The past is always present.

While Paraguay has little impact on the world or even regional stage in the 21st century, at one time it was a regional power. Its history as an independent nation begins when Captains Pedro Juan Caballero and Fulgencio Yegros led a militia that deposed the governor appointed by the Argentine led Viceroyalty of the RĂo de la Plata. They declared Paraguay’s independence on 14 May 1811 although it wouldn’t gain international recognition until 1842.

Although the military had expelled the Argentinians, a lawyer working behind the scenes became the de facto dictator of the country for the ensuing three decades. JosĂ© Gaspar RodrĂguez de Francia y Velasco declared his official title as “Supreme and Perpetual Dictator of Paraguay” and was called El Supremo by the general population.

[Painting of JosĂ© Gaspar RodrĂguez de Francia y Velasco from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

While keeping Paraguay mostly isolated from outsiders, RodrĂguez de Francia sought not only to break the power of the Catholic church but to create a social structure inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 1762 book The Social Contract. He attempted to create a mestizo society by prohibiting colonial citizens from marrying one another and allowing them to marry only mulattoes, blacks, or people from the indigenous GuaranĂ. (He succeeded to a significant degree. While few traces of GuaranĂ culture remain beyond the language, even today more than 90 percent of Paraguayans consider themselves mestizos.)

There was a brief power struggle after El Supremo died in 1840. It lasted until 1844 when Carlos Antonio LĂłpez secured the seat of power. The elder LĂłpez ruled for nearly two decades and was succeeded by his son Francisco Solano-LĂłpez in 1862. Despite their attempts to portray the country as democratic, the LĂłpez family controlled nearly every aspect of life in Paraguay. They began by abolishing slavery in 1844.

[Francisco Solano-Lopez – Photo from Wikipedia – Public Domain.[

However, even with a rigidly centralized economy, the country was generally prosperous (though with clear divisions of class) and, with the assistance of several hundred foreign engineers and technocrats, rapidly expanded its steel, textile, paper and ink, naval construction, weapons, and gunpowder industries. In fact, the noted British judge Sir Robert Phillimore described Paraguay in the middle of the 19th century as, “the most advanced Republic in South America.”

Now we need to turn our attention slightly to the south and east. Until its independence was settled by the Treaty of Montevideo in 1830, the country of Uruguay was the subject of nearly perpetual conflict between Brazil and Argentina. After its independence, it was beset by nearly perpetual civil war. A treaty settling the internecine conflict known as the Platine War gave Brazil, which had supported the winning side, the right to intervene in Uruguay’s internal affairs.

When, in 1864, Brazil announced its intention to exercise those rights (which it had done periodically since 1851), Solano LĂłpez, thinking he could thrust himself into diplomatic stardom by forcing the Brazilians and Uruguayans into treaty talks that he would oversee, overestimated both the real and perceived strength of his military declaring that Paraguay wouldn’t stand for Brazilian troops occupying Uruguayan land. Brazil’s emperor, Pedro II,

[Painting of Pedro II from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

ignored Solano-LĂłpez’s bellicosity and, as was his right by treaty, invaded Uruguay. Solano LĂłpez responded not merely by declaring war on Brazil but by attacking the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso and sending uninvited troops through Argentina to Uruguay. Not surprisingly, the Brazilian-backed side won the war in Uruguay and the governments of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina signed a secret agreement to annex half of Paraguay’s territory, collect reparations, forbid it from keeping an army, and to fight together until they had removed Solano-LĂłpez from power.

This led to the War of the Triple Alliance or, as it’s known in Paraguay, the Great War.

Devastation down the decades.

Superficially, it appears rather remarkable that despite being surrounded by three hostile powers and having a dearth of sufficient weaponry, the Paraguayans fought for four years stalemating the Argentinians in the swamplands along that border and blocking a water borne Brazilian advance with water mines and obstacles at the fort of Humaitá on the Paraguay River. A deeper look shows the price the nation paid for the stubborn truculence of Solano-López.

To begin, he drafted every man in Paraguay, leaving little labor to work the fields. Crops began to rot and starvation set in among the general populace. Men and women succumbed to cholera, malaria, and dysentery. As able-bodied men died, Solano-LĂłpez built an army of child soldiers clothing them in oversized red army uniforms, arming them with sticks painted to look like guns, and disguising them with fake beards. The uniforms dwindled to rags and eventually the children fought naked. (Today, Paraguay celebrates Children’s Day on 16 August – the anniversary of a battle in which at least 2,000 children perished.)

The Great War not only cost Paraguay nearly half its previous territory but it essentially depopulated the country. According to Thomas Whigham of the University of Georgia, as many as 90% of Paraguayan men died from combat, disease, or starvation – a fate suffered by 60% of the general population. Whigham’s figures are on the high end Other researchers calculate a lower mortality rate, the number remains shockingly high and could be considered, as one Paraguayan diplomat called it, Paraguay’s holocaust.

Some demographers estimate that by the end of the war Paraguay’s population was a mere 228,000 with men accounting for only 28,000 of that number. To survive, the country needed to repopulate but despite the government’s decidedly pro-immigration policies, records indicate that an insignificant 12,000 immigrants, mainly from Europe and the Middle East, passed through the port of entry at AsunciĂłn between 1882 and 1907.

(This shot of the countryside taken from the bus provides some idea of the scenery.)

Because of the population imbalance in the time between the end of the Great War and the early 20th century, women headed most households in Paraguay. Additionally, with so few men available, the women casually paired off with itinerant men using the justification that they needed to repopulate the country.

This behavior, along with other factors, established a tradition of promiscuity in Paraguay where sexual intercourse in public places was common though not commonly approved and often of questionable motive. One newspaper of the time wrote, “Men without modesty may be found even in the corridors of the Church and the cemetery, atrociously scandalizing even during the day to satiate their brutal passions.” And, according to a 2012 article in The Economist, “No one knows whether the intercourse in ‘plazas, streets and meeting places’ was rape, prostitution or a result of the privileges men enjoyed because of the distorted sex ratio.”

That same article quotes BenjamĂn Fernández Bogado, a Paraguayan reporter as saying, “Having children in huge quantities wasn’t a problem. Even priests could have children.” Bogado was likely speaking in reference to Paraguay’s one time president Fernando Lugo.

Lugo, a Roman Catholic priest and bishop, was elected president in 2008 and by early 2009 at least three women had come forward asserting that Lugo had fathered their children – though two of them appeared to have been conceived after he left the Church to run for political office. (I’ll have more about Lugo in an upcoming post.)

The Gran Chaco War.

In 1969, Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong asked, “War, huh, good god, What is it good for?” and answered, “Absolutely nothing.” For an already depopulated country like Paraguay, the answer could almost be less than nothing. Thus, in 1932, when Paraguay, whose population still languished at 1,200,000 again found itself at war with one of its neighbors – in this instance Bolivia – its efforts to repopulate were again stymied.

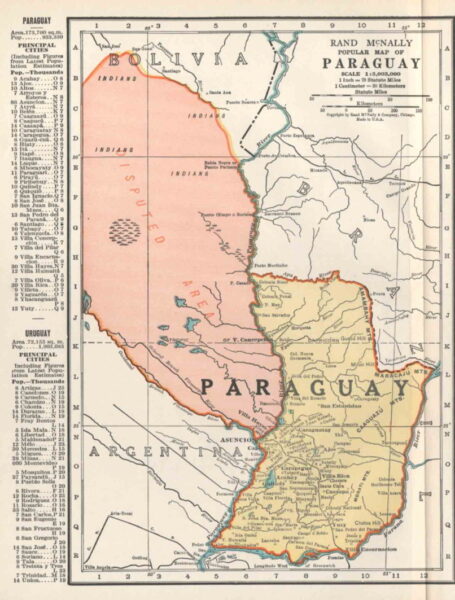

I’ll discuss the War of the Pacific between Bolivia, Chile, and Peru in a later post but this 19th-century conflict sowed some of the seeds of the Chaco War when Bolivia lost approximately 400 kilometers of coastline and became landlocked. Some say that when the 1929 Treaty of Lima ended any Bolivian hopes of regaining a land corridor to the Pacific, the government sought to gain control of the Paraguay River which flows through the Chaco, joins with the Paraná, and would provide an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean.

[Map from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

Other sources will assert that when oil was discovered on the northern Andean plains, two competing oil giants, Standard Oil backing Bolivia and Royal Dutch Shell supporting Paraguay, each seeking the rights to explore and exploit the southern plains goaded the two governments into a belligerent state. Whatever the cause, the war lasted three years until June 1935. With more than 56,000 Bolivian fatalities and 38,000 Paraguayans killed, it’s considered the bloodiest military conflict fought in South America during the 20th century. While the country held on to two-thirds of the disputed territory, Paraguay had to recover from yet another war.

Since tomorrow will be another travel day (though not an entirely uneventful one), I’ll break here. Coming up, a bit more 20th and 21st century Paraguayan history and a little closer look a its capital city AsunciĂłn where we spent the night.