The tour ended in the Cour Napoléon, we tipped our guide, and standing at the edge of the Tuilleries Garden on a beautiful – if somewhat warm – Sunday afternoon Pat and I decided that if we were going to visit a museum it should be one where we could stay outside so we set off for the Musée Rodin (Rodin Museum) in Paris. (Rodin has two museums in France – one in Paris and the other in Meudon, the town where he died, a suburb about four kilometers southwest of Paris. Meudon was an eight or nine kilometer walk from the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and the the museum on rue de Varenne was a mere three kilometers – actually closer to two had we chosen the shortest route.)

On our way, we passed by but chose not to visit, les Invalides. Originally built to serve as a hospital and home for war veterans, it has expanded to include museums and monuments all of which relate to the military history of France. The most prominent building in the complex is the one with the golden dome that has appeared (often in the distance) in several of my photos, the Dôme des Invalides. This large church contains the tombs of some of France’s war heroes including, most notably, Napoléon Bonaparte. Here’s a view of it poking above the sculpture garden of the Rodin Museum.

(The chapel was built between 1677 and 1706 during the reign of Louis XIV. At the time of the Revolution, it was called the Temple du Mars and became a military pantheon during the rule of Napoléon Bonaparte who honored two great French Marshals – Turenne and Vauban – with a tomb for the former and a mausoleum containing the heart of the latter.

Napoléon died on the island of Saint Helena in May 1821 and was initially buried there. In 1840, Louis-Philippe {the Citizen King} had Bonaparte’s remains exhumed with a plan to transfer them to the Dôme des Invalides. However, his plan was derailed during the Revolution of 1848 when Louis abdicated and the Second Republic was established. Napoléon III would affect a coup d’état in 1851 and eventually be declared Emperor of France. It was under his rule that the remains of his uncle were finally placed in the Dôme.)

RODIN.

François Auguste René Rodin, more commonly simply called Auguste Rodin was born in Paris on 12 November 1840 somewhere in the fifth arrondissment. His father, Jean-Baptiste, earned a modest salary as a clerk working for the police department. (Please don’t think that his name rhymes with the pterosaur from the 1956 Japanese movie. Even if you can’t reproduce the uvular trill that begins his name think of the last syllable as rhyming with ‘hat’ and hint at just a trace of the final ‘n’.)

After spending his earliest years as an indifferent student at a boarding school in Beauvais – about 80 kilometers east of Rouen – Rodin returned home at age 14 to attend the École Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathematiques more commonly called la Petite École (Little School) that trained boys in math and decorative arts. (The title Petite École differentiated it from the Grande École des Beaux-Arts that taught fine arts.)

Rodin studied at the Little School for three years before he made the first of his three applications to the Grande École. He was rejected each time and, given the perspective of history, the reason behind those rejections becomes ironic. Although he passed the drawing competition each year, the man who would come to be thought of as the father of modern sculpture failed the sculpture competition.

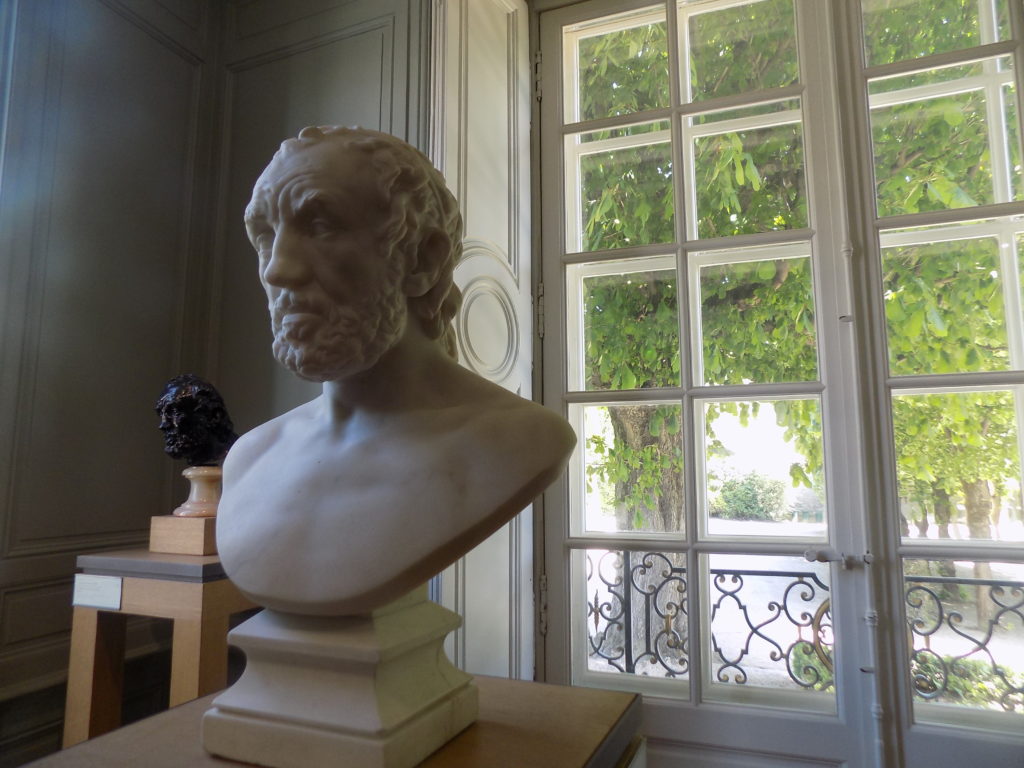

After the third rejection, Rodin resigned himself, at the ripe old age of 19, to seeking his living elsewhere. He took jobs in plaster workshops creating architectural ornaments. Although the steady work kept him from utter poverty, the young man found his life neither financially nor artistically satisfying. Like many determined artists, however, he didn’t allow the rejections by the Academie deter him from continuing to create sculptures. In 1863 he submitted a portrait bust, The Man with the Broken Nose, to the Paris Salon. The hidebound traditionalists on the jury rejected it (though they would accept it 10 years later) just as they did the paintings that went on to be displayed at the Salon de Refusés that same year. You can see the original bust in the background of the photo below with a marble copy carved by Léon Fourquet in the foreground.

In the mid 1860’s Rodin began a job filling commissions in the workshop of a commercial sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse. This improved his income if not his artistic standing or satisfaction. He toiled along until the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in which he served as an officer until the French surrender in 1871.

The first controversy.

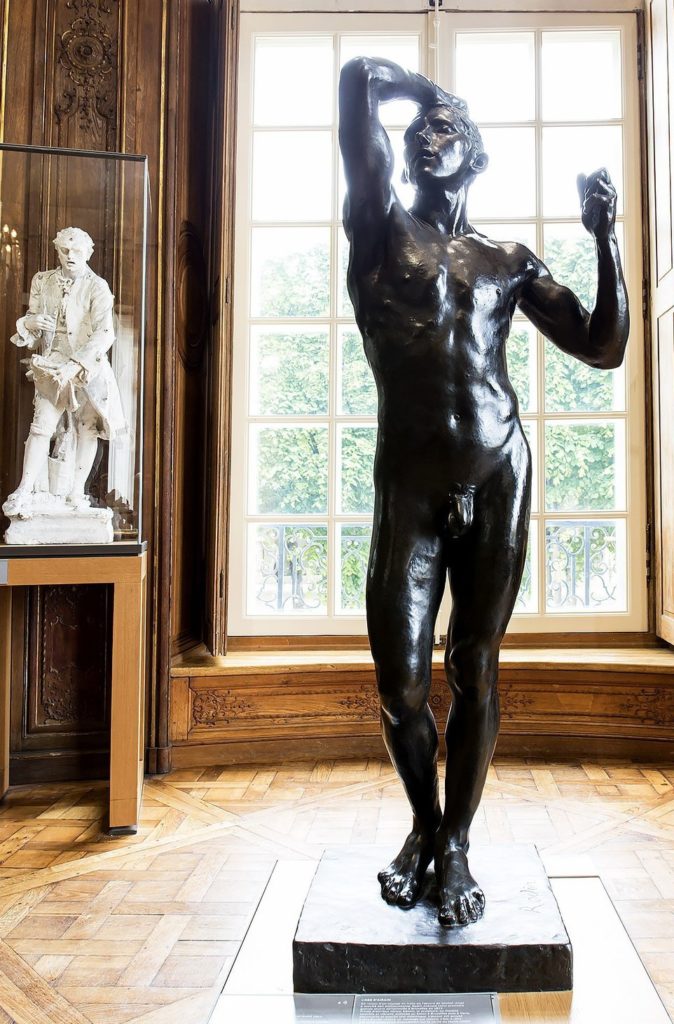

When the war ended, he continued his professional association with Carrier-Belleuse and relocated with him to Brussels in 1871. It was there in 1875 that he would have his career changing moment when he created a sculpture called L’Âge d’airain (The Age of Bronze). The Salon of 1877 accepted the exceptionally lifelike 183 centimeter tall work. Rodin’s depiction was so realistic that accusations arose accusing him of taking his cast directly from the model’s body and the resulting controversy might have been of equal importance to the arc of his career.

(Though most existing castings are in Europe, you can see it in locations around the world from Japan to Mexico. There are at least three in Paris and a dozen in the United States.)

Rodin, of course, denied the allegation but reveled somewhat in the attention the speculation drew. It was then that he decided to return to Paris with his longtime lover Rose Beuret.

Rodin had met Beuret in 1866 and she soon thereafter gave birth to a child she named Auguste-Eugene. The child kept the surname Beuret because Rodin would never legally claim patrimony. Despite his persistent infidelities, at least one of which was exceptionally passionate, Beuret remained his partner until the artist’s death in 1917. (The couple finally married in January 1917. Rose died two weeks after the ceremony and Auguste died in November of the same year.

Coming up, a look at that exceptionally passionate infidelity and embark on a rather superficial trip through the sculptor’s art.