Because I was feeling rested after lunch and since my 75 meter morning climb hadn’t been enough of a challenge, and based on the review on Atlas Obscura, I decided to hike up to the Museu da Farmácia (Pharmacy Museum). The museum was just a bit over a kilometer distant and the route would take me mainly up rua Garrett and entail a 50 meter ascent.

I’d pass some familiar sights along the way – the statue of the famed poet Fernando Pessoa

inviting you to join him for a bica outside A Brasileira; the nearby statue of António Ribeiro

also known as Chiado (from whom the neighborhood might take its name); and along the Praça Luís de Camões where I’d taken this photo of the big Christmas Ball last night. (Don’t be fooled by those heavy coats. The temperature was probably about 14° C. I guess that’s chilly for Lisboetas.)

While I found the walk worthwhile in terms of exercise, I wasn’t particularly impressed with the museum. Here’s the AO write-up:

MUSEU DA FARMÁCIA OPENED ITS doors in 1996 in Lisbon with the mission of preserving the tradition of the pharmaceutical profession in Portugal. The collection eventually grew in scope to embrace different pharmaceutical traditions from across the globe.

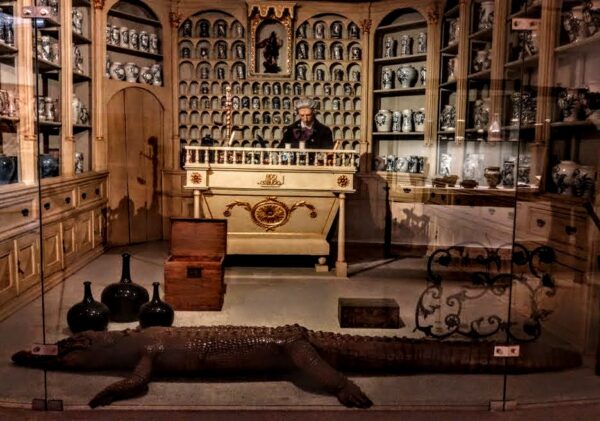

Most of the items showcasing the pharmaceutical tradition in Portugal were donated by individual pharmacies through the Direção da Associação Nacional das Farmácias, the body that regulates pharmacies in Portugal. The larger items on display are entire apothecaries from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. These installations include a wide array of instruments utilized in the profession, such as scales, weights, mortars, pestles, and containers of all sizes and shapes. Arguably, the most interesting items from the old Portuguese apothecaries include stuffed crocodiles, cobras, and pufferfish, jars of pickled seahorses, and vials filled with colorful liquid and fibrous substances.

The upper floor of the museum is dedicated to international pharmaceutical traditions, with items from Europe, Mesopotamia, Latin America, and the Far East. On display are healing statuettes, decorated leather condoms, ominous chastity belts, and illustrated textbooks. The interwoven nature of culture and medicine speaks volumes in this section.

However, not all the artifacts on display are from the distant past. More recent items include the portable pharmacy that was used on the Russian Mir Orbital Station, and the one that was taken on the Space Shuttle Endeavour on its final launch in 2000.

If you’re wondering about the crocodile they mention, this picture should rock your world.

Perhaps I would have found the museum more to my liking had I either been fluent in Portuguese or had I written down the impossibly long WiFi password and downloaded the app that I presume had English explanations of many of the displays and artifacts that had only Portuguese text in the physical place. There was some English but most of the time I was unsure not only of the historical or pharmacological importance of what I was seeing but simply what it was I was seeing. Perhaps, had I not arrogantly assumed that everything would have English explanations, I wouldn’t be writing that this was the most disappointing Atlas Obscura suggestion I’ve visited.

(I also learned later from Ana that the museum’s restaurant that has outdoor seating and a lovely view of the Tejo also serves some of the tastiest and most inventive petiscos {small plates} in Lisbon.)

As I returned to the flat for another rest before dinner, I passed this statue on the Praça do Municipio.

It’s call Paréidolie. The phenomenon of pareidolia that Wikipedia defines as, “the tendency for perception to impose a meaningful interpretation on a nebulous stimulus, usually visual, so that one sees an object, pattern, or meaning where there is none.” is something I’ve discussed when writing about some of my other trips. Often, one needs to look closely to discern the pattern and sometimes the pattern can be interpreted as more than one thing. What fascinated me about this particular object is that, despite the gaps and spaces, I can’t visualize this as anything other than a human face. Perhaps you can. (Update 2024: When I returned in December 2023, this art was no longer in that place. Since three works that weren’t there in 2022 adorned Terreiro do Paço, I have to assume that Lisboa has a program that rotates public art.)

Through streets broad and narrow.

Since I enjoy finding not only offbeat places to visit but unusual places to eat as well, I started watching YouTube clips of some of Anthony Bourdain’s global culinary adventures. So it was that I added Sol y Pesca to my list of places to eat in Lisboa. (Even if I know I’m not going to visit every place on them, I always leave home with a list of places to see and places to eat.)

Sol y Pesca is on the Pink Street and when you first encounter it it looks like a dive – perhaps a holdover from the area’s seedier days or from further back in its own history when the space sold bait, tackle, and other fishing gear. Look inside and you see

shelves of tinned fish. The contents of these cans of fish and seafood, served mainly in the form of petiscos, will constitute your meal. (In a different sort of carryout, you can also buy cans to take with you when your meal is done.)

So how did this Portuguese love affair with canned fish (especially sardines) arise? Let’s take a brief look.

Given its long coastline and abundant ocean fish, it’s not surprising that fish preservation has a long history in Portugal. You might recall that in the spring while driving from Tavira to Lisboa I stopped at the Roman ruins at Creiro that was a Roman fish salting complex from the first century. However, the canning process we use today was invented in France in 1810 when Nicolas Appert published his method of conservation using hermetic glass jars in the book “The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years”.

The process reached Portugal in 1853 when Ramirez opened the country’s first commercial cannery. Today, it’s the oldest fábrica de conservas (cannery) in Europe.

Perhaps surprisingly, the fish canning industry has experienced something of a boom and bust cycle. By 1925, less than 75 years after Ramirez opened its first factory, Portugal had nearly 400 canneries and that number continued to burgeon during the First and Second World Wars as both the Allies and the Axis displayed a voracious hunger for the product. At present, that number has dwindled to between 20 and 30 but automation allows for substantial production.

Although the sardine is clearly the king of Portuguese canned fish, it’s far from the only canned fish available. (Believe it or not, canned sardines are even healthier than fresh ones. Both are high in protein and vitamin B12 but the canned version has ten times more calcium because the jellification process breaks down the bones and makes them readily digestible.) You can easily find squid, cuttlefish, octopus, blue mussels, razor clams, codfish, Atlantic pomfret, horse mackerel, chub mackerel, Atlantic bonito, albacore, European eel, and one (hinted at above) that I had to try.

Using standard canning methods, the various kinds of fish are tinned with spices such as piri-piri peppers, fennel seed, fresh ginger, olive oil, water, and herbs. Some canneries use lesser-known ancestral methods such as fumagem (salting and smoking fish) and escabeche (preserving fish in vinegar).

After World War II and the 1974 Carnation Revolution, canned fish fell out of favor as an epicurean mainstay becoming instead a product viewed as one for the working class, students, and the poor. It might also have found its way onto pantry shelves as a shortcut to a meal. Interest in the conservas revived somewhat in the nineties although the primary market at the time was international. Then, Portugal’s first tourism boom in the early 2010s boosted the public popularity of canned fish products.

The video below provides some history and shows a more traditional production method quite different from the one used at Ramirez seen in the video above.

As for me, I did my best to duplicate Bourdain’s meal of smoked tuna, sardines on Pão Alentejano (a Portuguese sourdough bread), and tuna roe with sweet potatoes and horse mackerel. I also had a Super Bock beer that simply reinforced my preference for Sagres.

Oh, and that bit of canned seafood I had to try is referenced in the section header (If you don’t recognize the song, I’ll reveal it in the music post.) and that I’ll make part of my New Year’s Eve dinner is the humble cockle.

Interesting information on the canning industry in Lisboa. Not really a fan of tinned seafood in general except albacore of course.

Until you come to Portugal. We’ll get you to think differently. How’s the song contest coming along?

Interesting that none of the workers in either factory wear gloves or face masks when handling the food. That would never fly in the USA, but I doubt that anyone has ever been sick from eating it:) Really interesting, the difference between the two factories, but also the similarities regarding their workforce.

Agreed. I also found the arc of tinned fish popularity interesting.