Technically it’s not a tapestry.

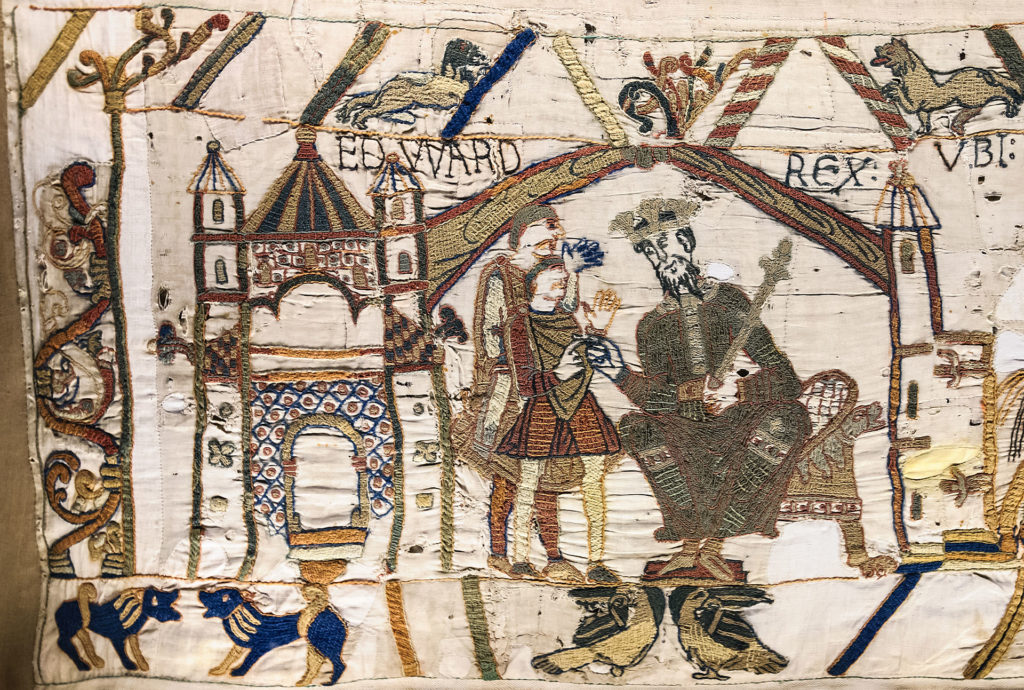

Taking a temporal leap of a mere 153 years, brings us to 1064 and to scene one

of the so-called Bayeux Tapestry depicting Edward the Confessor, then about 60 years old and without a direct male heir, sending Harold Godwinson to France. Harold’s charge (or so it is said) was to pledge his loyalty to William II (Duke of Normandy and a direct descendant of Rollo) because in 1052 Edward had promised William that it was he who would inherit the throne. We’ll return to the story shortly but first a few words about the work itself.

Asserting that something is true does not necessarily make the assertion true. Placing a label on an object does not necessarily make the label accurate. This is the case with the Bayeux Tapestry. Here’s a definition of a tapestry from our friends at Wikipedia,

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven on a vertical loom. Tapestry is weft-faced weaving, in which all the warp threads are hidden in the completed work, unlike cloth weaving where both the warp and the weft threads may be visible.

What we see in Bayeux is colored wool embroidered – not woven – onto the cloth. Thus, it would be properly called the Bayeux Embroidery not the Bayeux Tapestry. Now that you know the difference between tapestry and embroidery let’s put technicalities aside, and take a closer look at its creation and the story it tells or purports to tell.

As one might expect in trying to uncover the origins of a collaborative work of art that’s approaching 950 years of age, there are many unsolved mysteries. With no written record we can only speculate about such elements as who were the people who ordered it made, who were the people who actually made it, or the date of its first public appearance.

There’s some evidence that points to it having been commissioned by Odo – William’s half- brother and Bishop of Bayeux – and a work like this would have comported with both English and Norman tradition. For example, the 991 Battle of Maldon had been similarly depicted and presented to the Ely Cathedral. Buttressing this idea (but not with flying buttresses), the Bayeux Cathedral

was completed in 1077 and the 68.33 meters long embroidery fits almost perfectly around its nave. It’s conceivably a work that Odo might have commissioned to display at the Cathedral’s consecration and one that he could have thereafter displayed on each October 14 – the anniversary of the Battle of Hastings.

The earliest known written reference to the Embroidery (aka Tapestry) is in 1476 in an inventory of the cathedral’s property. Historians took renewed interest in it in 1729 when it was displayed in the Bayeux Cathedral. For those planning a visit, it’s expected that the Embroidery will, for the first time since its creation, leave France in 2022 to be displayed in the UK according to a statement issued by French President Emmanuel Macron in January 2018.

Here are some of the other interesting bits about the Embroidery:

It has 57 Latin inscriptions and depicts 49 trees, 41 ships, and 37 buildings among its inanimate objects. There are 202 horses, 55 dogs, and, 506 other animals – including those that are mythical. Of the 623 people appearing on the scroll only three are clearly identifiable as women in the main narrative.

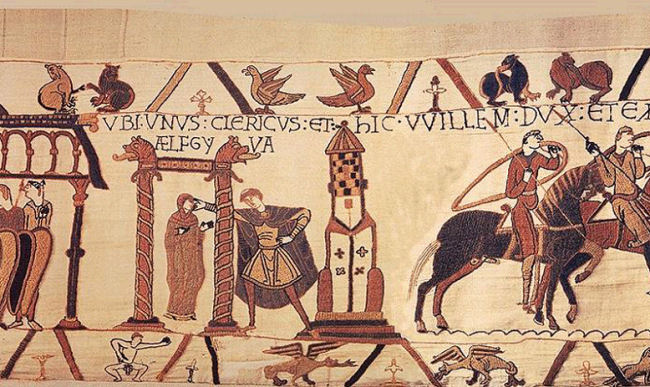

One is believed to be Edith who was Harold’s sister and Edward’s wife. The others are the “Fleeing Woman” seen in a building at the Battle of Hastings and my personal favorite, the “Mysterious Lady” at Scene 20 where the Latin reads, “UBI UNUS CLERICUS ET AELFGYVA” (Where a cleric and Ælfgyva). Why, you might wonder is Ælfgyva my favorite? It isn’t Ælfgyva per se, it’s the scene she’s in.

Because a chronicler of the time wrote that William had offered Harold one of his daughters in marriage in return for securing his place on the throne, many scholars believe she is the Mysterious Lady. Others suggest she may be Harold’s younger sister whose name is usually rendered as Ælfgifu. But I prefer the third explanation.

Some believe that it’s a sly depiction of a sex scandal of some sort. For this, I direct your attention to the naked man in the border below Ælfgyva. Not only is he well-endowed but the position of his arms is a mirror image of those of the cleric. (He’s not the only naked figure to appear in the margins but his body position does open a speculative door.)

If you can tear your eyes away from him now, you should know that the borders must, in some ways, embellish the story. In this panel you’ll notice two mythical animals to the naked man’s right. Elsewhere along its entirety, the lower border has depictions of at least four of Æsop’s fables. Scholars have identified The Fox and the Crow, The Wolf and the Lamb, The Wolf and the Crane, and The Wolf and the Kid.

The seven main events depicted on the Embroidery are (1) Edward the Confessor sending Harold, earl of Wessex, to inform William that he is the king’s preferred successor or, in some accounts, to have Harold swear allegiance to William. (Since Edward had no children, there could be no issue of primogeniture.)

(2) Harold is then shipwrecked in enemy territory but is rescued by William and, in return (3) assists him in a war against Brittany where he famously rescues Norman soldiers from the quicksand at Mont St Michel.

Harold swears an oath to William (4) but when Edward dies, Harold breaks his oath and claims the throne (5). In response, (6) the Normans build ships and prepare to invade England where (7) the two sides meet at the Battle of Hastings which ends with Harold dead and the Normans victorious.

A part of the Embroidery is missing. Most scholars suspect that it is the coronation of William the Conqueror.

Scene 57, depicting Harold’s death from an arrow in the eye is, perhaps, the most famous single scene on the work.

It’s also somewhat controversial. One needs to view the Embroidery as equal parts political and historical statement. In war, it’s generally the winners who write the history and, in this instance, the Normans had to, at the very least, reinforce the notion of William having the legitimate claim to the English throne. He did have to build ships and sail across La Manche to claim it, after all. The “Tapestry” could be their one-sided account.

Secondarily, there are some who believe that the figure with the arrow isn’t Harold. They point to the position of the standard bearers coupled with the report by William of Poitiers written sometime between 1071 and 1077. This is the most detailed and closely contemporaneous surviving account of the battle and he wrote simply that, “The king himself, his brothers, and the leading men of the kingdom had been killed.” Another contemporary writer, William of Jumièges wrote in 1070 that, “Harold, fighting in the front rank of his army, fell covered in deadly wounds.”

Additionally, there’s the matter of medieval symbolism and iconography. To the Normans, Harold was a perjurer. He had betrayed King Edward’s trust and broken the oath he’d sworn to William. In medieval times, such people were commonly depicted as dying from a stab in the eye.

Finally, there’s the question of restoration. The first known report of the ‘arrow in the eye’ story came in 1080 – three years after the original was completed. By the early twelfth century, that story had become the more settled version. It’s known that the Embroidery has had several restorations in its 950-year life and there’s rather convincing evidence that the arrow was added sometime in the 18th-century.

Viewing the (okay, I’ll break down and say it) Tapestry is a self-guided tour – as was our entire experience in Bayeux. Viewing the Tapestry, you’re given a headset for an audio guided tour that you can pause and rewind. However, even on the first of May the crowds are such that you are more likely to move through in the expected half hour making a limited number of stops. By the time we made it through, we were ready for lunch.