Heartless Mountain – part 2

Memory, history and healing.

Construction of the camp at Heart Mountain, the fourth largest relocation center in the U S, began on 15 June 1942.

(Heart Mountain can’t technically be called an “internment camp” because internment refers to a lawful process for detaining people – particularly resident aliens. The Japanese Americans were not detained under the law, and the majority of those detained were U S citizens. A more accurate term would be “concentration camp” because all the camps concentrated a single ethnic group in a confined space. Most literature avoids that term because of its association with Nazi death camps and, while these camps were unlawful, they were far from death camps.)

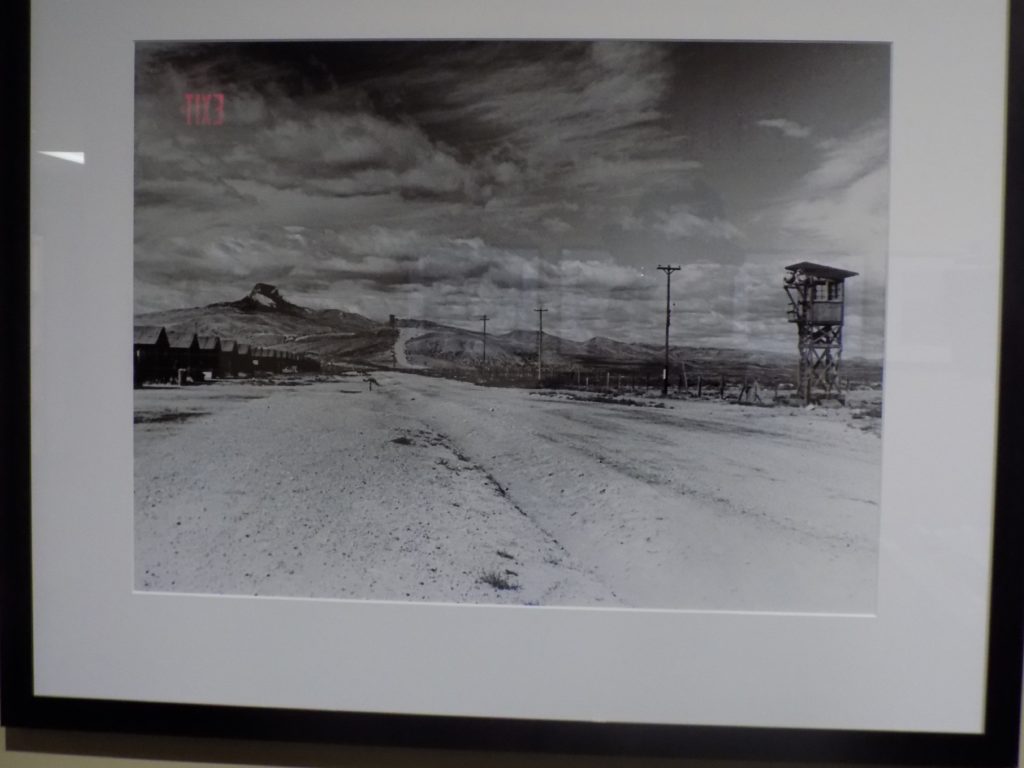

By November 1942, barbed wire and nine guard towers encircled the 46,000-acre facility. While much of the land would be used for farming, approximately 740 acres would be used to house a population exceeding 10,000 in a planned 650 structures. The first group of nearly 300 Japanese Americans arrived on 11 August 1942 and worked to prepare the camp for the additional arrivals.

The Heart Mountain camp, named after the Heart Mountain Butte, rising 8 miles to the west, was a flat, treeless landscape covered in buffalo grass and sagebrush that received only a small amount of precipitation annually. The area was hot and dry in the summer, and cold and windy in the winter.

Of the 650 planned buildings, 467 barrack-style buildings were completed and sectioned into 20 blocks that served as administration areas and living quarters. Covered only with tarpaper, the barracks were divided into apartments, some single rooms, and others slightly larger to accommodate families of up to six. Each unit was furnished only with a stove for heat, a light fixture in the center of the room, and an army cot with two blankets for each person. Each block had a mess hall, unpartitioned toilet and shower facilities (one for each sex), and a laundry area.

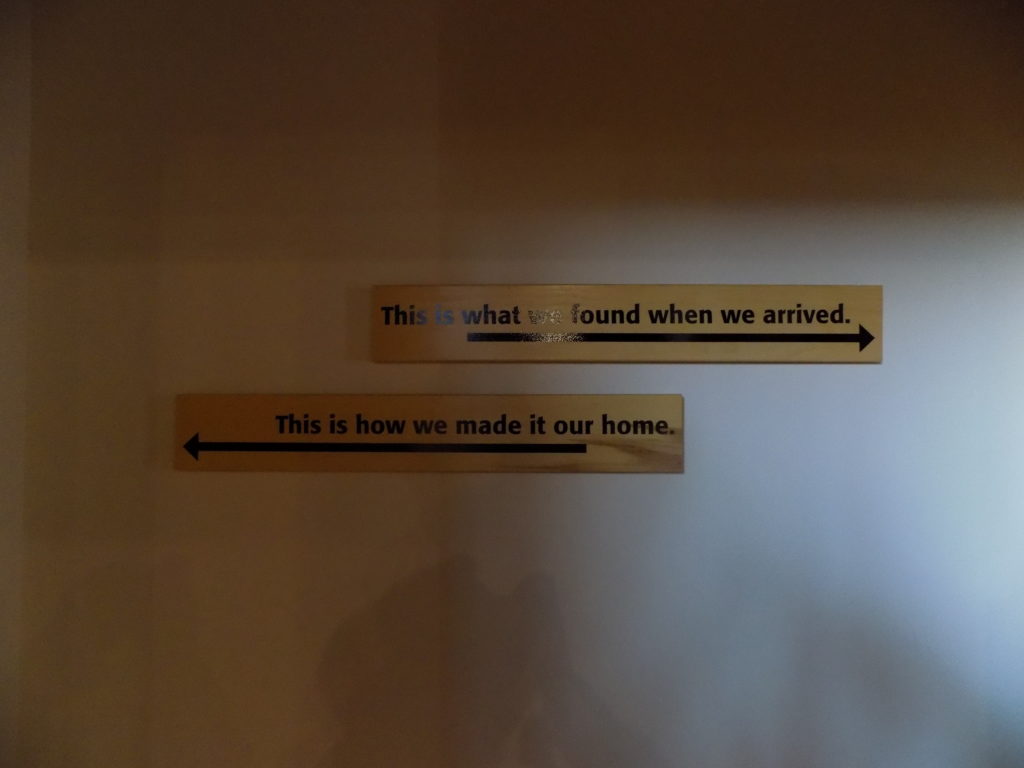

One of the displays at the Heart Mountain Interpretative Center shows one way the Japanese tried to make the best of a difficult situation.

This picture follows the right pointing arrow

and this, the left.

Another way the camp administrators and parents tried to provide some sense of normalcy was through their children. Children continued their education and the high school even had a football team that competed against teams from area schools willing to come to the camp. The camp administrators also helped to organize Cub Scout and Boy Scout troops for the boys and Campfire Girls, Girl Scouts, and Brownie troops for the girls.

For the adults, however, the situation was quite different. Only older Nisei were permitted to work. They could hold paid jobs in farming, the motor pool, mess halls, and fire and police departments where they earned between $12 and $19 monthly. For most Issei, the camp experience was one of forced idleness. Depression wasn’t uncommon and it led in many instances to a breakdown of family structure. Many of the men never recovered and struggled to reintegrate into their communities after the camps closed. (One enterprising man built a darkroom under his bunk and shot more than 2,000 pictures of life at the camp. You can see some of his story in the video below.)

In a bit of irony, Roosevelt reinstated a draft of Japanese Americans on 20 January 1944. Many internees protested this as unfair and unconstitutional because of their confinement during the war. The Heart Mountain camp became the site of the largest single draft resistance movement in American history. Known as the Fair Play Committee, it was a membership organization of draft-age Nisei men who advocated for a restoration of their civil rights as a precondition for compliance with the military draft. Eighty-five of the resistors were tried, convicted, and then imprisoned for draft evasion. At the same time, others who had been confined at Heart Mountain not only served but served with honor including two who received the Medal of Honor. One of them, Norman Mineta,

served 10 terms in the U S House of Representatives and was Secretary of Transportation for George W Bush.

More than 14,000 people passed through the Heart Mountain camp and at its population peak, it was the third largest city in Wyoming. Today, the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center serves as a moving reminder of the dangers of demonization and xenophobia.

You might notice that the butte for which the camp was named doesn’t appear in any of my photos. The ash obscured it.

Chasing that vision of light.

My time at Heart Mountain had left me pensive on my drive back to Jackson and Grand Teton National Park. It had been an emotional morning so as I retraced my drive – winding my way back through Yellowstone National Park, I reached a decision to take at least a small hike in the Tetons hoping some time in nature would revitalize my spirits – ashes, ankle, and altitude be damned.

Arriving at the park, I consulted my National Park Service hiking guide and settled on the climb to Hidden Falls and Inspiration Point concluding that it would be the most appropriate given the time of day. It was also a wise choice because this is considered one of the less strenuous hikes in Grand Teton and, while the Aleve had done its job, I remained unsure whether it might simply be masking the pain of a more severe injury.

I was fortunate enough to find a parking space on the main lot by Jenny Lake and purchased a round trip ticket on the boat across the small glacial lake. The climb up the path, surrounded by conifers and with the water gently cascading beside me was precisely the soothing balm I’d sought for my agitated mind. For that hour or so, I released the anger I felt at the racism and xenophobia that had given rise to the injustice served against the Japanese Americans and that I saw was again threatening to unravel the thread of American decency and aspiration. My bile rises up again as I write this but for that hour, I allowed myself to simply be.

It didn’t matter that the falls, while lovely, were no more entrancing than Johnson Falls in Banff.

It wasn’t relevant that the path to Upper Inspiration Point was closed and that the ash had rendered the view from Lower Inspiration Point somewhat less than inspiring. The setting was quietly restoring some serenity.

It’s likely it was simply due to the name of the lake but as I sat on that rock I found myself quietly singing an old Harry Chapin song.

When I finally turned back down the path and started toward the boat dock, I realized that I’d fully released my agitation. That the ash limiting my views was unimportant because the DNA that drives my cells and the rocks uplifted by convection are all connected. All the molecules inside me, inside the trees and inside the rocks were born in the explosions of supernovas across this vast universe. All that had mattered for that hour was being present in the mountains, the trees, the sky, Cascade Creek, and Jenny Lake.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026