I don’t think one should visit Battle Creek without visiting the Adventist Village. Not only does this place play a substantial role in the development of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) but it’s also here that we’ll see the invention of what has become one of the great American breakfast items – flaked cereal – and the two are intricately intertwined. I’ll start by taking a brief historical look at SDA and, while I will endeavor to present it as objectively as possible, keep in mind that my perspective is that of an atheist and that view could color my interpretations.

But first a few words from Battle Creek.

Like the rest of Michigan, the area that’s now Battle Creek was once buried under miles of glacial ice. As the glacier advanced and retreated, it left some marks on the Earth in the way that glaciers do – creating moraines (comprised of glacial till or unsorted debris left behind) and lakes. Although elevation changes aren’t discernable from the Google Maps screenshot below, the hills of Battle Creek are moraines and Goguac Lake at the bottom of the map is a glacially carved lake.

The earliest indigenous people likely reached the area about 14,000 years ago with the more settled tribal people arriving in the last 10,000 – 11,000 years. Some 2,500 years BP, the Woodland culture that was responsible for the creation of many of the mounds that so fascinated me on my Mississippi River journey were the predominant group in this area of southern Michigan. They’d soon be joined by a group of Potawatomi migrating from the east. Of course, Europeans also migrated westward and the first European surveyors reached the area in 1825.

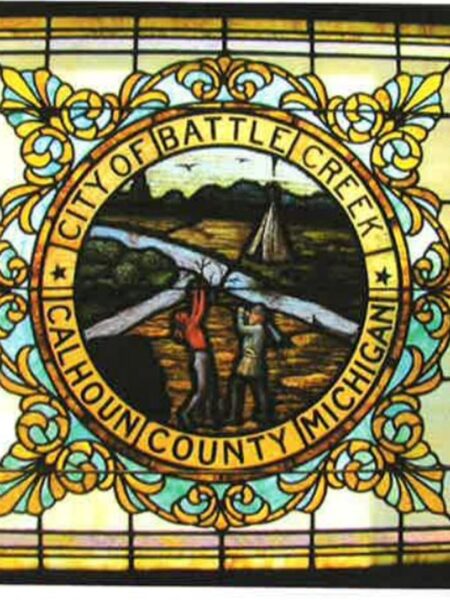

According to the Historical Society of Battle Creek, two Potawatomi approached the camp of those first surveyors asking for food. The exchange grew confrontational and the surveyors ended the exchange when at least one produced a rifle “subduing the Indians.” A later survey team recalled the initial report and bestowed the name Battle Creek on the site. The incident is memorialized in the city’s official seal.

[Photo from WWMT.]

In 1981 for mainly promotional purposes, the city replaced the somewhat offensive seal with a more benign appearing one

[Image from WBCK-FM.]

that’s used on city vehicles, business cards, and in press releases but not on official documents.

President Andrew Jackson, a forceful proponent of Indian “relocation,” signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. This act allowed the United States government to negotiate (e.g. force, coerce, or otherwise displace) with the tribes east of the Mississippi to relocate west of that river. When Michigan gained statehood in 1837, the native population there, including the Battle Creek Potawatomi, was subject to this act.

The Freedom City (At least after the Indians were gone).

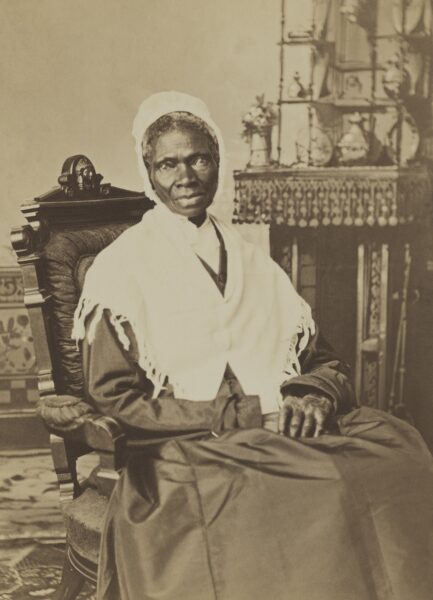

A group of Quakers were among the city’s earliest pioneers which, after spending time called Milton then Garnsey was incorporated in 1859 as Battle Creek. Erastus Hussey, who was a prominent abolitionist and who would later become mayor, lobbied unsuccessfully for the city to be called Waupakisca – a name he claimed was derived from a Native American term for the area. However, Hussey was successful in establishing Battle Creek as an important station on the so-called “Quaker Route” of the underground railroad. One estimate says that more than 1,000 escaped slaves passed through Battle Creek between 1840 and 1855. While many continued their journey eastward to Detroit and on to Canada, some chose to stay in Battle Creek perhaps drawn to the tolerant attitude of the Quakers that encouraged non-traditional perspectives. The most famous of those was likely Sojourner Truth

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

a peripatetic former slave who settled (as far as one could describe her as settling someplace) in southern Michigan in 1857, relocated to Battle Creek ten years later, and used it as her principal residence there until her death in 1883.

The tolerance of the Quakers for the unconventional would eventually attract members of a church that became known as

Seventh-day Adventists.

After the secular establishment of the nascent American government with its then relatively clear separation of church and state, the young United States saw a sequence of religious revivals spread across the country. Over a period of four decades beginning in 1790, this movement that has been deemed the Second Great Awakening fundamentally changed the character of America’s religious makeup. By 1800, Baptists and Evangelical Methodists were replacing Anglicans, Congregationalists, and Quakers as the preeminent religious sects.

Best known for its large tent revival meetings, this evangelical movement was characterized by an orientation that stressed personal piety, favored ordinary people over elites, and encouraged individual bible study. By emphasizing the idea of “free will”, the Second Great Awakening broke with the Calvinist traditions that had previously pervaded American religious life. While making the country more deeply Protestant, the movement also allowed for greater public roles for both women and African-Americans.

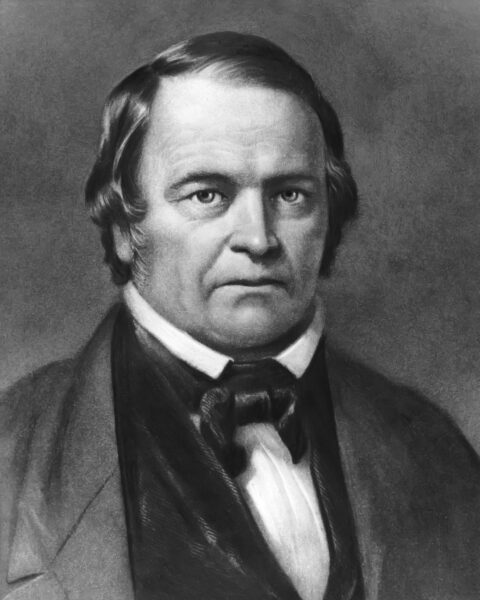

This movement also seeded the beginnings of the “Advent Movement” that can be traced to various smaller groups located mainly in the northeastern U S. In the 1830s, a farmer and military veteran named William Miller

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

drew a group of followers called Millerites when, based on his study and interpretation of two chapters in the book of Daniel, he predicted a literal Second Coming with a date of 22 October 1844. When (almost equally predictably) Christ didn’t reappear on that day, it became known to the Millerites as “The Great Disappointment”.

While this disappointment led some of Miller’s followers to reject his teachings and return to their previous churches, others doubled down in their studies in an effort to discern Miller’s miscalculation. Over the ensuing decade and a half, they organized “Bible Conferences” that eventually yielded six principles that would form the basis of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (though never successfully predicting or discovering the date of the Second Coming).

And then along came Ellen.

Like many of the preachers of the time, Miller was itinerant and took his scriptural interpretation from place to place. Attending a sermon he delivered in Portland, Maine in 1840, his lecture caught the ear of 13-year-old Ellen Harmon. Within a year, Ellen became a member of the Methodist Church. Six years later she would marry another former Millerite – the evangelist James White. It was with White and other similarly inclined groups that Ellen would play a critical role in officially establishing the SDA Church in 1863.

The term Seventh-day Adventist had been adopted in 1860 as different groups sometimes calling themselves the “Great Second Advent Movement” or “Sabbatarian Adventists” coalesced into a single church. One element of belief these groups held in common was that Saturday was the true Sabbath as it had been initially observed. (For Catholics and most subsequent Christian sects, the change from Saturday to Sunday was decreed by Roman Emperor Constantine in 321 CE.)

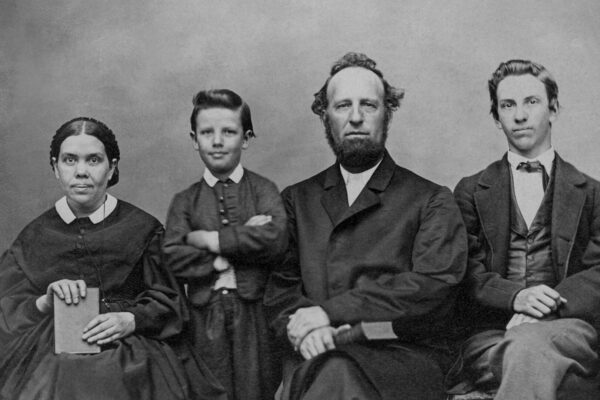

At the invitation of a small group of co-religionists, Ellen and James White settled in Battle Creek in 1855. Ellen was already quite well known having published in 1851 the first of two dozen books she authored. Once they settled in Battle Creek, the Whites, seen here with their two surviving children,

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

made the community the headquarters for their new denomination.

Under the guidance of the Whites, the SDA church established one of the largest printing and publishing houses in the United States and founded a health care facility which ranked at the time among the largest institutions of its kind in the world and that would become like a ribbon in the sky leading not only Adventists but people from every walk of life to Battle Creek.

And now the stage is set to tell the story of John Harvey and Will Keith Kellogg.