Heart Mountain heartless.

On Monday, 8 December 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt went before a joint session of Congress to seek a declaration of war. In his address, he called 7 December 1941, the day of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, “a date which will live in infamy.” Just more than two months later, on 19 February 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 making that day for many Japanese Americans, another “date which will live in infamy.”

[FDR signing a bill – from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

Here is the full text of that executive order:

Executive Order No. 9066

The President

Executive Order

Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas

Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense material, national-defense premises, and national-defense utilities as defined in Section 4, Act of April 20, 1918, 40 Stat. 533, as amended by the Act of November 30, 1940, 54 Stat. 1220, and the Act of August 21, 1941, 55 Stat. 655 (U.S.C., Title 50, Sec. 104);

Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders whom he may from time to time designate, whenever he or any designated Commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion. The Secretary of War is hereby authorized to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary, in the judgment of the Secretary of War or the said Military Commander, and until other arrangements are made, to accomplish the purpose of this order. The designation of military areas in any region or locality shall supersede designations of prohibited and restricted areas by the Attorney General under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, and shall supersede the responsibility and authority of the Attorney General under the said Proclamations in respect of such prohibited and restricted areas.

I hereby further authorize and direct the Secretary of War and the said Military Commanders to take such other steps as he or the appropriate Military Commander may deem advisable to enforce compliance with the restrictions applicable to each Military area here in above authorized to be designated, including the use of Federal troops and other Federal Agencies, with authority to accept assistance of state and local agencies.

I hereby further authorize and direct all Executive Departments, independent establishments and other Federal Agencies, to assist the Secretary of War or the said Military Commanders in carrying out this Executive Order, including the furnishing of medical aid, hospitalization, food, clothing, transportation, use of land, shelter, and other supplies, equipment, utilities, facilities, and services.

This order shall not be construed as modifying or limiting in any way the authority heretofore granted under Executive Order No. 8972, dated December 12, 1941, nor shall it be construed as limiting or modifying the duty and responsibility of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with respect to the investigation of alleged acts of sabotage or the duty and responsibility of the Attorney General and the Department of Justice under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, prescribing regulations for the conduct and control of alien enemies, except as such duty and responsibility is superseded by the designation of military areas here under.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The White House,

February 19, 1942.

A history of hate.

Although the order never specifies any ethnic group, with the stroke of his pen, Roosevelt effectively authorized the forced relocation and internment of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. The Heart Mountain camp near Cody, Wyoming, would become one of those confinement sites. That the order would be read as applying exclusively to Japanese Americans was unsurprising. Ethnic animosity toward Asians reached back for decades dating to the late nineteenth century.

For example, by law, the Issei, (Japanese Americans born in Japan) could not become American citizens. Long before the start of the Second World War, state legislatures passed laws that prevented the Issei from owning land, marrying American citizens, or working in certain jobs. For much of the twentieth century in California, Japanese students were required to attend segregated schools.

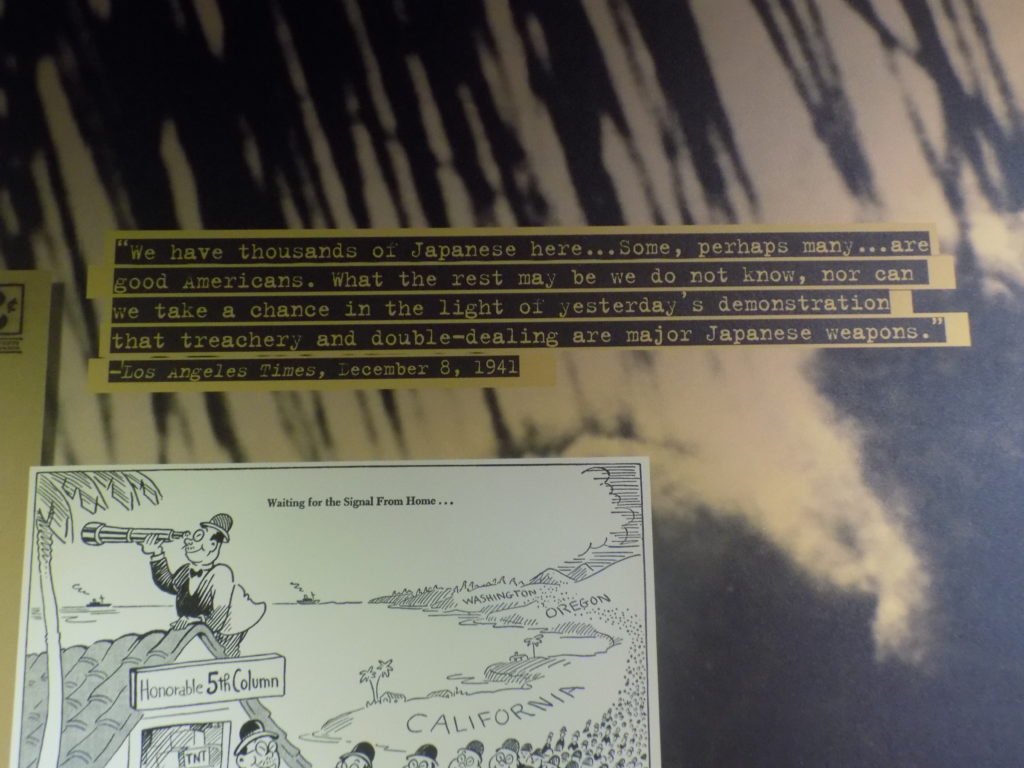

How rapid was the public reaction? I point you to the Los Angeles Times from 8 December:

(For those who don’t enlarge the photo, the text reads, “We have thousands of Japanese here… Some, perhaps many… are good Americans. What the rest may be we do not know, nor can we take a chance in the light of yesterday’s demonstration that treachery and double-dealing are major Japanese weapons.” Note: I don’t know what statements fill in the ellipses nor whether this was placed on exhibit after 16 June 2015.)

Draconian measures began within days of the attack. Japanese American community leaders were arrested based merely on the suspicion that they had ties to Japan. All the Issei saw their bank accounts frozen by the United States Treasury. A mandatory curfew was placed on Japanese Americans and, at least with regard to this group excluded from the protection of the Fourth Amendment, because their homes were subject to searches without a warrant.

Throughout the war, the U S government abetted by the media, generated an ongoing stream of anti-Japanese racially stereotyped propaganda. The Japanese, and by extension Japanese Americans, were portrayed as less than human and the derogatory terms “Nip” and “Jap” were in common use in film, radio and newspapers again beginning as early as 8 December.

“Only what we could carry.”

It’s no accident that I’ve used the title from Lawson Fusao Inada’s book as the heading for this subsection. In five short words it captures not only the experiences the Japanese in the U S faced at the outset of World War II but also the implication of how much they lost.

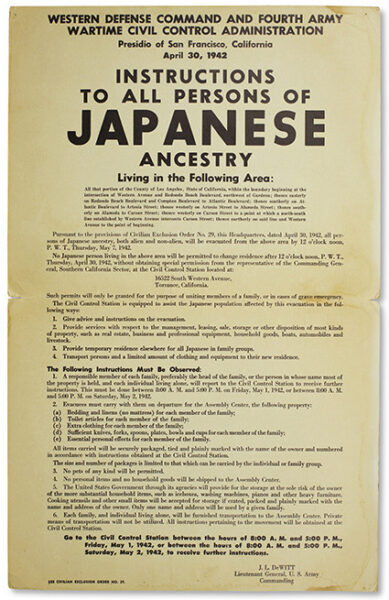

On 2 March 1942, mere weeks after Executive Order 9066, General John L DeWitt issued his set of “Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry” under the auspices of the War Relocation Authority.

[Image from Japanese American National Museum.]

This was the federal agency responsible for the evacuation, relocation, and internment of Japanese Americans and the construction and administration of internment camps throughout the United States. These orders, posted prominently throughout the Japanese American community, indicated where and when the Issei (first generation immigrants) and Nisei (children of Japanese descent born in the United States) were to report with their belongings.

Though initially voluntary, the order soon became mandatory forcing some 120,000 Japanese Americans and those of Japanese ancestry to move inland. Of course, much as they had been with the need to house prisoners of war, the federal government was unprepared for the mass removal of so many people from their homes and businesses. The Japanese were initially sent to one of 17 makeshift “assembly centers” often at fairgrounds or racetracks – places hardly fit for human habitation. Most of the Japanese who were incarcerated at Heart Mountain were first housed at Santa Anita Racetrack. They were held there for months while the government found sites and hastily constructed the ten internment camps for Japanese Americans. Like the other camps, Heart Mountain was selected for its relative isolation. It also met the same requirements as sites such as the P O W Camp in Douglas.

Rarely receiving more than a few days notice, each internee was allowed to carry a single suitcase. Businesses, farms, and homes were abandoned and ultimately lost to foreclosure. The “fortunate few” with enough time and foresight sold their property but at fire sale prices. Almost none of this lost property would be restored at the war’s end.

Because of the single suitcase limit, it wasn’t unusual to see men in their best suits or people wearing several layers of clothing. Normally, the people weren’t informed of the location or the length of their relocations. This National Archives photo shows a typical scene.

One might wonder why the Japanese cooperated in this mass relocation and internment. First, although no evidence of cooperation between the Issei and Nisei with the Japanese government or military was ever uncovered by either the FBI or military investigations, nearly all the leaders in the Japanese American community were arrested within days of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Second, the Japanese American Citizens League, founded in 1929 (now the oldest Asian American civil rights organization) became the de facto spokesperson for the community. They argued against the forced relocations before eventually urging the community to cooperate to prove their loyalty to the United States. Third, the Japanese had no real or practical means of fighting the power and authority of the U S government.

The story of Japanese internment, its aftermath, and my visit to the Heart Mountain Camp continues in part two.