This chapter will reveal why I include a geological supplement for each stop on this Olympic host cities tour. It’s not that I have a consuming interest in tectonics but I do have a compulsion for puns and now, as I prepare to write about the geology of Beijing, I get to write about

The Plates of China.

While I could limit our look to the very big picture, and claim that China lies atop the Eurasian Plate that lies beneath most of Europe, Russia and China, I’m going to keep a more narrow focus. Most geological analyses describe seven major tectonic plates – the Pacific, North American, Eurasian, African, Antarctic, Indo-Australian, and South American. You can think of these as the dinner plates in the set and any other that I write or have written about as either salad plates or dessert plates. Or, if you’d rather, you can think of China as lying atop an actual plate that’s been dropped and broken with Mother Earth trying to reassemble it using magma as glue.

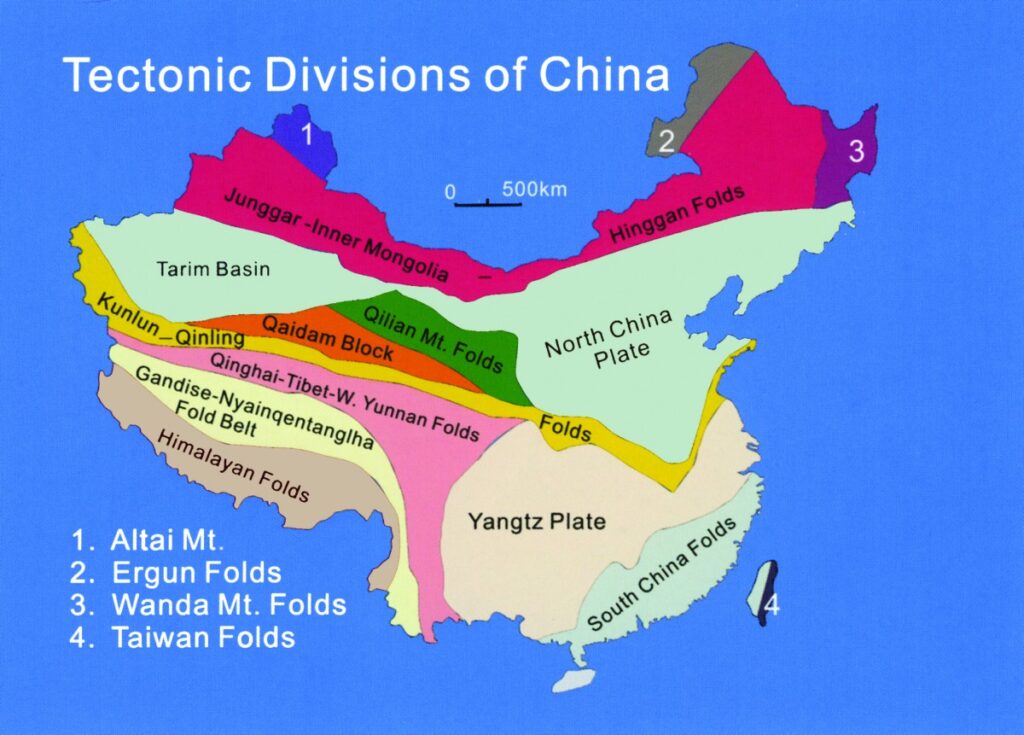

In the case of China, we can see some of these smaller plates or pieces of the big plate on the map below.

[Map from irocks.]

Let me proceed with some words of caution. As I write these summaries, I put substantial effort into reconciling different interpretations of the data and I try to present either my understanding of the most reasonable explanation or, if I can, by determining what I believe presents the consensus view. You should keep in mind that either my understanding or the consensus itself (assuming I’ve accurately identified that!) could be wrong.

As I wrote in the post about Japan’s geology, in the case of the eastern parts of Eurasia, the difficulty in finding this happy place is compounded because studies in this part of the world are more limited than say, the American west and because as one source put it, “Dating back the geologic history of Eurasia isnŌĆÖt straightforward.” So as you read on, a pillar rather than a grain of salt, might be the most appropriate amount of skepticism.

Yangtze go home.

Beijing sits atop the Yangtze Plate so that will be the area of emphasis in this section. (You didn’t really think I was going to pass up the pun in the header, did you?) A good general way to picture Eurasia is to see it as a mosaic of cratons. (As a reminder, a craton is a large, coherent section of Earth’s continental crust that has maintained long-term stability.) In the case of Eurasia these cratons formed and collided at very different times. The Yangtze Plate formed in the neoproterozoic (750 M Y A) when it separated from our old friend the supercontinent Rodinia, whereas the Indian Plate, whose northern edge underlies parts of southern China is a relative baby at a mere 150 million years old. (I mention this for two main reasons. First, I want to give you some idea of the challenge of reconciling these geological forces and second because the collision of these two plates provided the energy for the Longmenshan orogeny.)

Although it’s surrounded by mountains – the Yan Mountains to the northeast (which will host the skiing events of the 2022 Olympics) and the Jundu Mountains to the west – Beijing itself is not at all mountainous. The city lies in the North China Plain (Huabei Pingyuan) and is generally between 30 and 40 meters (100-130 feet) above sea level.

The tectonic framework of continental China has been fundamentally in place for about 250 million years (early Mesozoic). This allowed the formation of the North China Plain – a half-graben large-scale down-faulted rift basin. (Although it sounds like it could be a trick in gymnastics – “For her dismount, she’ll be doing a double Salto forward tuck with double twist and a half-graben.” – it isn’t. A half-graben is simply a geological structure with a fault along one of its boundaries. A full graben has faults on both boundaries.)

After the early Cretaceous, the Pacific plate subducted under the Asian continent creating lithospheric thinning and strong intracontinental rifting. This process is important since a rift is created in a region that extends as two parts of the Earth’s lithosphere (upper crust) pull apart. The crust thins and sinks, forming a rift basin.

[Map from charismaticplanet.]

The crustal thinning and sinking allowed space and time for the creation of an alluvial plain that, in this instance, was largely built by sedimentary deposits from the Yellow Sea, the Huang He River (Yellow River), and the Yongding River. Beijing itself is located about 150 kilometers (90 miles) from the Bohai Sea – an inlet of the Yellow Sea – that narrows into Bohai Bay.

The deposit of sediment in the North China Plain by the two rivers and the Yellow Sea is a relatively recent development occurring mainly throughout the Paleogene and Neogene periods. Thus, we can conclude that the North China Plain is relatively young as the sediment comprising it has accumulated over only the last 66 million years.

The location of the Chinese capital city has so many advantages that a subspecies of homo erectus, Homo erectus pekinensis (commonly called Peking Man) occupied the area at least 250,000 and perhaps as long as 780,000 years ago and can be seen in the Zhoukoudian Caves and Museum some 60 kilometers (37 miles) southwest of Tiananmen Square. Further, there’s some evidence that Beijing has been inhabited by modern humans for about 27,000 years.┬Ā And that, will be the subject of the next chapter.