Before we set off to visit the birthplace of Josip Broz who ruled Yugoslavia for more than three decades under his better-known moniker of Tito, our group will make a brief and previously unplanned stop in Zagreb. I hinted at this in a previous entry about Zagreb and it’s the stop for which I take at least partial credit.

Those of you who have followed me on some of my previous trips know of my predilection for visiting cemeteries. As I researched the places we’d visit on this tour, I read about cemeteries in two cities that I thought not only merited, but required a visit. One was ┼Įale Central Cemetery in Ljubljana the other was Mirogoj Cemetery in Zagreb. (The proper pronunciations are Zhah-lay and Meer-oh-goy.)

I knew from our chats┬Ābefore the trip that Judy was another cemetery┬Āenthusiast and I think others in the group came to think they might enjoy seeing this famous place after they heard me pestering Damir about it for days. At some point yesterday, heŌĆÖd suggested that we start our day half an hour earlier than originally scheduled so we could stop at Mirogoj┬Āon the way to Kumrovec and the group gave their consent. (It was this decision and consensus that allowed me the freedom to roam about the Lower Town. Otherwise, I would have gone to Mirogoj on my own.)

Before I go much further, I’ll share a pair of photos with you. This first of Mirogoj from the air is from the website Like Croatia. The photo gives some idea of the breadth of the colonnades and a good look at the chapel but no sense of the cemetery’s real size – which is about three kilometers long and five kilometers wide.

And this one of the main entrance is from the travel site Uguest.

(I will note that Pat was kind enough to share some of her photos with me and the one below of a colonnade interior is hers.)

In 1876, the celebrated Croatian linguist, writer, and politician Ljudevit Gaj donated a plot of land on which to begin construction of the cemetery and, after his death, the city bought Gaj’s estate to expand it. (Gaj was prominent in the Illyrian Movement of the 19th century that sought to build a foundation for cultural and linguistic unification of all Southern Slavs and to create what amounted to a distinct Croatian federation of political units with coequal rights within Austro-Hungary. Gaj remains so revered that, according to Wikipedia, 211 roads in Croatia bear his name.)

As I hope you can see from the two┬Āphotos above, the cemetery is, perhaps, even more of an open-air gallery celebrating art and architecture than others of its kind.

The principal architect of the cemetery was Hermann Boll├® whose work you’ve previously seen in the ─Éakovo and Zagreb Cathedrals. Boll├®’s initial plan was to have the cemetery’s layout reflect the design of the Lower Town of 19th century Zagreb. However, he often altered those plans and building the cemetery proved no small task. Construction of the main building, arcades and cupolas began in 1879 and continued for another half century. Boll├® is among the thousands interred in Mirogoj.

Walk through the cemetery and you will find areas designed by other architects, and sculptures by Croatian artists such as Ivan Mestrovic, Antun Augustincic, Dusan Damonja, and Edo Murtic. Of course you can find the graves of scores of famous Croatians (there’s a rather large site for Franjo Tu─æman (thanks again, Pat)

and thousands of the not so famous with generations of families sharing the same site.

and thousands of the not so famous with generations of families sharing the same site.

Another of Mirogoj’s unique traits is that believers from nearly every religion practiced in Croatia – Catholic, Orthodox, Muslim, Jewish, Protestant, and Latter Day Saints are buried there with each religion having its own section. Even atheists are buried in this massive place. You can find a number of fine photos here if you’re interested in seeing more.

Ti-Totalling.

I promise not to fill space with minutia about Tito’s life and his rise to power but his influence pervades more than a half century and, I’d say, the man from Kumrovec still casts a shadow over all the newly independent Balkan nations. I hope that learning who Tito was and how he became that person will help sharpen the clarity of the picture of Balkan history I’ve tried to present. Let’s get started.

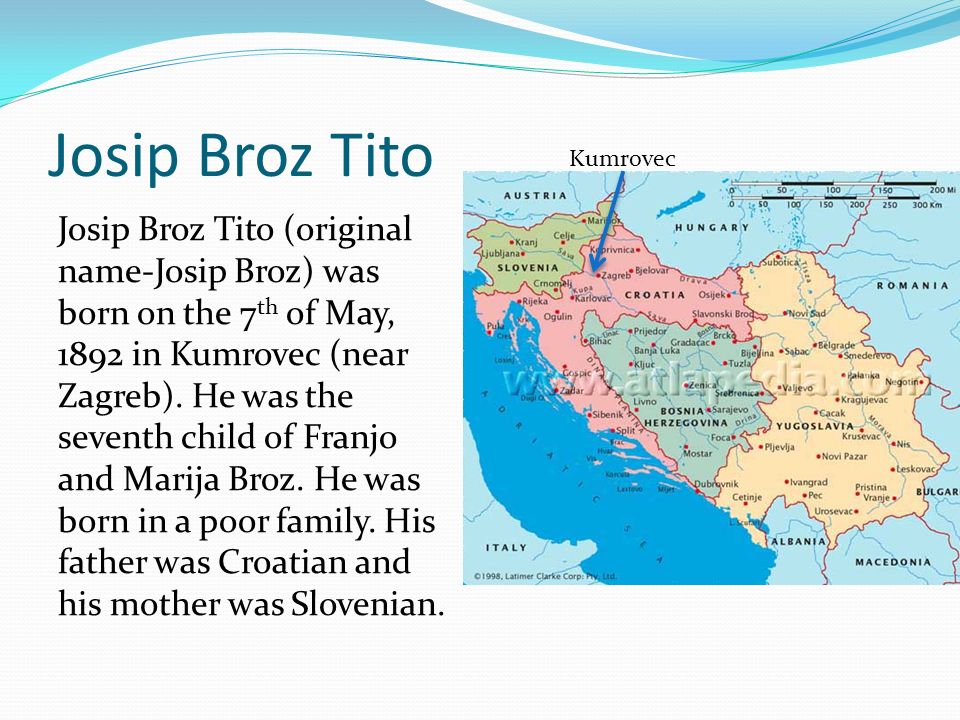

Here’s a wonderful slide I found while searching for a map to help you see the location of Kumrovec:

The tip of the arrow should be a bit closer to Slovenia. Kumrovec is about 60 kilometers northeast of Zagreb and less than a kilometer from the Slovenian border in the Croatian region of Zagorje. That proximity of his birthplace to the two countries clarifies the slide’s note that one of his parents was Croatian and the other Slovenian. You should keep this in mind as we look at Tito’s life and politics.

The part of Kumrovec we visited is an open-air museum. Those of you who read about my Scandinavian trip in 2015 might recall my visit to another open-air museum – ┬ĀSkansen in Stockholm. While not nearly as old or diverse as Skansen, the museum at Kumrovec is, in some ways similar and some important ways quite different. It’s similar in its mission of preserving and presenting a representation of traditional village life. The main differences are that Skansen covers a broad range of Nordic traditions while Kumrovec is limited to the specific time and place of Tito’s youth. Everything on display at Skansen, while original, has been relocated to the site. Conversely, families who have lived for generations in the homes in the Kumrovec museum still live there making it both a museum and a living village.

When┬ĀJosip Broz┬Āwas born in 1892, Kumrovec was part of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. (Recall that the Compromise of 1867 established the joined┬ĀKingdom of Croatia-Slavonia as a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire within the Hungarian sphere of influence.) The adult Josip liked to parade his humble upbringing which was both true and untrue.

At the time of his birth, his father’s family had lived in Kumrovec since the 16th century and his father owned a farm of about four hectares that he’d inherited. The home, while modest, was probably quite nice by the standards of the day.

(Please remember that from this point forward, I shot none of the included photos. With apologies to those whose photos I use, I won’t provide attribution but I am asserting fair use. I will remove any photos at the copyright owner’s request.)

Unfortunately, Josip’s father Franjo wasn’t particularly adept at the business of farming and it was as much this ineptitude as any other factor that contributed to the humility of Broz’s childhood. Until he reached school age, young Josip lived with his maternal┬Āgrandparents 16 kilometers away in Podsreda in Slovenia where he learned to speak Slovene and play the piano. The first in his family to become literate, Josip was not exactly a brilliant student. He failed the second grade but eventually graduated from primary school in 1905 at age 13. Later in life he’d prove to be a much better student of military strategy, politics,┬Āand human nature.

While he was still┬Āin school, a number of villages in the Zagorje region staged a revolt against high Hungarian taxes. The spirit of the people who clashed with armed police and Hungarian soldiers – four of whom were forcefully billeted in the Broz house – left a┬Ādeep impression on the 11-year-old boy.

He worked in agriculture for two years after leaving school before moving to Sisak – a town about 100 kilometers south of Kumrovec. Josip eventually convinced a Czech locksmith, Nikola Karas, to apprentice him for three years. After completing his apprenticeship in 1910, he moved to Zagreb where he joined the Metal Workers’ Union and the Social-Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia. But he faced a crucial detour before he could fully establish his locksmithing career. WeŌĆÖll pick up that story in the next post.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

I love cemeteries I once visited a couple of cemeteries on South Carolina (sorry I have long lost the names). One was full of amazing sculptures. The other was near the rice museum and was from one of the most deadly hurricanes to hit that area in in the early 1800s (if I am remembering correctly). The aftermath was so severe it ended the production of rice in that area and it often decimated entire families I was very moving to read the various tombstones and see extensive extended families who all perished at the same time.

I think cemeteries can reveal aspects of a place that aren’t always obvious.