Glittering and littering.

a visit to Museu do Dinhero.

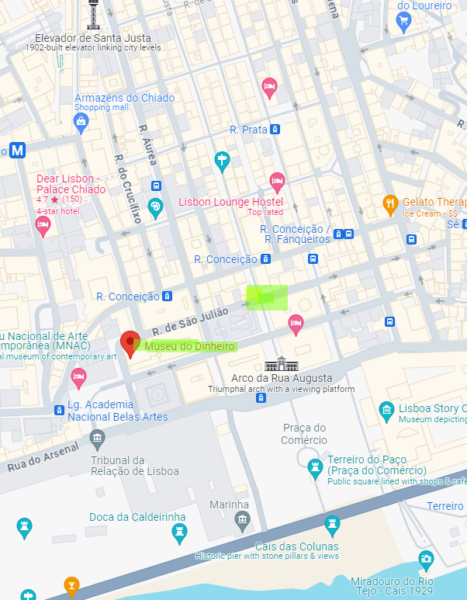

The last museum I visited in my two months in Lisboa – Museu do Dinhero – is one that’s quite close to my flat but one that I had, walked by on both my extended stays an uncounted number of times. (Many times. I don’t know how many times but certainly not countless times. The number might be large but it’s quite finite. Had I any inclination to count them, I certainly could have.) How close, you ask. About 650 meters from my flat this year and half that from my flat last year.

Curiously, one of my main motivators for entering this free museum operated by Banco de Portugal was to get out of the rain. On this day, I was trying to squeeze in one of my daily walks between rain showers but encountered a heavy downpour not far from the museum so I thought, “Well, this is a good time to see what this museum is all about.”

(The weather during my stay had an interesting pattern. For the first two weeks every day was glorious. Beginning in the third week when my company arrived, the weather was tolerable but with some chill, lots of clouds, and occasional rain. Once everyone left, the days again turned glorious – daily sun with temperatures warm enough for me to leave my sweatshirt in the flat. The last few days the skies opened often for hours without pause.)

Once I decided to visit the museum, it meant I’d be doing some previously unplanned research. The photo above isn’t from that day but I’ll start your tour by telling you a little about the building. If you think it looks more like a church than a museum, your perception is correct. It was originally the Church of São Julião but that church was not originally at this location. By now, the map of Baixa below should be at least vaguely familiar.

I’ve highlighted the church’s original location and the location of the museum. Another church, the Patriarchal Church of King João V, occupied the museum site before construction began on the Church of São Julião in the second half of the eighteenth century. Both churches were destroyed in the 1755 earthquake. Dom João V had died in 1750 and after the earthquake, his son, Dom José the First, essentially ceded control of the state to the Marquês de Pombal. The king showed no inclination to return to the center of Lisboa allowing Pombal’s plan for the city to include relocating São Julião to replace the patriarchal church.

However, the building’s troubles weren’t quite done. Construction on the new Church of São Julião was completed in 1810. Six years later, a fire destroyed much of the church and it underwent another reconstruction that lasted until 1854. At some point over the ensuing half century, the church ceased functioning in that capacity so in 1910, the Banco de Portugal began negotiating with the Archconfraternity of São Julião to purchase the church and its outbuildings. These negotiations lasted until 1933 when the bank acquired the deed for 10,000,000 escudos and the church was deconsecrated.

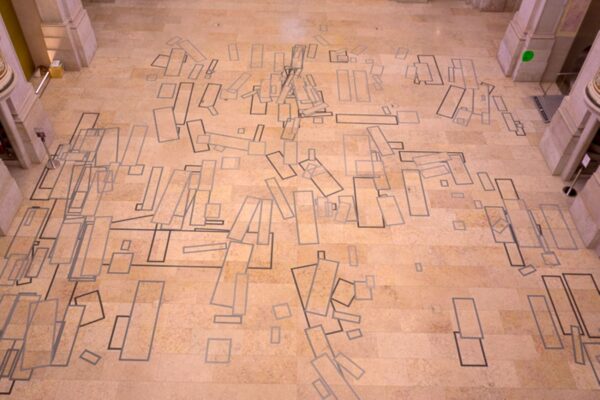

One interesting aspect of the building’s original use appears on a section of the floor.

These apparently random rectangular markings represent the locations of graves that were excavated during the Bank’s reconstruction to repurpose the building for its current use.

That clinking clanking sound can make the world go ’round.

I’ll start by noting that, although free, this museum has by far the tightest security of any I’d visited in Lisboa with a magnetometer so sensitive that my belt buckle sounded the alarm and I had to be wanded. Passing through security gains you admission to the building but not fully to the museum although there is a room where visitors can interact with Hermes – the Greek god of barter and trade. To see the rest of the museum, you must pass through this rather imposing entryway

where you receive a bar coded ticket to access some of the interactive features. In this area you can also look at and touch a gold bar valued at nearly a half million euros.

You proceed through the museum vertically from the first floor to the fourth before finally descending to an archaeological space preserving and providing detailed information about the section of the muralha do Dom Dinis (King Dinis’ Wall)

– the city’s medieval wall – that was, like the graves, uncovered during the Bank’s renovation of the space.

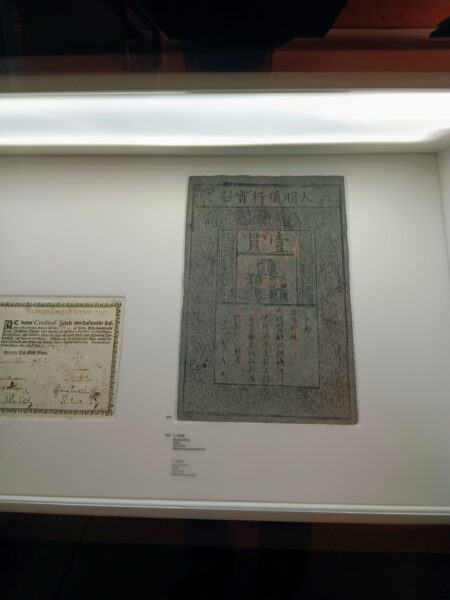

But that comes at the end of your visit so let’s return to the beginning and climb the stairs to the first floor. Here we start with displays detailing the origins of money as a replacement for the direct exchanges of goods. You can see some of the earliest coins

both originals and reproductions – and the first paper money from Europe (Sweden) and an early Chinese note.

Continuing the ascent, we climb to the space the museum’s website calls “The Treasure Room.” Here, “A forest of tubes encloses and gives voice to the most representative pieces of the collection. Rare items tell bits of stories, of episodes immortalised (sic) on the faces of coins minted in the Hellenic world or in the territory of the Iberian Peninsula.”

Farther on, we learn how the Portuguese explorations of the 15th and 16th centuries influenced the development of money and monetary systems. As we progress through the museum, we follow the history of money through various eras of Portuguese history. I focused on the period beginning in the First Republic through the Estado Novo and finally to Portugal’s integration with the Euro.

The top floor brings us to the present day. The content focuses on the production of money and the steps taken to limit forgery not only with the euro but with bank notes from around the world. In all, it’s quite an interesting journey.

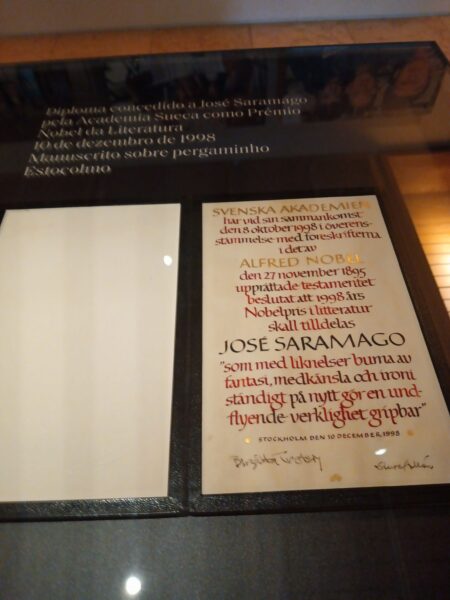

Finally, in addition to the fascinating archaeological information presented along the exposed portion of King Dinis’ wall (The display includes unearthed pottery, animal bones, and other remnants of historical life.) showing how archaeologists use it to decipher historical events and derive clues about daily life spanning the 700 year history of the wall, there’s one final bonus –

The diploma issued to José Saramago – Portugal’s Nobel Laureate in Literature.

While you’re waiting for my final post or two, you can look at some additional photos here.