My third day in Australia got off to an interesting start when my phone rang at 02:45. Although this call was one worth taking, it reminded me of the time difference to the US and going forward I turned on my phone’s Do Not Disturb feature before retiring each night. The call was from Road Scholar and informed me that they would be paying for one night of the two nights I’d be in Auckland before joining that group tour. I note this because it likely impacted my experience of the first of this day’s three activities RS had planned – a trip to the Taronga Zoo.

When I travel, whether on my on or as part of a group tour, I constantly strive to find a balance of experiencing a place or activity (being in the moment), observation (looking for the details), absorbing information (learning), and documentation (photos and notes). I may not always achieve it but it’s always worth the effort. Something I can’t do contemporaneously is synthesize those four facets into a cohesive whole. To do this, I need to take several days or even weeks beyond a trip’s end.

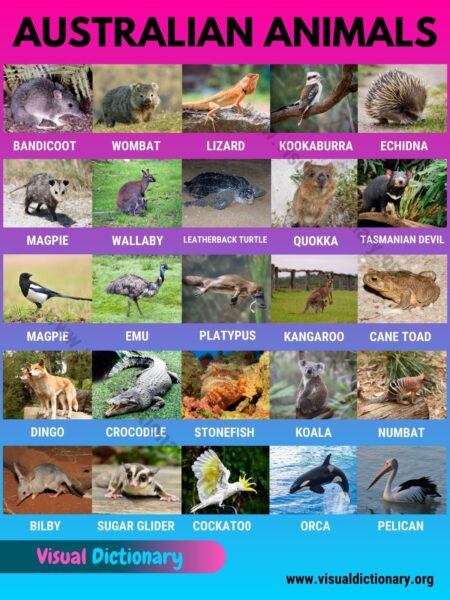

Australia’s high rate of endemism (an estimated 3,000 species of vertebrates alone) certainly makes its fauna worth exploring.

[From Visual Dictionary (did you spot the mistake?)]

Since seeing many of these animals in their native habitats is excessively time-consuming at best and probably often unlikely, a trip to a zoo is a sensible option and perhaps more engaging than a lecture might be. Additionally, it got us out and moving about and into the sunlight both of which are good things.

(I’ll be your one Your one and only.)

Sydney’s first zoo opened in 1884 in a place called Billy Goat Swamp in Moore Park about 10 kilometers from its present location at Bradley’s Head – which you’ve seen in previous posts in maps of Sydney Harbour – and where it’s been since its opening in 1916. Behind its impressive entry building

sit 28 hectares (an area 25% larger than its original 21) with eight specific sections. My recollection is that, although our group split into two with each volunteer zoo guide having her own Whisperer. I think both groups remained primarily in the area called Nura Diya (words from the Cammeraigal People that have been gifted to the zoo. Similarly the name Taronga is from the same language meaning either “shoulder” or “sea-view” with both translations being appropriate given the zoo’s location.

An essential element of Taronga Zoo’s conservation efforts has been its successful breeding programs for endangered species both on and off the continent. One example of the zoo’s role internationally is its successful breeding of 44 red pandas (natives of southeast Asia) over the past half century.

On the home front, the zoo has already reintroduced 15 chuditch or western quolls into the wild. They’ve had similar success with the regent honeyeater and both southern and northern corroboree frogs.

We started our walk with a peek at this fellow:

This is a tree kangaroo. Yes, kangaroos have adapted to live in trees or perhaps it’s more accurate to say they’ve readapted. Go back far enough in time and you’ll discover that all macropods (the family that includes kangaroos, wallabies, wallaroos, and quokkas) were once tree dwellers. Much like hominids, these macropods descended from the trees to exist more terrestrially. The ancestors of today’s tree kangaroos returned to the trees. Found primarily in the rainforests of northern Queensland, they are the largest tree-dwelling mammals in Australia.

On our walk we also encountered wallabies, kangaroos, emus, koalas and a sleeping (non-baby eating) dingo.

![]()

At the end of our walk, the groups reunited for a presentation from an enthusiastic zookeeper who gave us the opportunity to see a funnel-web spider – a black arachnid about which Wikipedia notes, “The bites of the Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus) and northern tree-dwelling funnel-web spider (Hadronyche formidabilis) are potentially deadly…” Even though the spider was in a plastic box, I think she believed simply seeing one of Australia’s deadly creatures was enough so she next brought us a sleepy blue-tongued lizard called a shingleback skink. There are four subspecies of shingleback. Three live in the state of Western Australia while the fourth lives in the east. All are endemic to Australia.

Our final guest was this fellow

(and I know he’s a fellow because we were told he’s been busily impregnating females). He’s an echidna. Also endemic to Australia, one obvious reason echidnas are fascinating is because they’re monotremes or egg-laying mammals. (The only known existing monotremes are four species of echidna and the platypus which sadly we didn’t see.) Echidnas mainly eat termites and ants but will dine on earthworms, beetles, and moth larvae in a pinch. But it isn’t their diet that’s noteworthy, it’s the way they find and consume their prey. Echidnas use both a finely developed sense of smell and their beaks are sensitive to electrical stimuli emanating from the ground below. They are toothless so they have to grind their food between their tongues and the bottom of their mouths. The beak of a short-billed echidna such as the one seen in this photo ranges from 6 to 7.5 centimeters long.

Our demonstration ended here because, for the first but not the last time, RS had other plans for us and we had to trundle off to the bus. But before we travel back across the city to our next stop, I need to briefly bring to your attention another aspect of Country that’s central to the lives of Australia’s first people.

I am Country

You might (or might not) recall from the post a beautiful city and a brilliant people, I wrote, “Before the arrival of the First Fleet, the Gadigal people had custody of the land they called Tallawoladah.” This is because the area around the harbor was Gadigal Country. However in writing about Taronga, I talked about it being the land of the Cammeraigal People. By boat it’s barely five kilometers from Tallawoladah to Taronga. It’s likely that these were different clans or bands. As the Sydney Barani site notes,

There are about 29 clan groups of the Sydney metropolitan area, referred to collectively as the Eora Nation. There has been extensive debate about which group or nation these 29 clans belong to. It is generally acknowledged that the Eora are the coastal people of the Sydney area, with the Dharug (Darug) people occupying the inland area from Parramatta to the Blue Mountains. The Dharawal people’s lands are mostly confined to the area south of Botany Bay, extending as far south as the Nowra area, across to the Georges River in Sydney’s west.

Clans or bands (called ‘tribes’ by the Europeans) within Sydney belonged to several major language groups, often with coastal and inland dialects.

There is some disagreement as to the degree of cultural separateness of the people who traditionally lived in the adjoining lands which comprise greater Sydney, encompassing most of the western suburbs and stretching up to the Blue Mountains.

However, there is much evidence to suggest that the major language groups of greater Sydney were different groups using different languages and different initiation rites. There is evidence of Aboriginal people migrating in a north-south direction but none from east to west. The appearance of men from the inland group was different from that of coastal men who were missing their right incisor tooth, removed during their initiation.

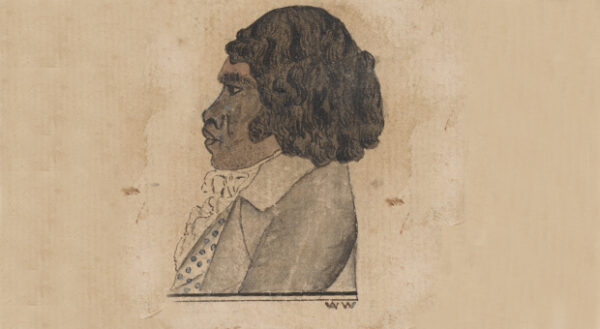

Similarly, when Bennelong of the Wangal people went into Parramatta in 1789, he did not understand the language spoken there so that’s another practical example of clans being distinct entities. The 29 clan groups of the wider Sydney region were associated with specific areas of land by family boundaries, and distinguished by body decorations, hairstyles, songs and dances, tools and weapons.

[A portrait of Bennelong c1793 attributed to the artist George Charles Jenner Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW – DGB 10]

[From Sydney Barani]

These different languages and initiation rites were likely critical in defining a band’s Country and the size of a clan’s country was, in some part, dependent on the availability of resources. Well-managed prior to the European usurpation, these smaller areas likely provided sufficient resources for clans to survive and thrive according to their traditions. One central element of those traditions are that the clan in any Country believed that they were the land and the land was them; that they had been charged by the creators with caring for the land as they would care for themselves and that other clans both neighboring and distant had the same responsibilities to their land. Encroaching on another band’s Country without the appropriate welcome and permission was, with few exceptions, not conceivable within the worldview of Australia’s First People.

As alien as this concept may be to the western mind, you need to keep it in your thoughts as you read this journal. It will aid your understanding of the continent’s First People – something these photos are unlikely to do – though I hope you’ll enjoy them.