who had been born there.

[Photo of Dvořák and family in Iowa from classicFM].

That summer Dvořák also visited Omaha, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Chicago where he conducted a concert of his compositions at the World’s Columbian Exposition. He also stopped in Niagara Falls on his return trip to New York City and, on seeing the falls, is reputed to have said, “Heavens, definitely a symphony in B minor!”

Because his use of themes from traditional Czech folk music pegged him as a nationalistic composer, among the projects Dvořák was, at least informally, tasked with completing was creating an American national music. Once in the States, he became fascinated with African-American spirituals and, to a lesser extent, Native-American music as well. He controversially asserted that these should provide the main sources for such national music.

A partial list of his compositions while in residence in the United States includes the Concerto in B Minor for Cello and Orchestra, String Quartet #12 in F major “American”, String Quintet #3 in E-flat Major also called “American”, the American Flag Cantata, and of course, the Symphony #9 “From the New World.” While these might not have become quintessentially American music, they certainly influenced its development.

In athletics, people sometimes talk of someone’s coaching tree. This applies to the lineage that began with one head coach whose assistants coaches became head coaches who then themselves developed more head coaches. In the case of Dvořák. perhaps even more important than the music he composed was his compositional tree. As the Dvořák American Heritage Association writes,

Dvořák’s composition pupils had an impact on the further development of music, in this case most remarkably via their pupils: his student Will Marion Cook became the teacher of Duke Ellington, Harry Rowe Shelley taught Charles Ives, and Rubin Goldmark taught both Aaron Copland and George Gershwin. More generally, Dvořák’s public declarations of appreciation for African American music may have given broad encouragement to the development of jazz.

The last might be a bit overstated but certainly worth considering.

I have a few final words about Dvořák because he had some rather curious obsessions. The first is that for much of his life he was a train spotter. Some say that was because the construction of the railway connecting Prague with Dresden passed through Nelahozeves when he was four or five years old. You can read about that in more detail here. Regarding his fascination with trains, he once said,

It comprises so many parts, so many different components, and each has its own importance, each has its proper place. Even the smallest bolt is where it is meant to be and fastens something together! Everything has its purpose and role and the result is astounding. This engine is then set on its railway track, they pour coal and water into it, a man pulls a small lever and then the big ones start to move and, even though the carriages weigh several thousand hundredweight, the engine speeds along with them like a hare. I’d give all my symphonies if I could have invented the locomotive!

After his sea voyage from Europe for his residency in New York, the composer developed a new fascination, steamships and pigeons. You can read about that in this article titled Classically Curious: Pursuing passions with Dvořák in the Big Apple.

No money but lunch at Mincovna.

After our visit to the Dvorak Museum, we returned to Old Town and marched down to Staroměstské náměstí or Old Town Square where we had a group lunch at a restaurant called Mincovna which, as nearly as I could work out from good old Google translate means “mint” but in the sense of a place where money is fashioned rather than meaning the plant (which is máta). I had the good fortune to sit with Jana where I learned how to order jedno malé pivo – or a small beer – and the proper way to make a toast. I knew the words – Na zdraví – but not the gesture of tapping glasses against each other then on the table. Potato mushroom soup and cauliflower latkes accompanied my jedno malé pivo.

I have lots of ground to cover on my free afternoon so stay tuned.