In various emails and Tweets I promoted my previous posts as a teaser trailer – not very cinematic perhaps – but very much a teaser and, having read them, you might feel that I did, indeed tease you. That ends today. It’s time for act one of the feature presentation – a tour of Machu Picchu. In this post, I’m going to write about some of the site’s structures and report on the views historians and archaeologists have on the methods of construction, the likely purpose each structure had, and their determinations regarding the purpose of the entirety of the complex. Before I start along those paths, I want to clarify a misconception that I believe many people have.

I think it’s fair to say that this –

or some similar photo is among the iconic images people have when they think of Machu Picchu. While it is a photo of a large section of the complex, what it is not is a photo of Machu Picchu. To understand this, you need to recall three facts from previous posts. The first is that Machu Picchu means Old Mountain in Quechua. The others are that Machu Picchu is the name Hiram Bingham, III gave to the site and that we don’t know its true name. The prominent peak in this photo is called Wayna Picchu which is Quechua for Young Mountain. This

is Machu Picchu – the Old Peak. So now, you too, can be a snooty smart ass if you want.

Probably not a city.

Before we start walking, let’s begin with an overview. It’s clear that Machu Picchu was carefully designed. However, in much the same way that the Forbidden City in Beijing isn’t truly a city but was instead the home of the imperial palace for the Ming and Qing dynasties, it’s likely that Machu Picchu also was not a city. I previously cited a National Geographic article in which some researchers have concluded that Machu Picchu was built as a retreat for Pachakutiq and perhaps others in the nobility. The same article notes that Luis Lumbreras – at one time the Director of Peru’s National Institute of Culture – sees it as a site that fulfilled ceremonial religious functions. In truth, it’s reasonable to conclude that it served both purposes.

This guide, from Machu Picchu Pass

provides a sense of Machu Picchu’s layout and highlights many of the sites within it that I’ll describe in more detail. (I’d encourage you to visit Wikipedia’s page to see some spectacular panoramas from Machu Picchu.) Including both the urban and agricultural sectors, the entire site covers an area of approximately 32,600 hectares. The area deemed the urban sector occupies less than eleven of those hectares so its relatively small size supports the notion that Machu Picchu should not be considered a city. The urban sector is believed to have been further divided, much like Cusco, into an upper town and a lower town. (Many of the site’s structures are in the typical kancha design I described in writing about Cusco.) The religious, royal, and astronomical sites (mainly on the left on the guide) occupied the upper town with warehouses and worker’s living quarters comprising the lower town.

In another National Geographic article about Machu Picchu, Brian Bauer, a specialist in Andean civilizations at the University of Illinois at Chicago, posits that the site was relatively small by Inkan standards with a population usually less than 1,000. Farming terraces in the immediate vicinity were likely insufficient to sustain even a small population and most specialists in the field believe that sites such as Winay Wayna contributed crops from its community to serve the elites at Machu Picchu.

After spending years studying high altitude Inkan ceremonial sites, National Geographic explorer-in-residence Doctor Johan Reinhard, concluded that Machu Picchu was constructed in the center of a sacred landscape. If that’s the case, this centrality might have motivated Pachakutiq to build his retreat in this place. Reinhard reached this conclusion by combining archaeological and ethnographical studies with historical sources.

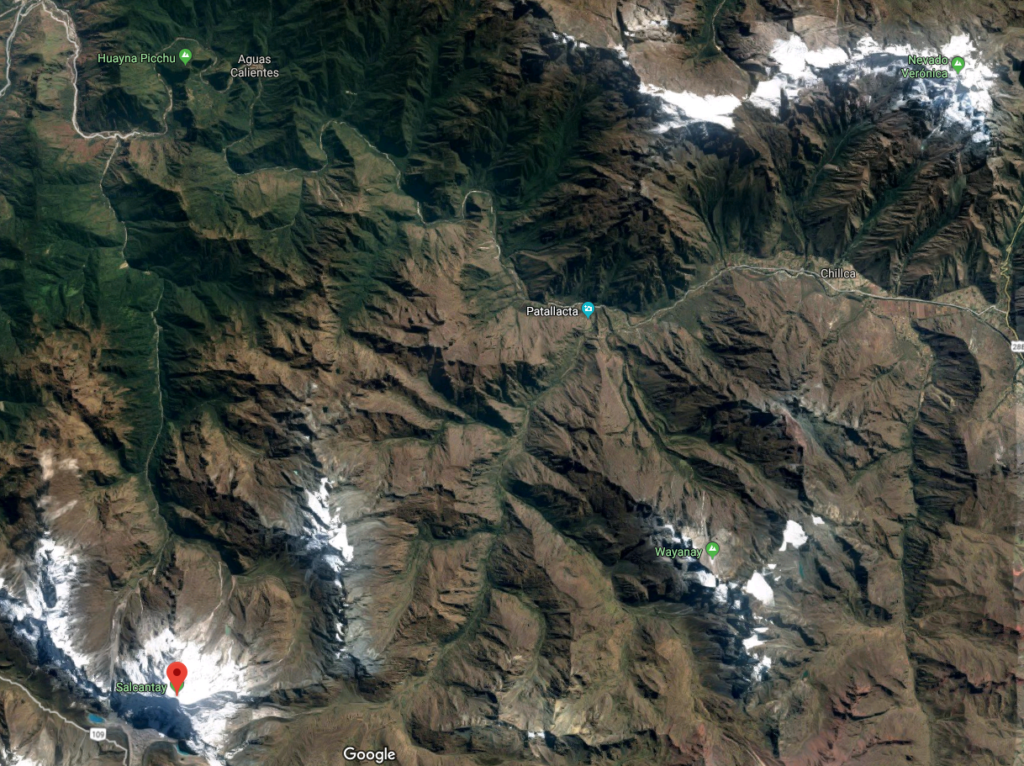

[Screenshot of Machu Picchu {at top} from Google Maps.]

He points first to the Wilkamayu (Urubamba) River, that nearly encircles the citadel and is still considered sacred by many indigenous people. Almost certainly Wayna Picchu would have been considered a sacred mountain particularly given that it’s believed to have been the residence of the high priest and that it’s the site of the Temple of the Moon. The latter is built in a shallow mountainside cave at an altitude a little below that of the citadel itself.

Other nearby peaks also have special importance. These include Salkantay to the south and at 6,271 meters the highest peak in the area, Pumasillo or the puma’s claw to the west, and Waqaywillka (possibly derived from the Quechua for crying rock). Waqaywillka (called Verónica in Spanish) is generally easily visible as one looks eastward from Machu Picchu and, when viewed from there, the sun rises from directly behind its highest point on the equinoxes. Likewise, the constellation we call the Southern Cross, some form of which also appears to have held a degree of significance for the Inkas, rises on the east and sets on the west of Salkantay.

Various mountain gods, including those associated with these peaks, held a special place in the cosmology of the Inkas. Reinhard concludes, “Taken together, these features meant that Machu Picchu formed a cosmological, hydrological, and sacred geographical center for a vast region.” Even if it’s not certain, it’s certainly a credible conclusion.

We’ll begin our walk around the complex in the second portion of this newly shortened post.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

You rock! Thanks so much for taking the time to share your adventures with all of us.

As you’ll see, it’s more like I disco.