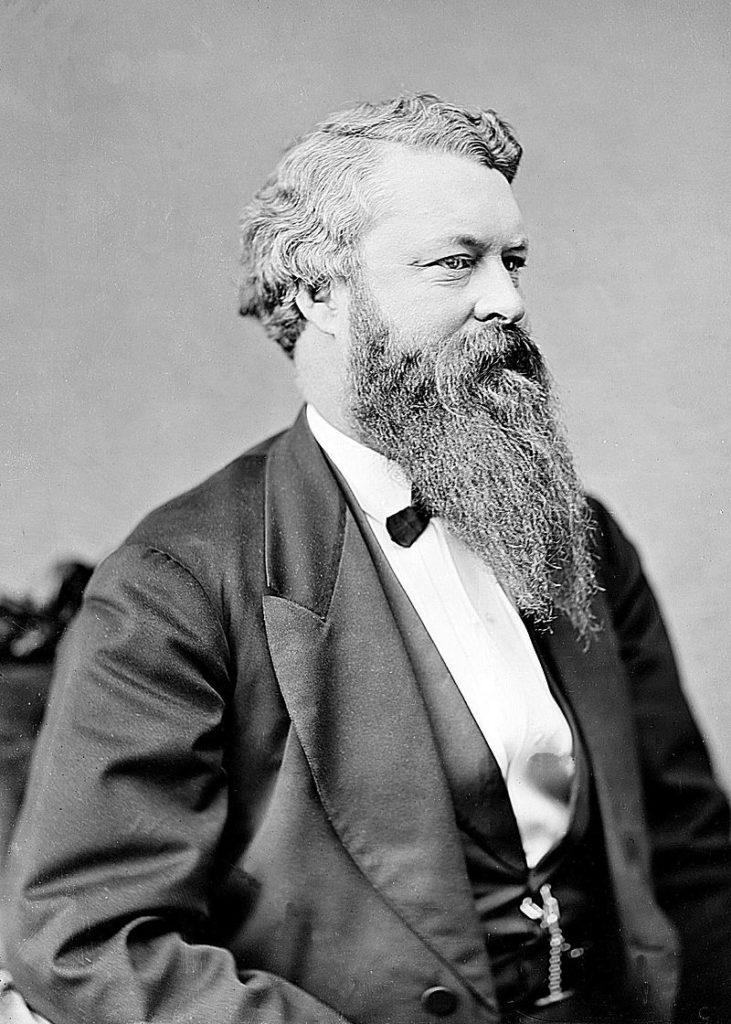

Some three years after his success at Gettysburg on 28 July 1866, Custer received his commission as lieutenant colonel of the newly created 7th Cavalry Regiment which was initially headquartered at Fort Riley, Kansas. While there, he took on several roles and, as was his wont, also got himself in a bit of hot water when he went AWOL to visit his wife. But Major General Philip Sheridan, who had become one of Custer’s great allies during the Civil War, arranged for his release from the prison at Fort Leavenworth.

[Photo of Philip Sheridan from American Battlefield Trust.]

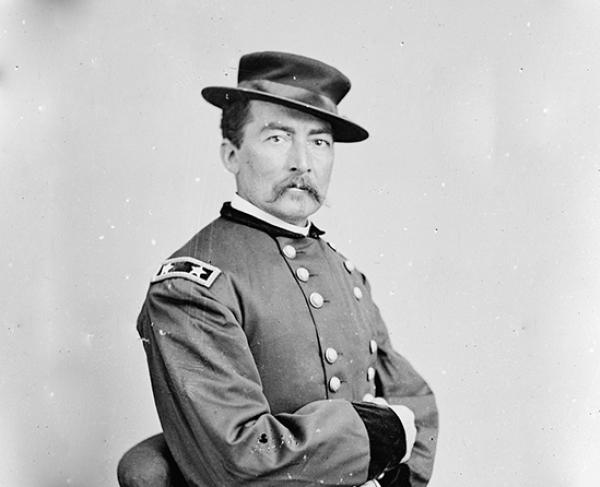

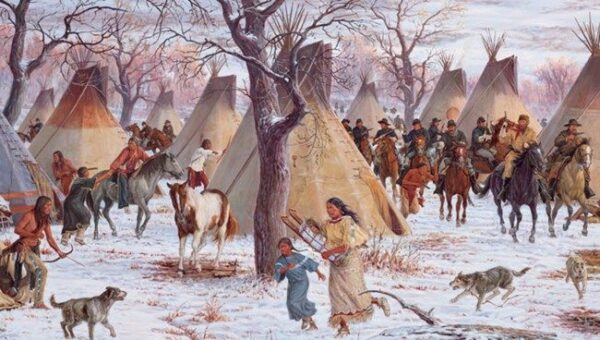

Sheridan was planning a winter campaign against the Cheyenne and wanted Custer to lead the 7th Cavalry in an attack on the camp of Chief Black Kettle. The raid occurred on 27 November 1868, and became known as the Battle of Washita River. Employing a tactic he would later incorporate into his battle plan at Greasy Grass and planning to attack at daybreak, Custer divided his force into four parts. This he did with the same rashness that had served him so well in the Civil War. Many of the officers serving with him felt this sort of attack had needlessly risked the lives of his men. One of the officers who held that view, Captain Frederick Benteen, would be in command of Company H on 25 June 1876 where he would make a decision that likely saved his life, the lives of his men, as well as those under the command of Major Marcus Reno but that also likely sealed the fate of Custer and the troops he led into that fight.

Another part of Custer’s strategy was targeting women, children, the elderly, or disabled for capture and later using them as human shields.

[Battle of Washita by Steven Lang from Legends of America.]

In his book My Life on the Plains, published in 1874, Custer justified this strategy, “Indians contemplating a battle, either offensive or defensive, are always anxious to have their women and children removed from all danger…” In his accounts of that battle, he likely overstated the number of Cheyenne warriors killed while understating both the number of his own troops and the number of Cheyenne women and children killed. Still, his victory at Washita River was considered the first major U S victory in the Southern Plains War and only enhanced his reputation.

Fate steps in and it’s a real scandal.

Recall that several years before the battle at Little Bighorn, Custer and the 7th Cavalry had transferred to Fort Lincoln in North Dakota. (It was from here that he led the 1874 Black Hills Expedition.) Also recall that General Alfred H Terry had developed the plans for an assault on the Sioux Cheyenne, and Arapaho in the unceded territory, all of whom President Grant had deemed “hostile” because of their refusal to be corralled on a reservation. Terry planned to set out sometime in the first week of April 1876. However, a Washington scandal that had been brewing in the background of the Plains Indian Wars for several years bubbled to the surface just as Custer prepared to march from Fort Lincoln. It was known as the Trading Post Scandal.

The U S military’s use of civilian contractors is not a recent development. In the 19th century, the Army contracted with what were known as sutlers – private contractors to run a base’s supply store. As has been the case with many military contractors throughout history, these men found ways to make their contracts remarkably lucrative. Soldiers had to purchase most of their own supplies and, facing no competition, the sutlers could sell their goods at higher than market prices. In the plains and the west, these traders also managed an extensive black market trade selling weapons and other goods to native tribes that were then often used against the very soldiers these traders were contracted to supply. In 1870 or so, Congress gave the Secretary of War (at that time William Belknap) the exclusive right to appoint post sutlers.

[Photo of William Belknap from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

In that year, the post at Fort Sill in Oklahoma had a sutler named John Evans but somehow Belknap’s wife, Carita, managed to persuade him to appoint a fellow named Caleb Marsh as sutler. Not eager to give up his tradership, Evans offered Marsh a deal. Evans would continue to trade but would share his profits in the form of quarterly payments of $3,000 to Marsh. Marsh, as it turned out, shared half his payments – the equivalent of approximately $60,000 per year in 2017 – with Carita Belknap.

Carita (Carrie) Belknap died some time in December 1870 shortly after giving birth. Belknap continued receiving the payments for the “care of their child.” Though the child died in 1871, Marsh’s payments continued to flow to Belknap and the payments continued even after he remarried in 1873.

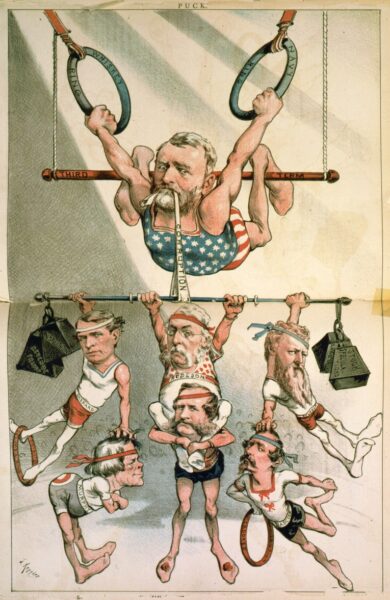

In late 1875 and early 1876, a series of articles citing what we would call today anonymous sources appeared in a New York newspaper prompting a Democratic controlled House of Representatives to begin an investigation. Hoping to avoid impeachment, Belknap resigned. Despite this, the House voted to impeach him and a Senate trial ensued in which a majority of senators voted for impeachment but which fell short of the requisite two-thirds needed to convict because some senators felt they couldn’t convict a resigned official.

You might wonder what all this has to do with Custer. Rumors began to circulate that Custer had not only been the source of those leaks but had helped to author at least one of the articles of impeachment. In March 1876, he was summoned to Washington to testify in Belknap’s trial which he did on two occasions – 29 March and 4 April.

It’s certainly plausible that Custer did leak at least some of the information that found its way to the New York papers. Sometime in 1875, while stationed at Fort Lincoln, Custer noticed that his men seemed to be paying unusually high prices for their goods and supplies. He investigated the matter personally and learned that the sutler was keeping only $2,000 for every $15,000 in profits he generated. In his testimony, he concluded that the remaining $13,000 had to be going to an illegal partnership or possibly to Secretary Belknap himself.

[Cartoon from British publication Punch of Belknap {far right} and other corrupt Grant officials – from Emerging Civil War.]

But then his testimony became even more inflammatory. He accused President Grant’s brother Orvil of taking part in the scheme. As he continued testifying, he leveled more and broader accusations raising the temperature of the controversy ever higher. Even with the distance of history, it’s difficult to know which of Custer’s charges were true and which were more a reflection of offenses to the notions of honor and chivalry that were so much an essential part of his person.

Whatever their basis, it’s safe to say that Custer’s testimony accusing the President’s brother infuriated Grant and the ensuing firestorm, in which the Republican press accused Custer of perjury while the Democratic press portrayed him as a virtuous officer, raised Grant’s ire even further. Grant then ordered General Terry to appoint a new officer to lead the 7th Cavalry. It appeared that Custer was not going depart Washington with his command intact.

Seeking some sort of redemption, Custer tried to arrange a meeting with the president but Grant refused. Not knowing what else to do, Custer headed west to return to Fort Lincoln. When his train reached Chicago, one of his closest allies, General Philip Sheridan, acting under orders from another of Custer’s supporters General William T Sherman, arrested him and sent him on to Fort Snelling in Minnesota where General Terry awaited.