Any 21st century visitor to the Sydney suburb called The Rocks would likely find its name a bit puzzling because there are few rocks apparent as you can see in this aerial view provided by Airview to The Dictionary of Sydney.

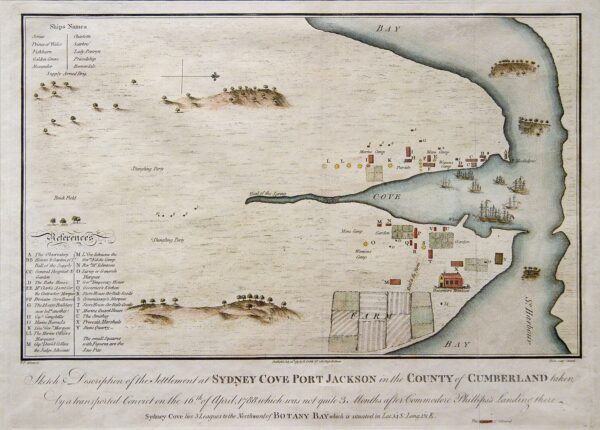

Even this early 1788 Francis Fowkes representation of Sydney Cove (called Warrane by the Gadigal People)

[Wikipedia – Public Domain]

fails to depict the area’s rocky western peninsula and its rugged topography that inspired the convicts who arrived on the First Fleet to christen it with that moniker.

Soon after the first ships arrived at Botany Bay, Arthur Phillip, the first governor of New South Wales (a name chosen by Captain Cook to distinguish it as British and to counter any Dutch claims to the territory) realized that, despite the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks, the site wasn’t appropriate for settlement because it had poor soil, limited building materials, no reliable water source, and no secure anchorage. After some additional coastal exploration, he chose Port Jackson at Sydney Harbour as the area for the first settlement.

Frankly, it made some sense for him to establish his colony of convicts and guards there. The┬Ā Wianamatta Shale and Hawkesbury Sandstone on the rocky outcrops made the area well suited for settlement in one important way. They provided convenient materials for building construction. Additionally, the smooth surfaces could facilitate some degree of sanitation by allowing rain to wash away waste.

His second in command, Captain John Hunter, opined that the tolerable land, “…may be cultivated without waiting for its being cleared of wood; for the trees stand very wide of one another, and have no underwood…” Of course, Hunter misunderstood two important factors. First, the trees were well adapted to growing in the relatively unfertile soil and, perhaps more importantly, he knew nothing of the way the Indigenous People shaped the landscape through carefully managed controlled burning that promoted the growth of grasses and isolated the big trees. Whereas the infertility of the soil to European agricultural plants would soon force the settlers farther inland to Paramatta,

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

Phillip established the colony in Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788.

Although they lacked the appropriate skills, the convicts were nearly immediately set to constructing buildings out of the local sandstone on the relatively more orderly eastern side of the harbor for the governor, guards, and other civil staff while they settled on the western side. The area’s rugged terrain made construction of orderly streets all but impossible leading to a web of winding footpaths. These factors reinforced the sobriquet.

As you can see from the aerial photo above, the area is surrounded by water on three sides and for most of its history the legitimate businesses were seafaring, waterside workers and the maritime trades. However, with its winding and uneven streets, it remained a convicts’ place into the middle of the nineteenth century and was a place where, as one writer described it, “every species of Debauchery and villainy is practiced.”

The Rocks would house Sydney’s first jail which was built of wood in 1797 and, after a fire destroyed it, rebuilt in 1799 using sandstone. If one extends the definition of the Rocks to include Circular Quay, the area could claim the settlement’s first hospital which was built in 1788.

The Rocks was also the site of Sydney’s original town center. The public wharf at First Fleet Park and George Street became the de facto town marketplace. The 1842 painting below by Henry Allport depicts how the market may have appeared even though a new market some two kilometers to the south was well-established.

[From Rocks Discovery Museum – Library of NSW]

Change is gonna come

Although the transportation of convicts from Britain continued until 1840, by the beginning of the nineteenth century they were being sent to other parts of the colony and more reputable colonists were arriving. Still, in 1823 most of the area’s residents were emancipated convicts or convicts and their children. During that decade, however, expanding trade began to bring some changes to the neighborhood.

A stone store built on Argyle Street in 1826 served as the first Customs House for the merchants and ship owners using the port. It’s still used today.

Then came 1851 – the year of the gold rushes. They began when a prospector named Edward Hargraves discovered gold at Ophir near the town of Orange about 250 kilometers west of Sydney. There were other finds in Sofala and Bungonia in New South Wales and several finds in the colony of Victoria. These gold rushes brought waves of immigrants not all seeking gold and even fewer doing so successfully. Over time, as the Dictionary of Sydney describes it, “The Rocks became a place where immigrant people found their first foothold, squeezed into existing houses and even converted stables.”

As the convict labor supply dwindled, work on projects that had begun in the 1840s such as street making, paving, and drainage slowed just as the demands of rapid urban growth increased the need. Although some of the wealthier merchants had built houses near their businesses creating an element of class diversity, the rapidly multiplying maze of lanes and blind courts created severe problems of water supply, rubbish, and sewage disposal.

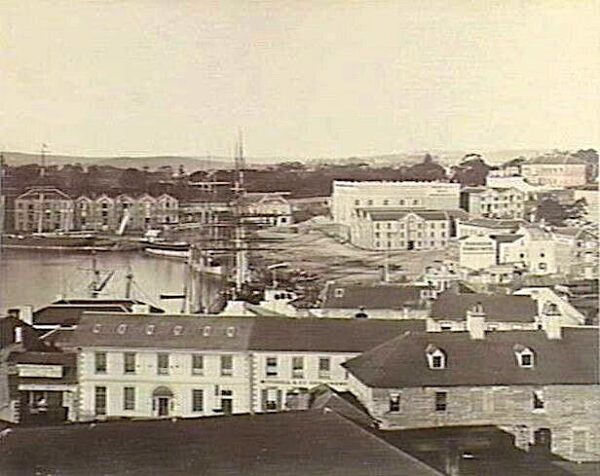

More change came to The Rocks in the latter part of nineteenth century as wealthy and upper middle class people migrated to more distant suburbs. It became a more hardscrabble, working class, and immigrant neighborhood. Coupled with its proximity to the waterside and its links to Australia’s convict past – links that were becoming more problematic especially to convict descendants – The Rocks became an increasingly disreputable area. The image below from the 1870s is looking toward Circular Quay.

[Image from Historical Australian Towns]

Unsurprisingly, Sydney’s growing prosperity didn’t reach many of its poorer neighborhoods and The Rocks was among them. The infamous Push Gangs added to its image of a rough area with an abundance of pubs frequented by gamblers and prostitutes who plied their trades among immigrant workers and merchant seamen.

By 1900, much of the area had come under government ownership and many of its buildings – from warehouses, to shops, pubs, and housing such as the one shown below built around 1810 –

[From The Rocks Discovery Museum]

were among the more than 800 buildings demolished to make space for the construction of the Harbour Bridge.

The Battle for the Rocks

(You’re gonna need a heart of steel.)

In 1970 the local government established the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA). Their plan would have replaced The Rocks with “high-rise office towers, retail and commercial space, luxury hotels and apartments, and underground car parks.” filled with housing that, because it would have been unaffordable, would have, without consultation displaced all, or nearly all the residents at that time. Rumors of impending evictions led Nita McRae

[From The Rocks Discovery Museum]

to form the The Rocks Resident Action Group (RRAG). They would eventually develop a plan to safeguard The Rocks as a residential and historically significant area.

When a year of governmental lobbying attempts failed, she enlisted the support of the NSW Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) who imposed perhaps the world’s first green ban on The Rocks in 1971. Led principally by Jack Mundey, the notion of a green ban held that workers had the right to refuse labor if they deemed it would be used in harmful ways.

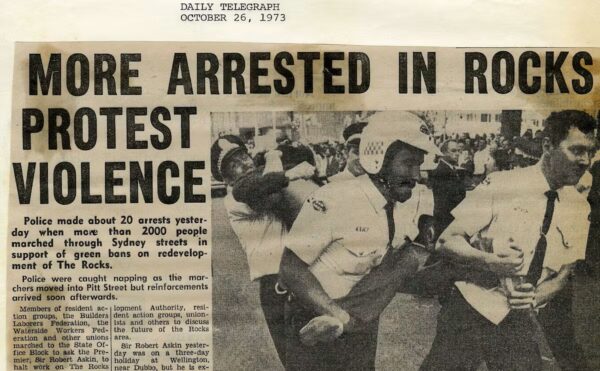

This set off clashes between developers and politicians on one side and labor unions and neighborhood residents on the other culminating in a week of protests that began on 18 October 1973.

[From The Rocks Discovery Museum]

Despite a series of press misrepresentations and even attempts to bribe the union leaders, the resistance remained unshaken. This adamant intransigence brought support from other unions and the broader public and the SCRA eventually capitulated. The residents and the BLF developed an alternative plan that succeeded in safeguarding their homes and heritage.

Rather ironically, the one high rise building known as Sirius, that was built to originally serve as public housing was sold to developers in 2019. The redevelopment of the iconic brutalist building displaced many long time residents who were generally elderly and underprivileged.┬Ā If you’re interested in learning more details about The Battle for The Rocks, you can read about it here.

In the next entry, you’ll meet one of my fellow travelers and join us on a lengthy walk through Sydney on our lone free day in Australia’s largest (or second largest) city. There you’ll also find a link to more photos from the day.

Thanks Todd. Wonderful summary of history and development.

Comment #7 for the month! Thanks. It’s good to know someone is reading and that I seem to be getting it right.