I ended the previous post with some random facts about the Inkas – a culture we’ll get to know more about over the coming days. But for now, as our bus draws ever nearer to the center of the Inkan Empire, let’s return to a discussion about the city of Cusco and its pre-Columbian development.

So much more to say – Seeds of Empire.

We will never know if Manco Qhapaq had dreams of founding an empire when he ousted three tribes and settled his ayllu in this particular valley but it was certainly an advantageous place to inhabit. The basin in which Cusco sits lies on an ancient glacier lakebed surrounded by mountain peaks. The fertile soil of the valley had the potential to support diverse agriculture and the surrounding hills provided not only a natural defensive barrier but ample pastureland. The area had abundant water with the Huatanay River flowing just south of the early settlement and the Willkamayu River (more commonly called the Urubamba) flowing nearby through the area we tourists call the Sacred Valley.

[18th century painting of Manco Qhapaq from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

While there’s no timeline establishing the reign of Manco Qhapaq and his immediate successor, his son Sinchi Roq’a Inka, some sources indicate that it was under the latter’s rule that Cusco began to take shape as a legitimate capital since he’s the Inka believed to have built the first palace. Most indications are that the third ruler, Lluq’i Yupanki, came to rule in about 1260. He, too, built his own palace thus beginning a tradition that each ensuing Inka would follow. During the time of his son, Mayta Qhapaq, the fourth Inka, we begin to see evidence of the Kingdom of Cusco’s gradual expansion and the increasing importance of the growing city as its spiritual and administrative capital.

The seeds of empire were sown under the eighth ruler Wiraqucha (more commonly called Virococha). His reign began in the early 15th century and, according to the chronicle written by Miguel Cabello Balboa, he declared his intention to “conquer half the world.” He quickly embarked on his stated ambition. Under his leadership the budding empire saw major territorial expansion and, according to another writer Sarmiento de Gamboa, Wiraqucha was the first Inka to rule the territories he conquered. His reign lasted until a climactic battle between the Inkas and the Chankas an ethnic group occupying an area just to the west of the Cusco region.

(This photo is not that place. It’s just a look out our bus window.)

I feel the Earth move.

As the Inka culture was growing around Cusco, another group, the Chanka was flourishing just to its west. Because they typically settled in villages of about 100 people and were not as urbanized as the Inkas or their predecessors the Wari, the Chanka occupied a wide swath of territory. This drew them more and more frequently into conflict with the Inkas.

In 1438, (or at least some time between 1430 and 1440) the Chankas launched a major assault on Cusco. Wiraqucha fled the city taking two of his sons with him. A third son, Inka Yupanki was either left behind or refused to leave vowing to protect and defend the city. The climactic battle of the war is reported to have been the Battle of Yahuarpampa (translated as field of blood) or Saqsahuana.

According to an Inka legend, the outnumbered Inkas called upon their creator god Viracocha for aid. The god responded by turning rocks into stone soldiers.

[Image from Journey Machu Picchu.]

Aided by these Pururaucas, the Cusqueños, led by Yupanki, won the day. At least one report claims that 30,000 people – 8,000 Cusqueños and 22,000 Chankas – died on that field.

Until the time of the war with the Chankas, Wiraqucha had designated his son Inka Urko as his successor. However, it would be Inka Yupanki who would assume the throne. It’s not known whether this was the result of internal machinations by Yupanki or whether Wiraqucha had a change of heart as a result of Yupanki’s successful defense of Cusco. Regardless of the reason, Yupanki assumed the throne and it was he who would change the face of South America’s west coast.

After his ascension, Yupanki adopted the name of Pachakutiq which is commonly translated as Earth Shaker. (A 2006 BBC article states its meaning as “a change in the sun, a movement of the Earth which will bring a new era.”) Regardless of the translation, it was under Pachakutiq that the Kingdom of Cusco identifiably became the Tawantinsuyu and that the city of Cusco rose to even greater glory and importance.

The heart of the city moved to the north – a once swampy area that Pachakutiq had drained to make it habitable. The complex at Saqsayhuaman (which I’ll discuss in detail on our visit there tomorrow) was restored and expanded as was the sacred Qorikancha complex (which we will also visit).

There seems to be little question that the city was built and its expansion planned around four main roads that led to the four quarters of the growing empire. There is some question, however, regarding the claim that the city was laid out in the shape of a puma. This video provides the details. (If you don’t see the English translation, simply turn on the captions.)

(The Plaza de Hana Hawkaypata referenced in the video is called Plaza de Armas today.)

As the city developed in the 15th century, it was divided into two main sections. The northern hanan section sat at a higher elevation than its less prestigious lower counterpart – hurin. In addition to the plaza of Hana Hawkaypata, we find another nearby plaza called Kusipata where religious and state ceremonies were held with the Inka presiding. Residence in the city itself was generally limited to nobility, priests, and administrators. Farms and communities of artisans generally lived outside the city though it didn’t require extraordinary circumstances for artists and skilled crafts people to be forcibly relocated in the city and, of course, the city might have also housed some mitmaes.

In particular with the construction of the Qorikancha complex and its temple to the sun god Inti, Pachakutiq took deliberate steps to elevate the city of Cusco so its entirety would be seen as a sacred site. The Inka wanted the people of the Tawantinsuyu to think of Cusco as a venerable place.

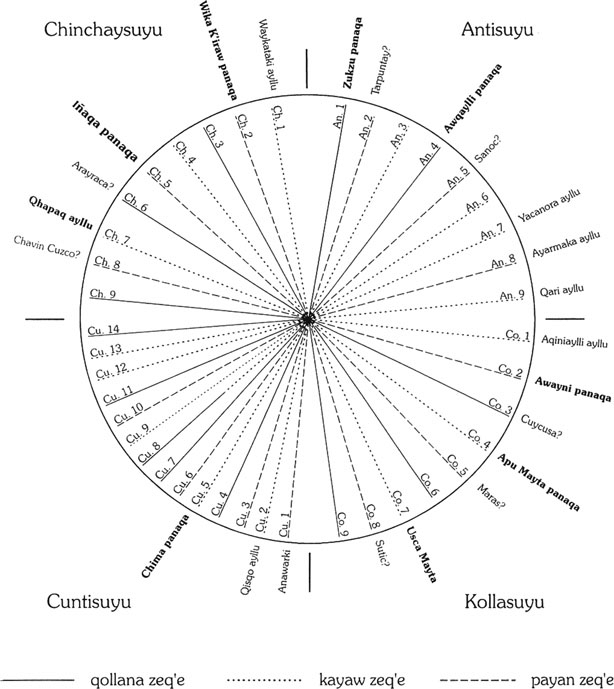

Thus, from Qorikancha, radiated the system of the zeq’e (ceque in Spanish).

[Image of the system of zeq’e from Researchgate.]

The zeq’e should be considered a part of the ritual landscape of the Inkas. The Inkas were deeply concerned with hierarchy, space (especially ritual space), and time. In addition to demarcating ritual space, the zeq’e were also an almanac and calendar.

The boundary lines of the four suyus radiated from Qorikancha. Forty-one (possibly 42) nearly straight pathways led outward from this spot in Cusco. The zeq’es were lined with 328 huakas – sacred places for the worship of gods, prayers, and sacrifices. Huaka can have several meanings in the religious practices of the Andean people. In this instance it refers to an energy force that inhabits, among other natural phenomena, waterfalls, rivers, mountain passes, and even the mountains themselves. Man made shrines might have been a simple pile of stones or highly complex stepped pyramids that rise throughout the Inka territory.

Qorikancha was the unifying force of the zeq’es. When subjects performed the proper rituals at a huaka, the zeq’e connected them to the spiritual center of the Empire. It was one way the Sapa Inka could unite his geographically dispersed subjects.

(The zeq’es were also divided along class lines. I’ll take a deeper look at them when I discuss the Inka road system in more detail. For now, keep in mind that their importance lies in their place of origin.)

Meanwhile, before I continue, here’s another peek out the bus window.