Tourist spelunking.

The previous entry provided some dramatic views of mature Karst landscapes but peer below the surface and you may well find complex underground drainage systems forming karst aquifers. The surface can also hide caves or even extensive cavern systems. Recall that I pointed out a large karst in the United States that includes western Kentucky. If you have traveled there you might be familiar with the system called Mammoth Cave. Well, here in Slovenia, we’re about to visit another spectacular cave system – Postojna.

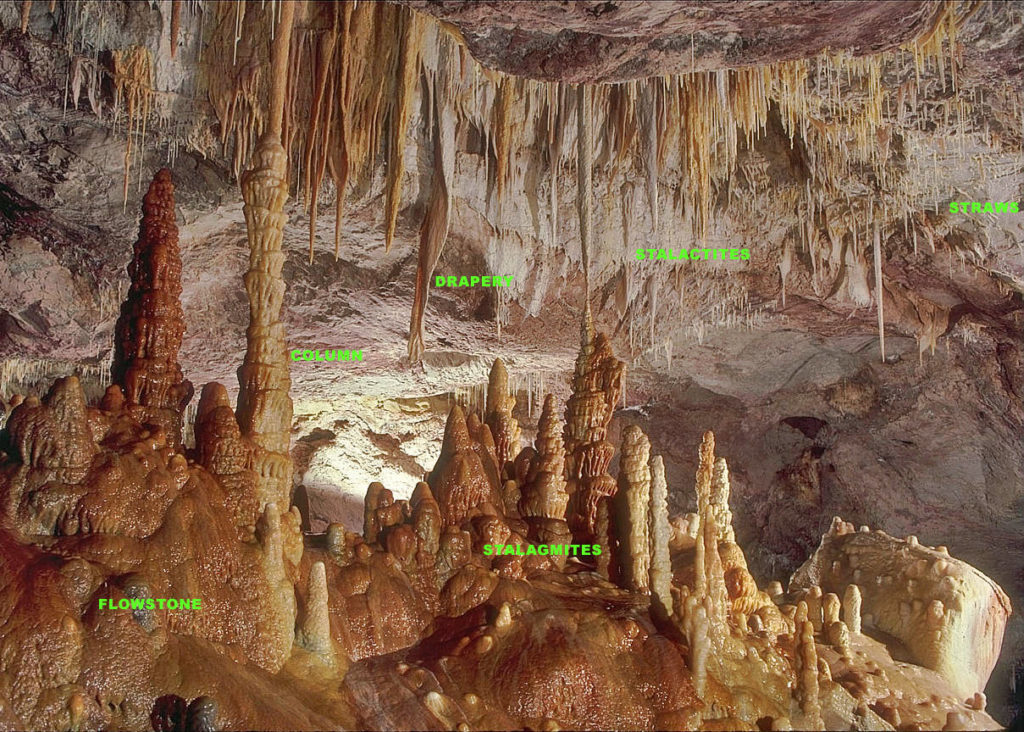

Before we get there, I want to introduce you to some of the types of speleothems that make visiting these karst caves such a grand experience. When rain falls, it brings with it through the air, molecules of carbon dioxide. When the water is slightly acidic as it is in a karst, it combines with the C O2 to form carbonic acid. This passes through the soil picking up more C O2 along the way weakening the acid but still leaving it strong enough to dissolve calcium carbonate (Ca C O3). The secondary mineral deposit that forms in the cave is a speleothem. The six common types of speleothems are identified in this photo by Dave Bunnell:

The Postojna cave system is more than 24 kilometers long and was hollowed out by one of those disappearing and reappearing streams I mentioned in another post, the Pivka River. (We’ll encounter the Plvka again in Ljubljana where it will be called the Ljubljanica River. Along the way it will also be known as the Unica River. Recall that karst rivers flow along the surface then disappear below it. When they reappear, they’re often taken to be a different river.) When we visit Postojna, we’ll have the opportunity to see about five kilometers of the two-million-year-old cave riding a train for about three fifths of the journey. After that, you can walk on your own or with a guide. The first cave train was installed in 1872 and was pushed by cave guides. Later the trains converted to gas engines that were then replaced by electric trains after the Second World War.

The cave was discovered in the 17th century and became something of a tourist attraction when Archduke Ferdinand visited in 1819. It’s noteworthy that electric lighting was added in 1884 which predated the reach of this convenience in the capital, Ljubljana by several years.

Rather than inundate you with downloaded photos, I’ll provide this rather slickly produced three-minute video noting that it ends with shots of Predjama Castle which we didn’t visit.

Of course, if you’re interested in seeing still photos, you can easily find them using your preferred search-engine.

Next stop Ljubljana.

Although it’s by far the largest city in Slovenia, Ljubljana, with a population of about 289,000 and an area slightly smaller than Washington, DC, the Slovenian capital is by no means a large city. Our time there was unique compared to the other stops on this trip. We had our usual guided walking tour on the afternoon we arrived, had some time on our own both that day and the following one after our visit to Lake Bled, and again time to explore on our own after a wonderful, guided music walking tour that Pat and Geannie had discovered on our third day there. For some in our group, the tour would end in Ljubljana. A few of us, however, would go on to spend three days in Budapest. Because our time in Ljubljana was more fragmented than it had been elsewhere, rather than adhering to the chronology, I’ll be conflating the time to best suit my narrative.

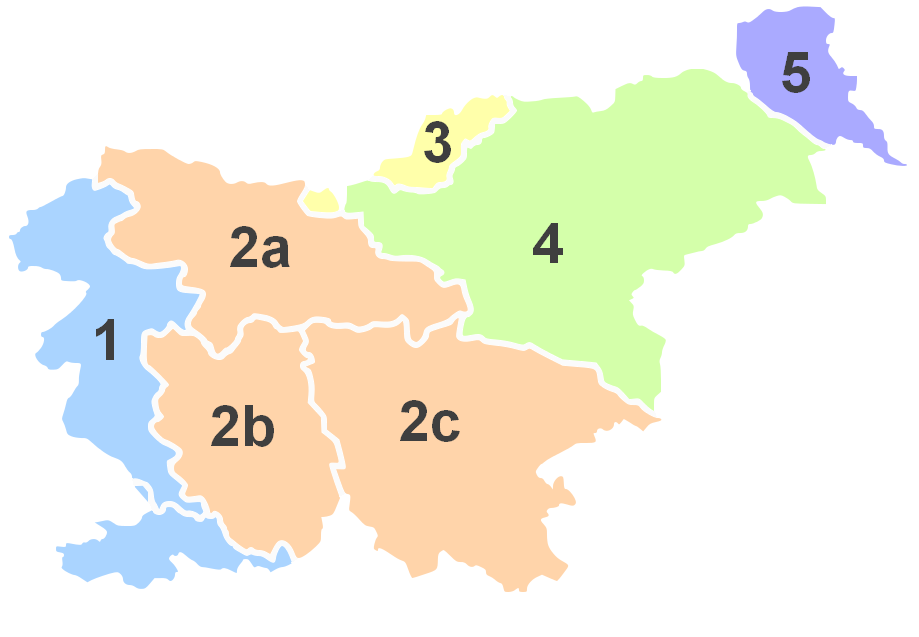

Long before it was the capital of Slovenia, Ljubljana was the capital of Carniola (Slovene: Kranjska) one of the five traditional regions within today’s Slovenia. Traditionally, Carniola was divided into three sub regions – Upper Carniola, Inner Carniola, and Lower Carniola seen on this Wikipedia map as 2a, 2b and 2c respectively.

(The other areas are {1} Slovenian Littoral; {3} Carinthia; {4} Styria; and {5} Prekmurje).

Slavic people first settled in the area in the sixth century after the fall of the Roman Empire. Other than a brief five-year period when Napoleon ruled the area from 1809-1814, Carniola was ruled by the Habsburgs from 1335 to 1918. The Austrians renamed the city Laibach.

However, when the area was considered part of the Illyrian Provinces of France under Napoleon, Ljubljana became the capital of not only Carniola but of a much broader stretch of territory that included most of present-day Slovenia, the Istrian Peninsula and stretched along the Adriatic as far south as Dubrovnik.

In this brief five-year period, Ljubljana prospered and grew both physically and intellectually. The French founded a university there in 1810 that, although it was disbanded in 1813, when Austria regained control, reorganized the former Austrian schools into the ecoles centrales that are now considered the charter of the University of Ljubljana. During their brief rule the French regime also established the first botanic garden at the city’s edge, redesigned the streets, and made vaccination of children obligatory.

Perhaps even more important to the Slovenes, much as Alexander II had done in Finland, Napoleon not only allowed the local population to use its Slovenian native language but also built a course of education in elementary and secondary schools allowing the use of the provincial Slovene language in Slovenian areas. In fact, much in the way that Helsinki has a monument to Alexander II, there is in Ljubljana, a French Revolution Square with a monument to Napoleon.

In 1895 an earthquake measuring 6.1 on the Richter scale rattled the city and destroyed about 10 percent of its buildings. The rebuilding period spanned about 15 years from 1896-1910 and, during this time, which is called the “revival of Ljubljana,” the city underwent a number of important changes. Architecturally, many areas were rebuilt in a style known as the Viennese Secession that, because it took its inspiration from Art Nouveau, altered the look of the city. Administratively, electric lighting came in 1898 and urban administration, health, education, and tourism all saw progressive reforms.

Now that you know some of the history we learned on our tour, it’s time for me to backtrack a bit to our lovely and, as always, centrally located hotel. The Hotel Union is just a block from the main city square – Prešeren Square. In Pat’s picture below, we are leaving the hotel to meet our guide for our usual walking first day tour. The pink building on the right is the Franciscan Church of the Annunciation or, as the locals call it, the Franciscan Church. The tour begins in the next post.