Repentant or depressed.

Severely chastened by his recent experience in Washington, by the time he reached Minnesota after his arrest in Chicago, George Armstrong Custer gave every indication that he was a changed man when he reported to General Alfred H Terry.

Although Terry was of a very different temperament than Custer, he held the Lieutenant Colonel’s military acumen in great esteem and truly believed he needed Custer to take part in the campaign against the Sioux. Facing an uncharacteristically repentant and desperate Custer, Terry urged Grant to reinstate his command of the 7th Cavalry. Sheridan and Sherman both supported this action and Grant, who had seen both some of his own public standing erode and a groundswell of support growing in favor of Custer, concluded that he needed a decisive victory over the Indians, acceded to the requests of his generals.

(The Republicans failed to nominate Grant to run for a third term choosing Ohio governor Rutherford B Hayes to run against the Democratic Party’s nominee, Samuel J Tilden. Tilden won the popular vote in what remains the highest {by percentage at 81.8} voter turnout of any U S presidential election but failed to secure a majority in the electoral college. {When considering voter turnout, keep in mind that while African-American men could ostensibly vote in this election under the rights granted by the 15th amendment to the Constitution, the 19th amendment granting women the right to vote was still 44 years in the offing.}

Tilden claimed 184 electoral votes – one shy of the 185 needed to win – while Hayes had clear claim on 166 with 19 in dispute because the Democrats claimed that corrupt, Republican controlled election boards in the southern states of Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina had overturned Democratic popular vote majorities and awarded their votes to the Republican.

Democrats controlled the House of Representatives and Republicans controlled the Senate and the two houses were unable to decide who should count the votes. For the only time in American History, Congress named an Electoral Commission comprised of five justices from the Supreme Court and 10 members of Congress. The 15-man commission voted 8-7 along party lines to give all 19 disputed votes to Hayes who then became the 19th President of the United States.)

One unintended consequence of this delay was that it provided time for Crazy Horse

[Photo of Crazy Horse from Indians.org.]

and other leaders to rally even more men to their cause. Perhaps of greater importance, it also allowed some sutlers to continue selling arms to the Native Americans and it’s been theorized that those First Peoples went into that battle better armed than the troops they faced.

Setting out on the campaign.

Despite this almost miraculous reprieve prompted by General Terry’s confidence in him, the Custer who returned to Fort Lincoln and prepared to lead his troops into battle did not appear to be the same brash man that many knew. Many of the enlisted men and some of the officers noticed that Custer often seemed preoccupied during the march from Fort Lincoln across North Dakota toward Montana. Some described him as reticent and not the talkative commander to whom they were accustomed. Certainly, Custer would have been focused on the usual military issues regarding transporting and protecting his supplies or disagreements over battle plans but it also raises the question of whether Custer might have been suffering from depression and, if so, whether that would ultimately affect his decisions at Greasy Grass.

One of the officers who challenged Custer’s plans was Captain Benteen. The friction between the two dated back at least as far as the incident at Washita which Benteen thought was unduly rash because Custer had failed to properly scout the Cheyenne village and which had, in fact, nearly resulted in disaster for the 7th Cavalry. Also, in his report to General Sheridan about the battle, Custer omitted commendations for anyone under his command – a practice that was the norm at the time. Given his claim of the scope of the victory, this omission was particularly glaring.

Further raising Benteen’s ire, Custer’s report to Sheridan made little reference to casualties. He failed to note that he had abandoned Major Joel Elliot and 16 others on the battlefield. According to Benteen, Custer had made no attempt to locate the bodies which were found together in a tight circle when the regiment returned to the battlefield on 11 December.

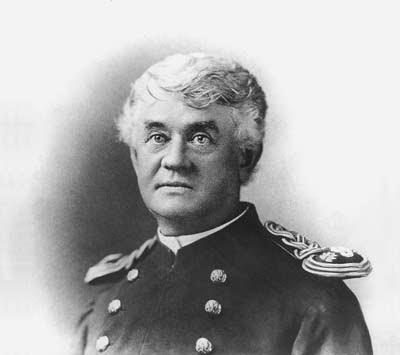

[Photo of Frederick Benteen from The LIttle Bighorn Associates.]

It’s likely, however, that the greatest source of animosity between the two came about in 1873 when Benteen and his family reported to Fort Rice in the Dakota Territory. In June of that year, the 7th Cavalry led the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 and on 31 July, Custer ordered Benteen to remain behind at what became known as Stanley’s Stockade, a supply point on the Yellowstone River.

As the fall turned to winter, Benteen received word that his daughter, Fannie, barely 18 months old had fallen very ill at Fort Rice. Custer, who had himself gone AWOL to visit his sick wife, denied Benteen’s request for leave to return to Fort Rice and before they could resolve the issue, Fan had died.

It’s unlikely that this disagreement with Benteen was much on Custer’s mind as he led his troops to Montana but it’s certainly possible that Custer felt some residual humiliation from having abased himself in front of General Terry in his pleading efforts to regain his command. Perhaps He was wondering whether some bold action that led to a great victory would restore his reputation in the eyes of President Grant.

After separating from General Terry at the confluence of Rosebud Creek and the Yellowstone River, Custer led his troops south along snow covered ridges to the reported Indian camp at Little Bighorn. What did Custer see when he looked at the village along the Bighorn River the day before the battle? Here’s one depiction of the battle from History.com.

Some historians have speculated that, for the first time in his career, Custer underestimated his enemy. Others think his earlier successes against superior forces both at Gettysburg and Washita might have left him overconfident. And, of course, there’s the question of the impact of the fallout from the Trading Post Scandal. As I noted at the outset, Custer was a complicated man and I hope you now see that many factors could have been in play in the lead-up to that fateful day.

Although Reno and Benteen and several hundred troops under their command would survive the battle, Custer would make a series of decisions that all but certainly sealed his fate and that of the men he led to Last Stand Hill.