Bing Banff Boom

A Brief Forward.

People can benefit from travel in many ways but adaptability might be among the more unexpected. Sometimes, no matter how carefully planned a trip might be, circumstances arise that necessitate change. When they do, I’ve found the best course for me is to adapt and find an alternative.

My experience at the auto rental counter in Calgary which, at times, felt tangentially related to a Seinfeld episode presented the opportunity for me to display some equanimity but also, as I see in retrospect, proved portentous regarding the next few weeks. It began with an unduly cumbersome process to simply pick up the car.

I waited in line to reach the desk where I confirmed my reservation. After providing reams more information, enduring the pitches to purchase this, that, or some other type of additional insurance I learned that the company imposed a $10 per day surcharge for taking the car out of the province of Alberta. There was the usual attempt to upsell me to a larger car. I declined, telling the agent I’d reserved and wanted the smallest car available.

I then had to take a seat across the lobby and wait for my name to be called at which time they’d provide the keys, have me sign additional paperwork, and direct me to the car’s location. This required nearly 20 minutes. When the agent called my name, she told me they had upgraded me to a full-sized car but would do so at no additional charge. She was not only shocked when I insisted that I wanted the compact car I’d reserved but told me that she didn’t know if they had a compact car available.

I told the agent that I’d find a sub-compact more acceptable than a larger car.

Another 20 minutes passed before they managed to scrounge up a Honda Civic – one I assumed had been very recently returned because it hadn’t been vacuumed or washed. The agent then waived all but two days of the out of province surcharge. By this time, I was hungry and had spent more than an hour and a half longer in the airport than I’d anticipated so I made no attempt to negotiate the waiver of the final two days. However, the delay meant bypassing some of the places I’d wanted to visit between the airport and the park.

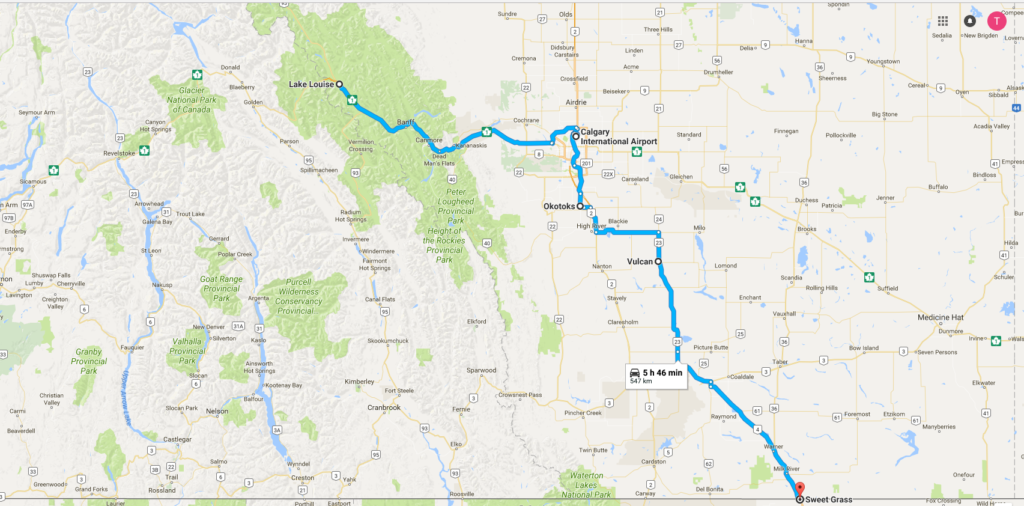

Although the primary focus on this trip will be the time I spend in Wyoming and Montana, I started in Canada’s Banff National Park nestled in the Canadian Rocky Mountains which have their northern terminus at the Laird River in the northeastern corner of the Yukon Territory and end at the U S border in the south. As for my route in Canada, it looked generally like this (though I’d use AB2 on my return to Calgary):

If you enlarge the map, you can complete my Alberta circle. Look directly west from Sweet Grass and find Carway. Follow AB2 north toward Calgary. This is my route north from Glacier National Park.

The American Rockies span parts of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and even dip into northern New Mexico. So, while none of the mountains I visited in my recent trip to Arizona and Utah are part of the Rocky Mountains, all the mountains on this trip will be. Since it’s a two-and-a-half-hour drive to reach Moraine Lake Lodge where I’m staying in Banff, we have lots of time to study the Rockies.

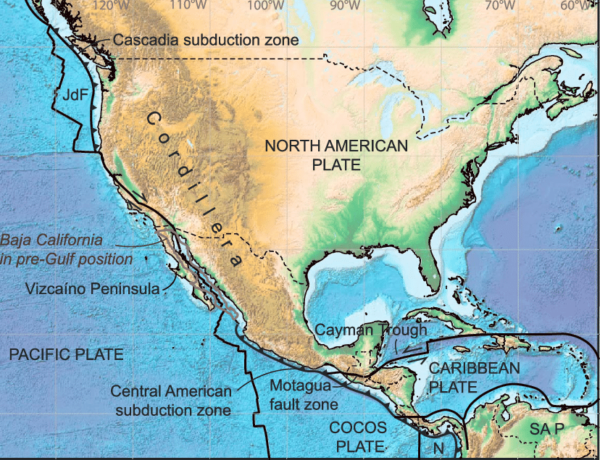

The full expanse of the range includes many subranges and the Rockies themselves are part of the North American Cordillera.

[Map from Research Gate.]

(A cordillera is a chain of geologically related mountain ranges.) The North American Cordillera stretches from the Southern Alaska Range which includes Denali, the highest peak on the continent, to the three Sierra Madre ranges in Mexico. Along the way, we’ll see that these mountain ranges have complex structures because they combine mountain building through folding and faulting processes with some volcanic activity.

ROCKY MOUNTAINS.

How did the Rockies earn their name?

For those of you who have been to the Rockies or seen photos the answer to this question might seem self-evident but objectively, it’s difficult to discern any observable difference between the mountains of this range from many other mountain ranges in the American west. In fact, an article in the Denver Post notes that 18th century Spanish explorers and soldiers coming from the south referred to sections of the Rockies as La Sierra de la Grulla (Mountains of the Crane) and La Sierra del Amagre (Mountains of Red Earth).

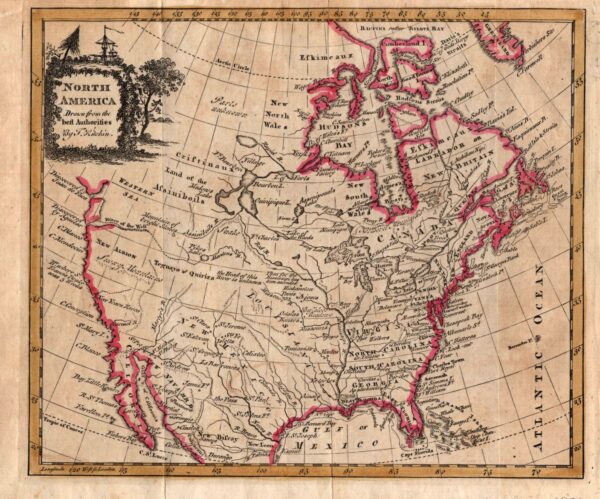

Coming from the east, as evidenced by a 1730 map, the earliest French explorers called them les Montaignes de Pierres Brilliantes or Mountains of Bright Stones often translated to English as Shining Mountains.

[Map from Museum of the Big Bend].

However, according to Robert Hixson Julyan’s book Mountain Names, French trappers and traders, accustomed to “rounded, forest-clad mountains” in the East translated the Cree phrase as-sin-wati meaning “when seen from across the prairies, they looked like a rocky mass” into les Montaignes Rocheuse. This then translates into English as Rocky or Stony Mountains and, while Thomas Jefferson used the latter term, other European-Americans coming from the east generally used the former. Now you know the full story.

So, you want to make a mountain.

In reporting my wanderings through Arizona and Utah several weeks ago, I focused much of my geological discussion on the process of uplift because it was so important to the formation of so many of the canyons I visited. Uplift, or more specifically isostatic uplift, is one of the tectonic forces that create mountains. The tectonic partners of isostatic uplift are intrusion of igneous matter and compressional forces. In its own way, each of these processes, known collectively as orogeny, force surface rock upward creating a landform significantly higher than the surrounding features. We call that landform a mountain and there are three main types – block (sometimes called fault-block), volcanic, and fold.

Block mountains.

Because it passes through or near some of the country’s most densely populated areas, most Americans likely have at least a nominal familiarity with California’s San Andreas Fault. The San Andreas Fault is the boundary between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates. (A tectonic plate is a sub-layer of the earth’s crust – also called the lithosphere – that moves, floats, and sometimes fractures.) When tectonic plates interact, the result contributes to any or all the following: continental drift, earthquakes, volcanoes, mountains, or oceanic trenches.

When faults move against one another, the rocks on one side of a fault rise relative to rocks on the other in the process known as uplift or rifting. The uplifted blocks become block mountains (also known as horsts) while the intervening dropped blocks are known as graben (i.e. depressed regions). These block mountains break up into chunks and move up or down. Fault-block mountains usually have a steep front side and then a sloping back side. It’s just this sort of interaction that gave rise to California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains or that we see at Mount Rundle

looming over the town of Banff.

Fold Mountains.

When two plates rub against one another at a fault line they create block mountains. When they meet in a head on collision, they create fold mountains. As they collide, the edges of each tectonic plate crumple and buckle forcing the less dense crust to float on top of the denser mantle rocks. The material being forced upward forms hills, plateaus and, over time, mountains. This is the most common mountain building process on earth and is the process that built not only the Rocky Mountains but the Appalachians, Himalayas, Alps, Andes, and others. (There are some problematic issues concerning the Rockies – especially in the U S but that’s for a later discussion.)

Volcanic mountains.

Everybody and everything likes being cool. When people get hot, they sweat to release heat and get cool. When dogs get hot, they pant (and slobber a bit). To cool itself, the Earth pushes its hot magma toward its surface. As it rises, gas in the magma forms bubbles that create intense pressure forcing the surface rock upward. If the source remains in place, eventually something’s got to give and the magma erupts as lava, ash, rock, and volcanic gases. When this material builds up around the volcanic vent, it creates a volcanic mountain. Japan’s Mount Fuji and Mauna Kea in Hawai’i are among our planet’s iconic volcanic mountains.

Another type of volcanic mountain is a dome mountain. Sometimes, magma pushes toward the earth’s surface but before it finding an outlet and erupting, the source of the magma disappears allowing the molten rock to cool and harden into a dome-like shape. Mount Saint Helens in Washington is a dome mountain.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

2 responses to “Bing Banff Boom”

So hard to read this on a cell phone after you’ve been traveling all day, then had a three-course meal + included alcoholic beverage.

PS if your Spanish students are into geology, you are golden.

But did you start your day with the breakfast of champions?