Although my personal travel in 2024 is far from over, today is the last full day of activities for the Road Scholar segment of the trip. Tomorrow, we’ll fly together to Sydney where we’ll share a final hotel dinner and spend the night at the Rydges Sydney Airport Hotel before flying off in different directions. Mine will be to Hobart but those are stories for later in this blog.

We started the day with a presentation from Hirani Kydd who

provided us with some basic information about the rainforest and its flora and fauna in advance of our visit to Kuranda – a small town accessible by the Kuranda Scenic Railway. (Kuranda although it’s in a rainforest, it’s not part of the Daintree World Heritage Rainforest which is 100km or so farther north and offers a very different experience.) This short 33km ride would be the final rail journey on this Great Australian Train Trek.

Construction of the railway began in 1877 and was a massive undertaking and a rather remarkable engineering achievement. Roughly 1500 men removed more than 2,300,000 cubic meters of earth, hand carving 15 tunnels, and building 55 bridges around 98 curves like this one.

The most famous of these is the curve called Horseshoe Bend. The train begins its 327 meter ascent at this 180° bend that has a radius of more than 100 meters. Here’s what that one looks like.

[From Cairns Australia]

And then the phone rang

(And misty memories of days gone by)

Not long after we boarded the train to Kuranda, our site coordinator’s phone rang. The call hadn’t come from a number she recognized but she answered it nevertheless. It was magic, alchemy, kismet, or whatever label you’d like to apply to an improbable occurrence. The person for whom S had left the confusing phone message was not only returning the call but, as it turns out, this person who had the same first initial and surname as my long ago traveling companion, was E’s mother! Of course she remembered how E had talked (I think fondly) about our time together. The younger E is living in Brisbane so I wouldn’t be seeing her on this trip since Brisbane wasn’t in my plans but I made arrangements to meet the older E and her husband for a beer when the group returned from Kuranda.

Even as I write this three months on, I’m still astonished at the random factors that had to align to make this event real. I had to be in Cairns. E’s mother (whose name I didn’t recall at the time) had to have the same first initial. She still had to have a landline phone. That phone needed to be listed. It needed to be listed not under her husband’s name, not under her name but under her initial. (Had it been listed under her full name, I likely wouldn’t have asked S to make that first call.) And then S had to answer her phone not only from an unrecognized number but when she and I were in close proximity. There’s still more to this story but you will have to get through the rest of the day first just as I did.

With that bit of reporting done, enjoy this random picture from the train of Barron Falls

to whet your appetite for some other photos from the train ride.

A dry day in the wet tropics

The rainforest at Kuranda, while not as biodiverse as the section at Daintree, shares many of its characteristics beginning with both being considered part of the Wet Tropics of Queensland – yet another UNESCO World Heritage Site. Here’s some of what we learned from Hirani.

The Wet Tropics of Queensland (WTQ) encompasses 894,420 hectares of mostly tropical rainforest stretching for 450km along the northeast coast of Australia. It’s not merely full of majestic landscapes and exceptional natural beauty but it’s extremely important for its rich and unique biodiversity and presents a record of the ecological and evolutionary processes that shaped the flora and fauna of Australia.

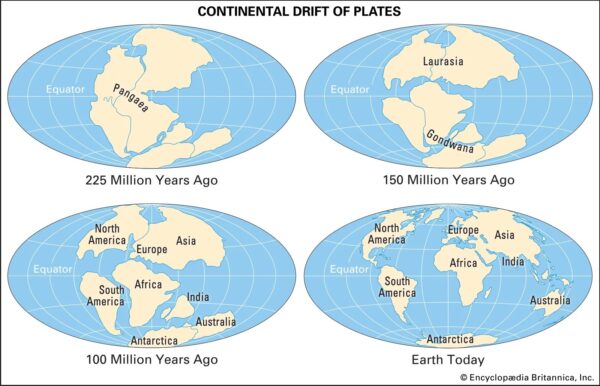

Recall that Australia was once part of Gondwana the supercontinent that once constituted a fifth of Earth’s surface. Much of Gondwana was a rainforest and between 50,000,000 and 100,000,000 MYA

[From Encyclopedia Britannica]

much of that rainforest covered much of Australia and part of Antarctica. Today, the WTQ contains relicts of that rainforest.

Unlike most other seasonal tropical evergreen equatorial forests, the WTQ has both a wet and a dry season. Together with its diverse terrain and steep gradients, many of its distinct features such as those seen at the juncture of the tropical rainforest with white sandy beaches and fringing offshore coral reefs (think of it as a land-based continuum of the Great Barrier Reef) result from this extremely high but seasonal rainfall. On its drier western margins tall open forests are also significant as part of an evolutionary continuum of rainforest and sclerophyll forests and the eucalypts that now dominate Australia’s landscape are believed to have radiated into still drier environments from these marginal areas.

In regard to its fauna, all of Australia’s unique marsupials and most of its other animals originated in rainforest ecosystems. (Recall the tree kangaroo we saw at the zoo in Sydney though this isn’t one that’s endemic to the WTQ.)

Many of their closest surviving members still live in the WTQ making it one of the most important living records of the history of marsupials and providing unique insight into evolutionary processes.

The WTQ supports exceptional diversity of both flora and fauna including:

- More than 3,000 vascular plant species of which 576 are endemic.

- 107 mammal species of which 11 are endemic.

- 368 bird species of which 11 are endemic.

- 113 reptilian species of which 24 are endemic.

- 51 species of amphibians of which 22 are endemic.

Among many emblematic species found in the WTQ is the flightless Australian cassowary, one of the largest birds in the world.

In an Australian context, the Wet Tropics covers less than 0.2% of Australia, but contains 30% of the marsupial species, 60% of bat species, 25% of rodent species, 40% of bird species, 30% of frog species, 20% of reptile species, 60% of butterfly species, 65% of fern species, 21% of cycad species, 37% of conifer species, 30% of orchid species and 18% of Australia’s vascular plant species.

Quite a special place indeed.

Hey. It LW1 from TT. Thanks for the help