I shortened the previous post promising a serious discussion followed by my walk with the three women around the city’s walls.

First, the Jews.

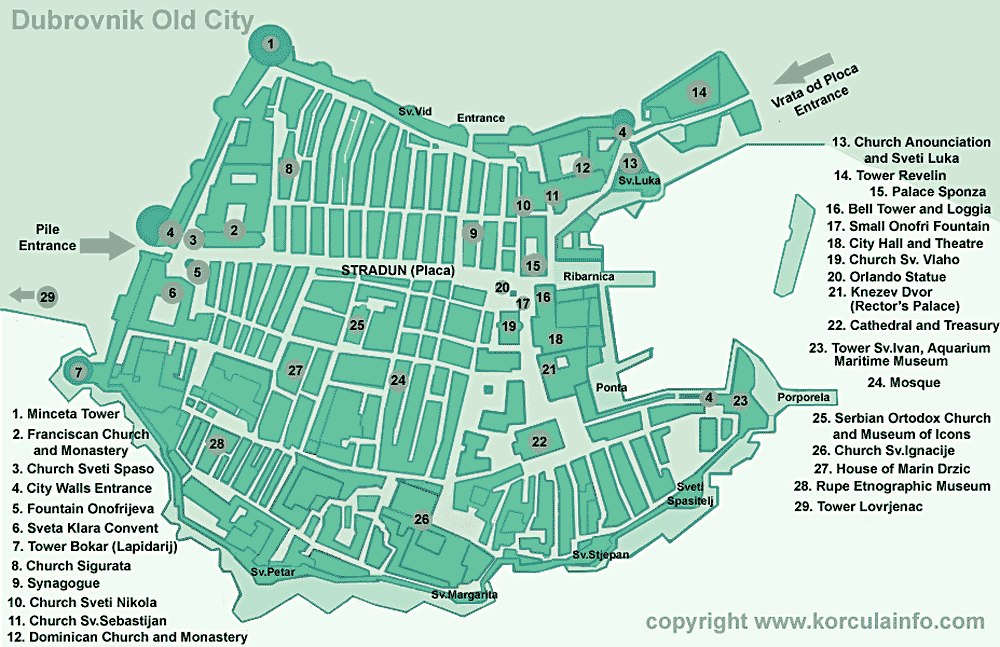

Dubrovnik occupies a strategically important spot – particularly for traders plying the Adriatic and Mediterranean. A look at the map below, reveals the synagogue in the Jewish Quarter (9) that’s more a street than a quarter but is just two blocks from the trading center at Sponza Castle (15):.

Jews have had a long, albeit small, presence in Dubrovnik. The first written record appears in 1326. A ruling by the Dubrovnik Senate in 1407 allowed Jews to settle in the city. Within a year, they had established a synagogue that is the oldest active Sephardic synagogue in the world and the second oldest synagogue in Europe. It’s noteworthy that, until that time, the authorities had permitted only Catholicism to be officially observed in the city. The existence of this synagogue, however, is more a confirmation of the importance of Jews in maritime trading than a real sense of generosity or inclusion by the Ragusans. A door to the Jewish Quarter was locked nightly and the Jews had to use a separate “Jews Only” tap at the Small Onofrio’s Fountain.

The Jewish population grew after the 1492 expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Though they generally thrived and fared much better than in other European nations, as they have wherever they settled in Christendom, the Jews of Dubrovnik suffered a number of periodic persecutions including an expulsion in 1515 but Jews returned to the area in 1532.

By the middle of the 18th century, Jews accounted for 238 citizens in a population of about 6,000. They lost their status of legal equality when the region came under the rule of the Austrian Empire in 1815 and the population shrank to just 87 at the outbreak of World War II. Of those, 27 died either as members of Tito’s Partisans or as Holocaust victims. Today the official Jewish population is 44 but 19 of them reside in the United States.

If you’re looking for it while walking along the Stradun, you’ll see this sign

meaning Jewish Street. Turn into the narrow street and there it is on your left.

Climb the stairs, pay the fee, and you can enter the second oldest Synagogue in Europe:.

Although the synagogue survived the 1667 earthquake, it suffered serious damage to its roof after being hit twice during the shelling of Dubrovnik in 1991.

Then, the war.

When you travel to the Balkans today, shadows of the 1991-1995 wars darken many places you visit and, in some places, you still hear echoes – both literal and figurative – of the conflict. In other places, rays of light and the tenacity of the human spirit shine through. I will touch upon both. Although I won’t delve into the causes of the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the ethno-religious wars that followed at this time, I must write a bit about Dubrovnik and the war.

Because it had received designation in 1979 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, many people believed, even after the onset of hostilities, that the Old Town would be spared any significant shelling. On the other hand, probably because of its UNESCO designation and the investment in its restoration, the Old Town is, in some ways, among the gentler places to be exposed to the horrors of that time.

By June 1991, both Slovenia and Croatia had declared their independence based on earlier referenda and in accord with the terms set forth in the Constitution of 1974. On 1 October 1991, the Yugoslav National Army or JNA (comprised mainly of Serbs and Montenegrins) began an assault on the Croatian coast shelling Mount Srd as early as October second. By the end of the month, they had succeeded in capturing significant territory but not Dubrovnik itself.

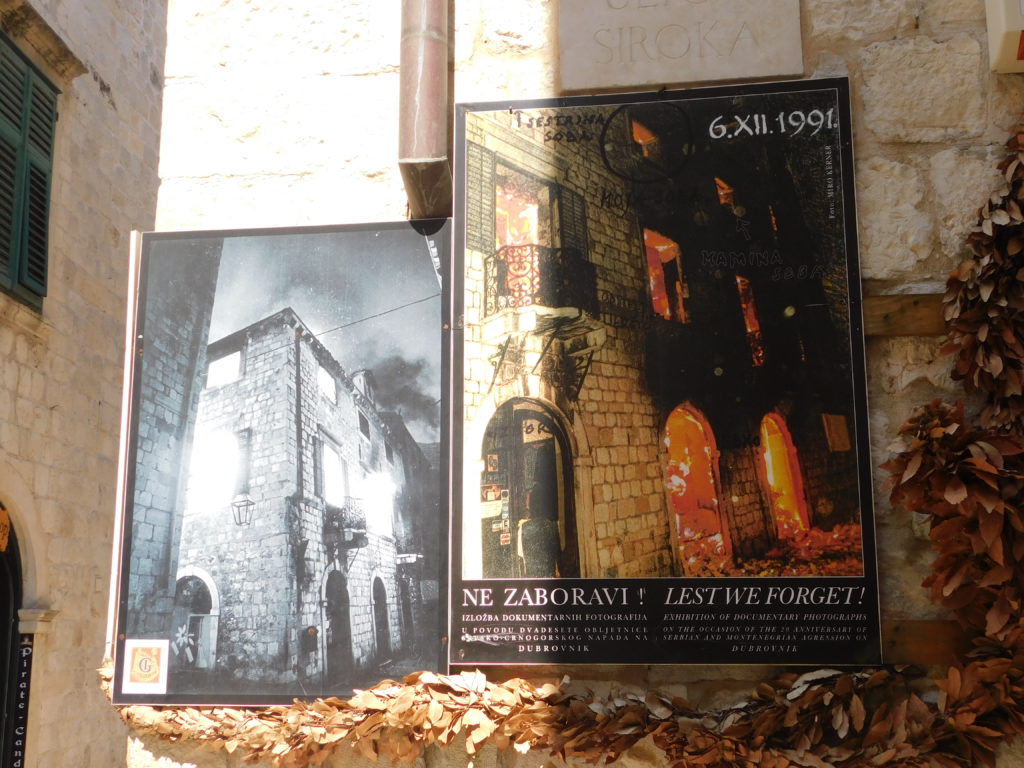

The city was under siege. Near daily bombings began on 23 October culminating with an intense bombardment on 6 December – a day that became known as the Saint Nicholas bombings. The northwest part of the city – including the Franciscan Monastery – received some of the most severe damage. Although the death toll among both civilians and military for the entire battle was relatively small – totaling 417 in all area military operations – 94 people died between October and December with 13 civilian deaths occurring on 6 December alone. Here’s one way the date is remembered:.

Here again is a photo of Big Onofrio’s Fountain.

Recall that it’s just inside the Pile Gate and only a few meters from the Franciscan Monastery. Amid a small photo gallery in the Rector’s Palace, I found this photo of the fountain from December 1991:.

By one estimate, of the 824 buildings in the old town, 68% were struck by shells, more than 11 percent were heavily damaged, and one percent burned beyond repair. Dubrovnik’s walls sustained 111 direct hits with another 314 on Dubrovnik’s baroque buildings and marble streets. Very little of this is visible today because tens of millions of dollars have been spent on restoration efforts. Some scars, deliberately left in place remain, but they are few and while the war is clearly remembered it’s not always clearly visible.

It’s important to note that one effect of the aggression by the JNA on Dubrovnik was that, although the Croatians were far from blameless, it helped shift international opinion to viewing Serbia as the clear aggressor and contributed to a growing economic and diplomatic isolation of the two republics sometimes called Rump Yugoslavia. The bombardment of Dubrovnik likely prompted the European Economic Community to agree on 17 December 1991 to recognize Croatian Independence which they formally did on 14 January 1992.

Climbing the Walls (and some other stuff).

What would a day in Dubrovnik be without a walk around at least a portion of the city’s famous walls? Why, it would be like a day without sunshine – and there was plenty of that the day we visited.

At the end of our stop at the Maritime Museum, Diane, Judy, Pat, and I began the trek that would take us halfway around the city walls. The walls follow the natural terrain so we were almost always walking up or down. During the walk, one of our principal tasks, as Diane reminded us, was to find her a ‘Kodak-ee moment.’ Diane lives in Fort Worth and, loudly affecting a heavier Texas accent than she normally had, described the reaction of some of her friends and family to her decision to visit the Balkans and Dubrovnik in particular. “Wah would you wanna go there? Ain’t that the place with the urnge roofs?” Urnge, of course is an important color in Texas with “burnt urnge” (orange), being the color of the University of Texas at Austin’s athletic teams.

Some of the views, while dramatic, were simply not dramatic or Kodak-ee enough for Diane. Eventually, however, we found a few that satisfied her aesthetic. Here are two that I shot that might be in the Kodak-ee ballpark:.

If you look closely at the roof tiles you might notice that they appear to be uniform and brightly colored. While it’s less obvious, the faded tiles on the building in the lower left of the second picture are not uniform. This difference marks one way of spotting buildings that had roof damage in 1991. In an interesting bit of trivia from our guide, we learned that while they are all of equal length, the older tiles were hand-fashioned but the curvature, shaped around the individual maker’s thighs, means they are not of equal width. Newer tiles are machine-made and of identical dimensions.

Before reaching the end of our day in Dubrovnik, I have three photos and one brief story to share. I took the first while traversing the city walls. It needs little explanation other than that I found the subject of a pigeon apparently seeking shade mildly amusing:.

The second is a photo I took in the Maritime Museum because a Todd’s trip journal without a photo like this seems somehow shallow and empty:.

Not a terrapin but a turtle nonetheless. GO TERPS!

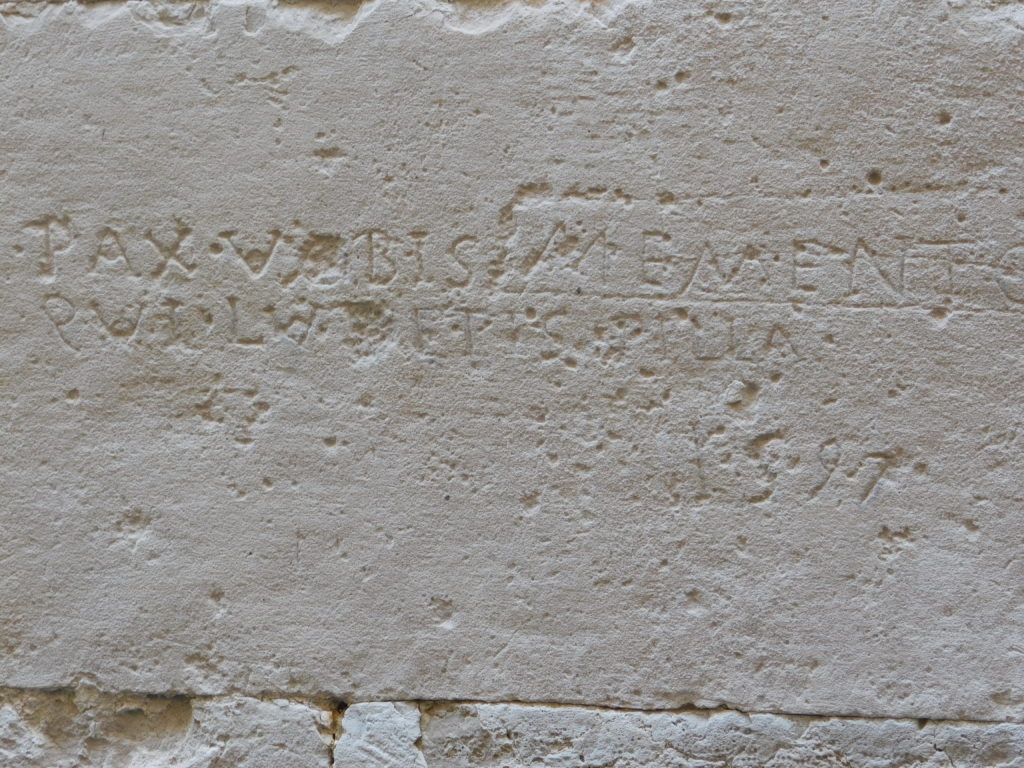

Finally, I’ll return to our morning walking tour. The photo is of what our guide called the oldest graffiti in Dubrovnik which, you will see, is carved into a wall. The story is that a priest lived in the house and children playing ball outside continually disturbed his afternoon siestas. (Note that the date is 1597 so per our guide, it’s also among the oldest mentions of children playing ball in Croatia.)

The priest is reputed to have warned the children repeatedly not to disturb his sleep but, children being children, they of course ignored him. Eventually, he carved this on his wall:.

The reference to playing ball is above the scratches visible in the photo. I don’t recall all of the Latin but the first line reads “Pax vobis memento” and the full translation including what is visible and not visible is: “You who are playing ball, Peace be with you, Remember you will die.” So, yes, even in 1597, cranky old men were essentially yelling, “Hey you kids! Get off my lawn!”