A Yellowstone recap and leaving the park.

Wednesday morning as I once again defrosted my windows, I couldn’t help but think that in essentially what amounted to two days, I’d seen a lot of Yellowstone National Park while, at the same time, seeing very little of it. To recap, I’d seen Old Faithful erupt but I hadn’t seen any of the long duration eruptions such as Lone Star or Great Fountain Geysers. I’d seen the Grand Prismatic Hot Spring display its array of colors (albeit a bit muted because of the ashen sky) but missed the spectacular “inside out cave” formations of Mammoth Hot Springs.

Likewise, I’d seen the mud pots and paint pots of the lower geyser basin but not those of Lake Yellowstone. As for Lake Yellowstone, I’d skirted past it on more than one drive but the only lake I had an up close and personal encounter with was the tiny but unique Isa Lake. I’d had a nice hike along the south rim trail of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone but mainly bypassed the north rim which meant I’d gotten to the brink of the Upper Falls but not the Lower.

I experienced a buffalo jam in the Hayden Valley but other than seeing a large bison herd and a few elk in the Lamar Valley missed most of the wildlife – particularly the bears and wolves – that draw so many visitors to that part of the park. And, though it was time to leave, I hadn’t taken a hike of any significant distance let alone ascended a single mountain trail.

The drive from Canyon Village to the West Entrance – or in this case West Exit – was about 40 miles and would take me past Harlequin Lake. Since I’d gotten an earlier than expected start and faced another long day of driving, I decided I’d add the walk around the lake that I’d skipped yesterday. The trail is only about half a mile so even a complete circuit wouldn’t delay me very much. Even with my sweatshirt and windbreaker, the morning air was crisp enough to encourage a brisk pace around this lovely, yellow lily laden lake.

It was, I thought, a fitting farewell.

Earthquake Lake.

Although you cross the state line between Wyoming and Montana while still in the park, it’s not until you reach the town of West Yellowstone that you are formally welcomed to the Treasure State. (I know Montana is known as Big Sky Country but I’d seen very little bigness in its sky and its official nickname is the Treasure State.) Today’s route takes me north and west on U S 287 along Hegben Lake to the adjacent historic towns of Virginia City and Nevada City then on to Butte where I have a few stops planned before I end the day’s drive in Missoula.

(The trip actually started in Canyon Village but most of Yellowstone’s roads close in early November. I’m writing this in December and the date functionality in Google Maps doesn’t allow multiple stops or route changes so I had to “fool” it which is why I appear to start at a very specific address in West Yellowstone. Mapquest couldn’t even be bothered to find Canyon Village in Yellowstone and while AAA’s travel planner allowed me to choose a summertime travel date, for some reason, it would only take me from Canyon Village to West Yellowstone but then refused to plan a route beyond that point. After 20 minutes, I finally settled for the compromise you see above.)

I don’t recall where I read about or who told me the story of Earthquake Lake (sometimes called Quake Lake) but since it wasn’t much of a detour, I thought it would be an interesting place to drive past. Once again, with the benefit of hindsight, I would have extended my stop to include the Visitor Center and to take more photos but that option wouldn’t become clear until I reached Virginia City and Nevada City. (I hope at some point the lesson that I should take advantage of what’s in front of me and let the future take care of itself sinks in and I release this type of regret – fleeting as it might be.)

Earthquake Lake was born on 17 August 1959 when the strongest recorded temblor to strike Montana – an estimated 7.5 on the Richter Scale – shook the ground in and around the Gallatin National Forest. The earthquake was strong enough to be felt more than 300 miles away in Salt Lake City. The lake reached maturity just three weeks later when the dammed Madison River now formed a lake that was 160-170 feet deep.

One of the two main actors playing a role in the formation of Earthquake Lake and the human tragedy that accompanied it, was the Hebgen Dam (seen at the pinpoint in the satellite photo below). The dam, an 85-foot-tall concrete-core earthen embankment dam, was built across the Madison River by the Montana Power Company in 1914 to store and regulate water for other downstream reservoirs and hydroelectric power plants.

The production’s co-star, so to speak, was the 80-million-ton landslide (about a billion cubic feet) that collapsed nearly half of Sheep Mountain into the river and formed a landslide dam on the Madison River roughly seven or eight miles upstream from the Hebgen Dam. You see, it wasn’t simply this newly formed natural dam that created the lake. The presence of the dam downstream and the lack of an outlet for the flow caused a massive seiche (pronounced saysh).

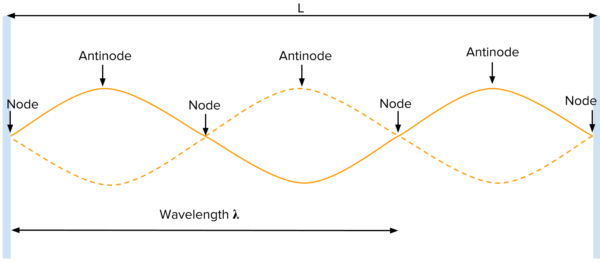

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a seiche is, “a standing wave in which the largest vertical oscillations are at each end of a body of water with very small oscillations at the “node,” or center point, of the wave. Standing waves can form in any enclosed or semi-enclosed body of water, from a massive lake to a small coffee cup.”

Those of us who remember our high school physics might recall that a standing wave (sometimes called a stationary wave) is a combination of two waves moving in opposite directions, each having the same amplitude and frequency.

[Wave chart from Khan Academy].

The phenomenon is the result of interference—that is, when waves are superimposed, their energies are either added together or canceled out. When the two waves are in phase, they combine their energy in a process called constructive interference. Conversely, waves with the same amplitude in different directions cancel each other’s energy in the process called destructive interference. In the case of waves moving in the same direction, interference produces a traveling wave; for oppositely moving waves, interference produces an oscillating wave fixed in space.

Seiches with long wavelengths are quite common but the longer the wavelength, the less energy the waves have to combine. This means many seiches can pass completely unnoticed not only to the human eye but even to boaters on a lake who are experiencing a long wave seiche. (Think of the wavelengths of light. To get tan, you need exposure to short frequency, high energy ultraviolet {UV} light. Because infrared waves are long frequency waves, you could plop yourself down under a bank of infrared heat lamps and, while you might get to feeling a little toasty, those long, low energy waves won’t get you tan. Sunscreen protects your skin because it blocks UVB rays. The higher the SPF, the greater the percentage of UV rays it blocks.)

On the other hand, when there’s a lot of energy put into the system, it has to go somewhere. A 7.5 Richter Scale earthquake alone would generate enough energy to create a huge seiche that would make it the equivalent of a lake bound tsunami. Add in the atmospheric energy generated by an 80-million-ton landslide that happened so quickly it generated near hurricane force winds and you have a recipe for disaster. In this instance, the human disaster was the deaths of 28 people camping near the river that became the lake.

One bit of evidence of the valley before the lake formed can be seen in the bleached, bone-white tops of dead trees that still break its surface in places

and in the still quite bare mountainside.

This informational sign provides some comparative views.