Preface.

I’ve reached the point in my Olympic host cities tour where I’ll be revisiting cities that I have written about elsewhere in this blog. Many – such as Beijing which is the leadoff city for this segment – I’ve covered in great detail whereas I’ve treated a few, like Lillehammer, more sketchily. It’s unlikely that I’ll be bringing much new to these initial posts of my experiences in each of these cities but I plan to follow the established pattern of recounting my experience in the place, some Olympic Games highlights, a little geology, and a little history and archaeology.

On this particular trip which took place in June 2013, I landed in two host cities. The first is Beijing and it was literally the first stop on the trip and the second is Moscow which was the trip’s penultimate stop. If you want to experience the entirety of the Trans-Mongolian Express, you can do so here.

And now, on to Beijing.

The initial stop for our group’s first full day in Beijing was Tiananmen Square and we not only had to pass through a security checkpoint to enter the Square we’d had to do the same to get on the Metro. The Chinese take security very seriously.

At 44 hectares (about 109 acres) Tiananmen is among the largest city squares in the world and can accommodate over 1,000,000 people. It was designed and built in the middle of the 17th century and is four times larger today than its original configuration. This picture is merely the south section of the square looking from west to east and the haze is the smog that hovered over the city for most of our visit.

The gate tower on the right of the picture was the southern entrance to the Imperial City which housed granaries, temples, and high officials of the empire. The Forbidden City – which we would soon visit – housed the Emperor, his concubines, and immediate family only.

We passed through the square from south to north toward the Tiananmen Gate also known as the Gate of Heavenly Peace. It serves as the south entrance to another section of the Imperial City and is closer to the Forbidden City.

Lest you think that the Forbidden City (more photos here) is small because it housed only the royal family, let me disabuse you of that notion. Some emperors had as many as 3,000 concubines each with her own bedroom.

Next, the Summer Palace.

The Summer Palace occupies grounds about forty minutes by Metro from central Beijing. Our Tiananmen guide led two fellow travelers and me to a bus which we rode to its last stop and exited into one of the old traditional neighborhoods that once comprised most of Beijing.

Along the main street we spotted a moderately busy restaurant and stepped in for lunch. Though there were no English translations the menu was, as many in Asia are, pictorial. There was still some guesswork involved and we ended up with breaded fried fish pieces (bone in) in a brown ginger garlic sauce, rice with vegetables, shrimp, and pork that had a soupy consistency, and something green that none of us could identify but that seemed reminiscent of a Korean dish I’ve had. I tried to order a Tsing-Tao and the young waitress seemed confused because they served a different brand of beer. Since we’d been advised to drink only bottled water, I accepted the “house” brand.

After lunch we took a cab to the Summer Palace. The fare was 44 yuan – about half what we’d been told to expect. The Imperial City is large but the Summer Palace at 290 hectares (716 acres) is three times the size of the former. It feels vast beyond words. It’s largely a monument to the ego and excess of the Dowager Empress Cixi who effectively ruled China for nearly half a century beginning in about 1860.

[From Wikipedia – Painting of Cixi by Hubert Vos – Public Domain.]

We walked through the grounds in the peak heat of a hot day stopping at places such as the Garden of Virtue and Harmony which proved not to be a garden at all but a theater where Cixi would watch performances of Chinese Opera. We were fortunate enough to reach there in time to see a short performance.

The combination of the heat and trudging up and down uneven steps and hills took a toll so we stopped for ice cream on the way to the Tower of the Fragrance of the Buddha. The tower is a three story octagon and is about thirty six and a half meters tall. It’s something of the centerpiece of the Summer Palace landscape. Inside the tower is a bronze cast statue of the thousand-handed Guanshiyin Buddha.

Had it not been for the smog, some of the views of Beijing to the east and the mountains to the west as we climbed Longevity Hill (the highest point in the city with an elevation of 109 meters or 358 feet) to the Tower and then higher would have been spectacular but alas were more than a bit enshrouded. Honestly, I shudder to think of the particulate matter I was inhaling. It was tangible enough to dispel any concerns about second hand cigarette smoke.

Our final stop was Suzhou Street. It’s a quaint supposed reproduction of a street that would have served the Palace workers but wouldn’t have been a part of it. Really, it’s a place to induce tourists to spend money. I can’t fault the effort. Here’s a link to additional photos of the Summer Palace.

THE GREAT WALL.

Technically, the Great Wall isn’t in Beijing but I’d be remiss to exclude it in any recounting of a trip to China. The ride to the wall took about two hours and we arrived in a steady rain. The street leading up to the entrance is lined with shops of various sorts and I was able to negotiate the purchase of a lovely lavender poncho for one U S dollar. The Wall was accessible on foot if one was willing to make a 30 minute climb up a steep hill but our group had only two and a half hours allotted to spend on the Wall so I opted to ride up on an open cable car chair lift. When I stepped onto the Great Wall, this was my view (and here are some others):.

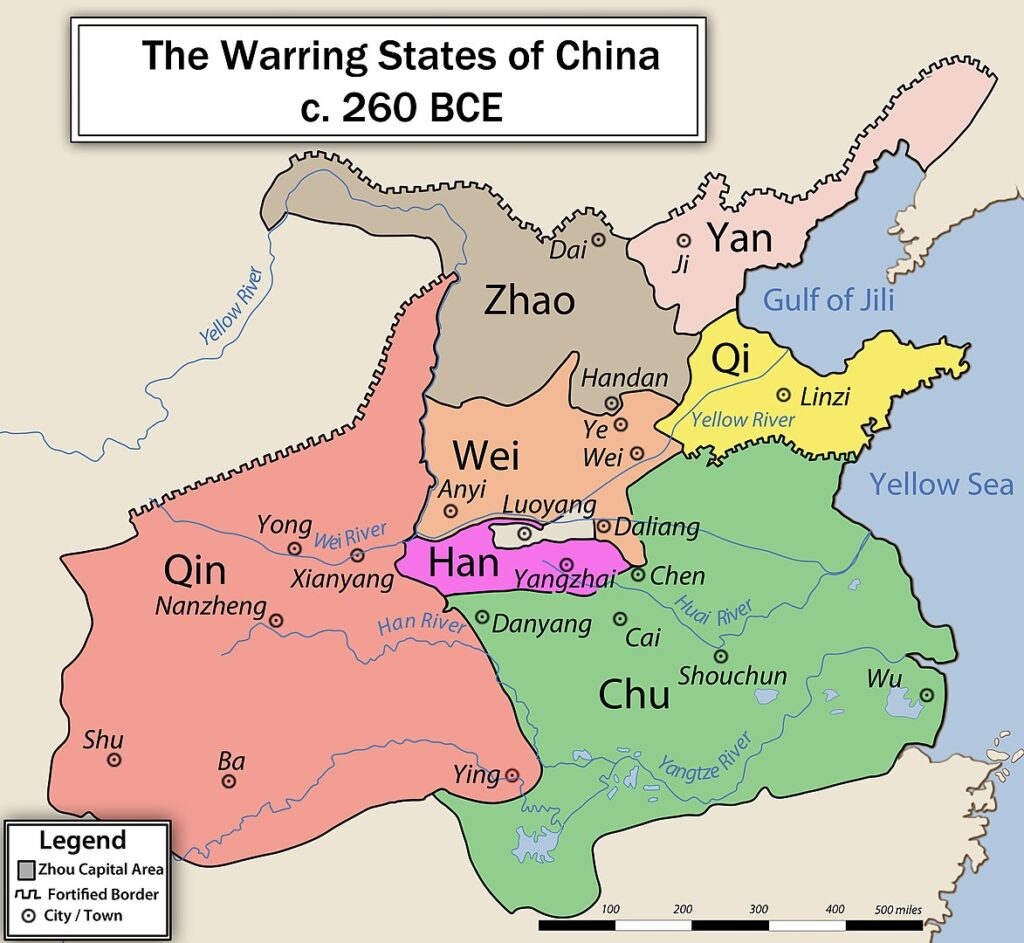

You should know that the Wall was not originally conceived as a single construction. Many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years before the Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who was the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that these earlier fortifications be joined into a single system that would extend for about 5,300 kilometers (3,300 miles). The ostensible purpose was to protect China from northern invaders but the 250 years before the Qin Dynasty came to power in 221 BCE was known as the Warring States Period.

[Map from Wikipedia BY Philg88 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.]

Thus, Qin may have had a dual purpose in mind. Remember that a wall built to keep one group out can also be used to keep another in.

Over the centuries the Wall was neglected. It fell into disrepair and was rebuilt several times. The Wall as we know it today took its greatest shape from the middle of the 14th century to the middle of the 17th century during the Ming Dynasty. The real burst of construction began in the last quarter of the 16th century as the Ming rulers sought a largely defensive position from a possible invasion from Manchuria. In 1644 the Manchus from central and southern Manchuria broke through the wall and established China’s last dynasty – the Qing – that ruled until 1912. They established their capital in the former Mongol city of Dadu established by Chinggis Khan as a series of connected hutongs and renamed it Beiping which became present day Beijing. (Hutongs are alleys formed by joining lines of traditional courtyard residences which become a neighborhood and then a community.)

If you’re interested in reading more, use the link at the end of the preface. In the next chapter, we’ll look at some noteworthy facts from the 2008 Olympic Games.