A lot of afternoon remained so I knew I had time to wander around the city, find some more Mozart residences, take a photo of something unexpected in a city the size of Vienna, and visit another small museum while still having enough time to grab a light dinner before joining Ross and Andrea, and a few others from the Earthbound group to see Herbert Blomstedt lead the Vienna Philharmonic in concert at the Musikverein. This concert wasn’t on the Earthbound schedule but Ross was kind enough to navigate the ticket buying process for all who wanted the opportunity to hear a live performance at one of the most justifiably famous concert venues in Europe. It promised to be a grand day that I hoped more than scratched the surface of Vienna. Let’s get started.

Nailing it down – sorta.

My first stop was an easy one. I wanted to take a photo of a unique bit of Vienna that everyone in our group had walked past at least once almost certainly without noticing – the Stock im Eisen. (I was guilty of this, too, because I hadn’t pinpointed its location until I set out to photograph it. I’d return later in the day to get a less reflective picture than the first ones I took.) The Stock im Eisen is, as far as I could tell, the only remaining example in Vienna of the centuries old tradition of the nail tree.

Akin to the way people toss coins into fountains today hoping for good fortune, people in medieval Europe hammered nails into living trees. By the 18th century, the practice had become customary for traveling metalsmiths. Later, locksmiths carried on the tradition of the nagelbaum (nail tree) though no explanation – either factual or legendary – exists regarding their reason for doing so. By the 19th century, the tradition had ended.

The Stock im Eisen (Staff in Iron) at the corner of Kärntnerstraße and Graben is cited as the oldest preserved nail tree. It’s a spruce estimated to be more than 600 years old and arborists who examined the tree estimate that nails had been driven into it for about 40 years before it was felled in 1440. It’s name appears in a written document from 1533 and it’s been on display since 1548 when it stood at its present location at the corner of a small house. The current Palais Equitable replaced that dwelling in 1891 while preserving a piece of the tree.

From the nagelbaum to Museum Freud without a slip.

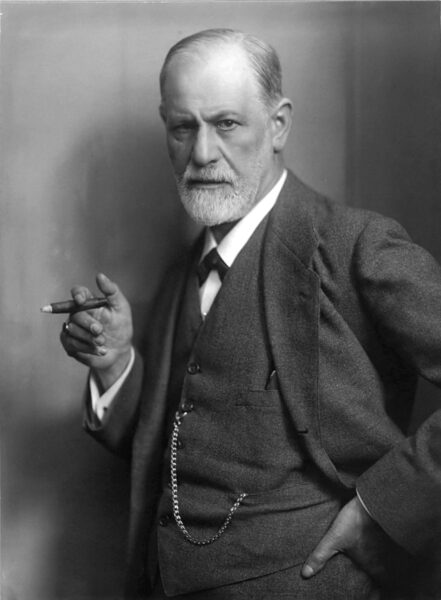

Unlike many of the other people I write about in this blog, I think Sigmund Freud is so well-known and has made such an indelible mark on western culture and medicine that a mere biographical sketch should be more than sufficient for most readers.

Freud was born to Jewish parents in what is today Příbor, Czechia on 6 May 1856 but his family moved to Vienna when Sigmund was just four years old. In 1873, he enrolled in the medical school at the University of Vienna where he concentrated in biology and spent six years researching physiology under the guidance of Ernst Brücke, director of the university’s physiology lab before specializing in neurology. He received his medical degree in 1881.

[Photo of Sigmund Freud from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

He spent several years working as a medical doctor at Vienna General Hospital then resigned in 1886 shortly after returning from a three-month fellowship in Paris where he’d gone to study with Jean-Martin Charcot. In the same year he married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of a prominent Hamburg rabbi. Although he was an atheist, Freud and Martha had both a civil and religious ceremony as required by Austrian law at the time.

In 1891, with two children already in tow and four more yet to come, the Freuds moved into the newly built house at Bergasse 19

the location of Vienna’s Freud Museum. By this time, at least partly inspired by his time with Charcot, Freud had a private practice treating psychological disorders. He’d adopted a method of talk therapy suggested by the work of a long-time friend and colleague Josef Breuer. Freud and Breuer jointly published Studies in Hysteria in 1895.

After splitting with Breuer, Freud published a seminal work The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900 and, following a lecture tour of the United States in 1909, he would publish his Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis in 1916. Freud continued to write prolifically until his death in London in 1939 just a year after being effectively exiled there after the Nazis’ Anschluss in 1938.

I can’t say with certainty that I gained any great or even new insight into Freud himself by my visit to his house and office but I learned he’d had a deep, ongoing correspondence with Alfred Einstein that began in 1932. Nearly 20 of those letters have survived.

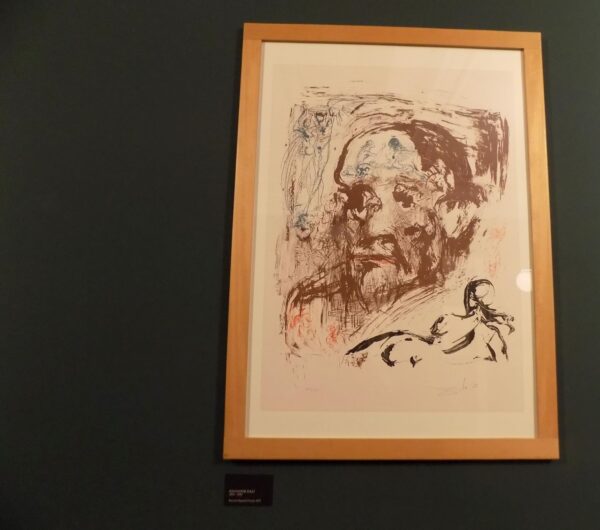

I also happened on an interesting twist of timing. Four or five days prior to my visit the museum opened a special six-month long exhibition called, “Surreal! Imagining New Realities” that their website described as, “100 works from the Klewan Collection by more than 50 artists and numerous writings highlight the tense relationship between Surrealism and psychoanalysis.”

One of those works is this portrait of Freud

by Salvador Dalí. Curiously, the Lower Belvedere was nearing the end of a five-month special exhibition called “Dalí-Freud An Obssession”. Their website noted, “The theories of Freud clearly fascinated Dalí, perhaps to the point of obsession.” The only time the two are known to have met happened shortly after the Freuds settled in London.

Weiner Musikverein.

Although it’s often ranked as the best orchestra in the world, in a blind taste test, I doubt I could tell you the difference between the Vienna Philharmonic which has its home at the Musikverein and the best American symphony orchestras. This would hold equally true for the great European orchestras and other concert halls as well. But, as someone who savors great orchestras playing great music, it would have been inconceivable (and yes, that word means what I think it means) to pass up the opportunity to attend a concert at the Musikverein let alone that orchestra in that hall. Here’s how it’s described on the Wikipedia page,

The acoustics of the building’s ‘Great Hall’ (Großer Saal) have earned it recognition alongside other prominent concert halls, such as the Konzerthaus in Berlin, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and Symphony Hall in Boston. With the exception of Boston’s Symphony Hall, none of these halls was built in the modern era with the application of architectural acoustics, and all share a long, tall and narrow shoebox shape.

About half our group decided to take in this concert and, as I noted above, Ross was kind enough to navigate the online ticketing maze and purchase tickets for most of us. Conducting the orchestra that night was the venerable (and since he was nearing age 95 I stress venerable) Herbert Blomstedt. That evening’s program featured Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms

(Muti’s interpretation is brighter and more allegro than I recall from that night.)

and the much longer and grander Mendelssohn Symphony Number 2 also called “Lobgesang”.

(Played here by the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Claudio Abbado.)

This was both a sensible and suitable pairing. Sensible because both call for a chorus and in combination require a bit less than two hours. Suitable because Blomstedt is noted for his interpretation of work by German and Austrian composers including Mendelssohn.

I can’t say how much rehearsal time the orchestra and chorus had spent with Blomstedt but their affection and respect for him was clear from the way they acknowledged him at the close. (The concert was Monday night and Blomstedt is a devout Seventh Day Adventist – a denomination that, like Judaism, celebrates its Sabbath on Friday night and Saturday. While Blomstedt will lead performances on Friday nights and Saturdays because he deems them an expression of his religious devotion, he won’t rehearse at those times because he considers rehearsing work.)

My notes from the evening cite the warmth and richness of the sound of both the orchestra and the hall and the excellence of the soloists. I also noted with some dismay the general age of the audience that you can see from all the white hair in the photo above.

In a mildly amusing coda, the orchestra presented each of the three solo vocalists (two sopranos and a tenor) with a large floral bouquet. They, in turn, presented all three to Blomstedt who, from our distance, looked as though he might topple over had he been required to carry them off stage. Fortunately, he did neither.

The hall was less than a kilometer from the hotel so we walked back most of the way together stopping at Eissalon Tuchlauben for ice cream before settling in for the night and preparing for tomorrow’s activities.

I think I figured it out. I’ll send you an email to cfoisoj@yahoo.com.

You did, indeed, solve the contest puzzle I put forth through other media. Congratulations. As soon as I have the necessary information, your prize is forthcoming.

To anyone else, second and third place prizes remain.