Before the Inka’s Machu Picchu there was Tiwanaku

And concurrent with Tiwanaku there was Moche, Huari, and Nazca. Before all of them there was Chavín. And before Chavín was the Caral-Supe. And this is an abbreviated list as these are just a few of the cultures that populated pre-Columbian South America.

The more I travel, the more I learn. The more I learn, the more I recognize the many gaps in my knowledge. Some of you might have shared a similar experience to mine. At some point in the course of my education, some unremembered history teacher touched upon two of the great Mesoamerican civilizations – the Aztec and the Maya. That same teacher was probably the one who also gave some passing recognition to the Inkas. I think from a largely Eurocentric point of view these three – Inkas, Aztecs, and Mayans – were worth mentioning because theirs were the empires conquered by the Spanish in the first half of the 16th century. But among the truths about the Inka Empire are that it lasted barely a century and was the last in a line of rather remarkable civilizations and cultures that had had a presence along the west coast and in the high Andes for millennia.

(In a previous post I mentioned the archaeological controversy surrounding the dating of recent discoveries at Huanca Prieta that some believe indicate a human presence as much as 17,000 years ago. There is firm evidence in the stone quarry at Chivateros near the mouth of the Chillón River in western Peru of a neolithic culture dating to 9,500 BCE.)

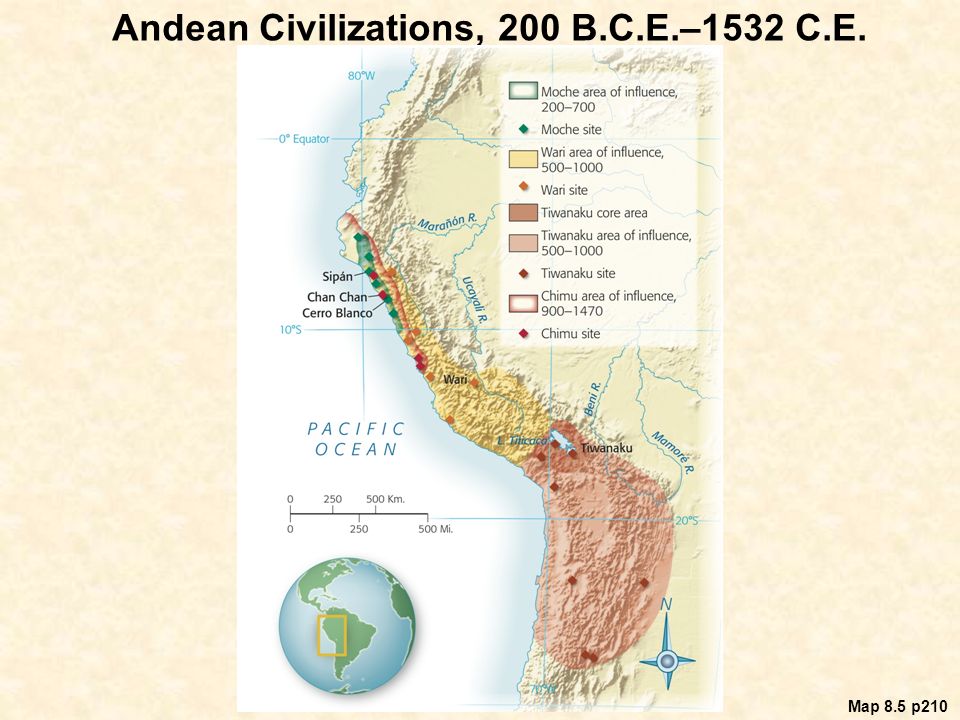

Naturally, the further back in time we try to reach the sparser our information becomes and any conclusions we attempt to reach become more speculative. But the slide below provides some idea of some of the range of just a few pre-Inkan cultures and describes some of their resourcefulness in adapting to the challenges of living in the high Andes.

In the Andes, relics from the Chavín culture are often marked by that group’s distinctive art styles and, while not shown on this image, the Caral-Supe or Norte Chico was a coastal society dating to at least 3,500 BCE – in other words, about the same time the Egyptians were building the pyramids. (The discovery about a decade ago of a circular plaza made of rock and adobe at Sechin Bajo, located about 330 kilometers north of Lima, predates the Great Pyramid at Giza and, at an estimated age of 5,500 years, is currently considered to be the oldest known human construction in the Americas.)

If you look at the map above, close to Lake Titikaka you will find Tiwanaku. Located about 75 kilometers west of La Paz and accessible in a tour bus after a ride of one and a half to two hours, this is the site our merry group visited and where I invite you to join us.

Tiwanaku or not Tiwanaku, that is a question.

Unlike the famous contemplative existential question to which this section header alludes, this question is neither existential nor unanswerable. The existential aspect is imaginary and the answer is no. We do not know the actual name of the city though there is some speculation it was called Taypikala or “Central Stone”. Nor do we know if its residents had self-referential familial, clan, or tribal names. (Similar gaps will reappear throughout this journey.)

What we know is that Tiwanaku (sometimes rendered as Tiahuanaco) is a Quechua word. Quechua is the language spoken by the Inkas and it is they, (it was possibly the ninth Emperor – Pachakutiq) who applied the designation sometime in the 15th century. Tiwanaku culture arose in the first or second century CE, reached its peak in the sixth century, and all but vanished at the beginning of the eleventh. While I can’t tell you the degree of similarity between the archaeological remains we see in the city today and the city as Pachakutiq found it, the site had likely been abandoned for hundreds of years before the Inkas reached it.

The photo above is the seven-tiered pyramid called Akapana and I’ll provide a more in depth look at it shortly. But first, let’s start our visit at the Archaeological Museum on the site. Because of the fragility of the contents, our guide asked us not to take photos inside the museum. It was here, however, where we had our initial exposure to the intriguing possibility that the natives of Tiwanaku either visited other cultures around the world or received such visitors themselves.

In another demonstration of the importance of art in human culture, it’s the art of their sculptures and on their pottery that makes this speculation plausible. This art clearly depicts people with African, Asian and even Caucasian features. It also includes one of a bearded man in an area where facial hair is uncommon and, while it’s certainly possible that these are manifestations of the artist’s creative imaginings, given that ancient artists almost always limited their depictions to what was locally familiar, one has to wonder how these relatively alien images came to be in this place.

The museum’s unquestioned star is Bennett. Although Bennett, named for the American archaeologist Wendell Bennett who unearthed it in 1932, is the site’s star, we know little else about him. Soon after its discovery it was moved to an open-air temple outside the national stadium in La Paz where it suffered decades of degradation from weather and pollution and also the indignities of rifle assaults during various Bolivian uprisings. Bennett was returned to Tiwanaku in 2002 and the museum, in the Bolivian way, is still being constructed around him.

[Photo of Antonio Portugal from Wikimedia Commons BY Ajdavalos, CC BY-SA 4.0.]

In the next post, we’ll look at some of the practices of the Tiwanaku civilization.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

2 responses to “Before the Inka’s Machu Picchu there was Tiwanaku”

Hello Todd. I have been looking through the internet in search of clues regarding the meaning of the name Tiwanaku. According to you it means ‘ central stone’ and according to another website it means:

“it is a word that comes from two aymara words: “taypi”, ‘center’, ‘middle’, ‘hub’ and “kala”, ‘stone’, ‘rock’; so the meaning is: foundation stone of between.”

I was interested in finding multiple sources on this topic but the wikipedia page which says the same thing only comes up with one obscure book. Do you know of any scholarly/academic sources (in any language) that I can look up regarding this? Thank you.

Andy

I made this trip nearly five years ago and don’t recall the sources I used. I have checked my few remaining notes and don’t have any citations I can provide. However, I think the differences between your sources and my definition is simply a matter of interpretation since both refer to center (or central) and stone. I’m sorry I can’t be of any further assistance.