By tracing a bit of the history of Battle Creek, the arrival of Ellen and James White, and the establishment of the Seventh-Day Adventist church, we’ve laid the foundation for the work of John Harvey and Will Keith Kellogg. John Harvey was born into the small Adventist community near Battle Creek in 1852 – three years before Ellen and James White settled there. His younger brother Will was born in 1860. Ellen White’s teaching would play an outsized role in the lives of the Kellogg brothers.

Healthy Living – an Adventist credo.

In some ways one can view the SDA church as one of the more enlightened and certainly least dogmatic in western religious tradition. One key to that is the notion of “Present Truth”. It’s the notion that as worldly circumstances change, people can gain new insights into the timeless word of god. It’s an idea that might have arisen from the Great Disappointment – the failure of William Miller’s prediction of the date of the second coming and all of the Bible Conferences that followed.

Ellen White wrote, “The present truth, which is a test to the people of this generation, was not a test to the people of generations far back.” And her husband James added, “Present truth is present truth, and not future truth, and…the Word as a lamp shines brightly where we stand and not so plainly on the path in the distance.”

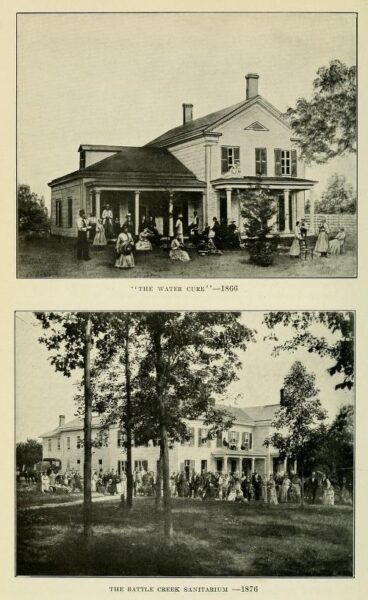

This openness to new information allowed the SDA Church to initiate expansive health reform efforts and healing ministries beginning in the 1860s. The first Adventist owned and operated medical institution,

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

known as the Western Health Reform Institute (also known as the Battle Creek Sanitarium) opened in Battle Creek in 1866. (Today there are nearly 2,500 Adventist owned or affiliated hospitals and non-acute sites.)

In addition to building organized healthcare institutions, Adventist health reform views included early support of the germ theory of disease, evidence of the benefits of a vegetarian diet, and abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs.

Ellen White was the prime mover in establishing a vegetarian diet. Adventists believe that Ellen White had the “gift of prophetic vision and inspiration” and it was just such a vision she had in 1863 that led her to proclaim that, “God’s people were urged to abstain from flesh food in general and from swine’s flesh in particular.”

She clarified this in her 1903 book Education writing, “Grains, fruits, nuts, and vegetables, in proper combination, contain all the elements of nutrition; and when properly prepared, they constitute the diet that best promotes both physical and mental strength.” Some outsiders might look at this level of discipline, and to a member of the SDA church say, “your style of life’s a drag” and that everybody needs a change and a chance to check out the new. However, the efficacy of the SDA lifestyle can’t be denied.

(The average lifespan in the U S is a bit over 82 years for women and 77 for men. For Seventh-Day Adventists, those ages increase by four years for women and seven years for men. While no single factor can be isolated, it was Dan Buettner who first identified five Blue Zones “where there are ten times as many centenarians as expected for a corresponding population size.” A mainly vegetarian diet and general abstention from alcohol were among the nine characteristics he cited that these zones share in common. The lone such area in the United States is in Loma Linda, California – not coincidentally home to a large SDA community.)

It was, in fact, another of White’s visions – this one on Christmas Day in 1865 – that led to creating the Western Health Reform Institute (WHRI). The Institute was intended to be a “water cure and vegetarian institution where a properly balanced God-fearing course of treatments could be made available not only to Adventists but to the public generally – and where they could not only be treated with sensible remedies but also taught how to take care of themselves and thus prevent sickness.”

With this background, I hope you now understand the first reason I consider a visit to Battle Creek’s Historic Adventist Village

important. But there’s yet another equally important reason.

And then along came the Kellogg brothers.

Because his parents believed in the imminent Second Coming of Christ they thus considered providing their children with a formal education unnecessary and neither John Harvey nor his younger brother Will Keith attended school past age eleven. However, John Harvey, came to the attention of the Whites while working for their printing house and it was here that Kellogg first became acquainted with Ellen White’s views of health and diet.

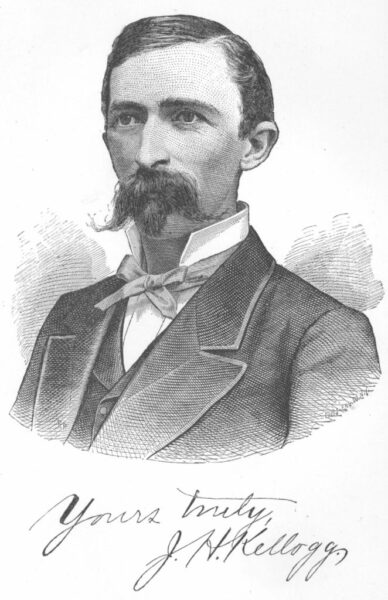

After enrolling him for a brief stint at the Michigan State Normal School, the Whites sent him to attend a six-month medical course at Russell Trall’s Hygieo-Therapeutic College in Florence Township, New Jersey. With the Whites continuing to serve as his patrons, Kellogg went on to attend Medical School at the University of Michigan and eventually earned his MD from Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1875.

[Photo of John Harvey Kellogg – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

He returned to Battle Creek where he became the director of WHRI in 1876. The next year he renamed it Battle Creek Medical Surgical Sanitarium colloquially known as the “San.”

The newly titled Doctor John Harvey Kellogg brought a rigorous application of both his medical education and the diet and health principles he’d learned from Ellen and James White. Beginning in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, people who came to the San were treated with a vegetarian diet based on balanced nutrition and had to abstain from alcohol, tobacco, and drugs – much as Ellen White would have mandated. Kellogg added to that the consumption of eight to ten glasses of water daily.

Doctor Kellogg went even further with his concept of complete wellness. Patients at his facility engaged in regular exercise both indoors and outside. Outdoor exercise was often supervised by the white suit wearing DoctorKellogg himself as part of a regimen that included as much fresh air and sunshine as possible and most days ended with the “hop on the top,” when, in what might be considered a precursor to aerobic modern exercise programs, patients marched to music on the San’s roof.

The San applied eight principal methods of treatment: hydrotherapy, phototherapy (for which he invented devices such as this one),

thermotherapy, electrotherapy, mechanotherapy (aka indoor exercise for which also he invented several devices),

dietetics, cold-air cure, and health training. Hydrotherapy was probably the primary form of treatment as more than 200 different methods were used.

Dyspepsia – a common term for upset stomach – was one of the most common ailments of this era and Kellogg not only believed that it could be treated through proper diet and exercise but also through some less conventional methods. For example, he considered cleanliness of the colon paramount because he believed humans, like some apes he had studied needed four to five daily bowel movements. Thus, enemas were a frequent part of his therapy and some of these could be extreme using machines capable of pumping as much as 15 quarts of water per minute into the rectum. If this proved insufficient, he prescribed a daily pint of yogurt. And if that failed, Kellogg substituted yogurt for water in the enema machines.

Still, guided by Ellen White’s principles, it was his implementation of their ideas around diet that were, perhaps, most innovative and influential. Working with his wife Ella Eaton Kellogg – a trained dietician, and his brother W K, the team developed new health foods in the Sanitarium’s experimental kitchen including grain-based coffee substitutes, Granola, Protose (a vegetarian meat substitute made from soy, peanuts, and wheat gluten), and Granose which was made of flaked, baked wheat kernels and is considered the first flaked cereal.

While Doctor Kellogg seems to be a bit of a visionary and a man ahead of his time, the rest of his story is a little darker. I’ll get to that in the next entry.