Oh, that’s Richelieu. Tell me more.

We need now to take a quick, if brief, temporal step back to Henri IV. Recall that in 1572 Henri married his second cousin Marguerite de Valois who was a de’ Medici. After 27 childless years, Henri had the marriage annulled and, deeply in debt to her father, married Marie (Maria) in December 1600 – another member of the powerful Italian de’ Medici family. (Despite his professed conversion to Catholicism {because,as he famously said, “Paris is well worth a mass.”}, the relatively tolerant Henri was, in fact a Huguenot, and for much of his reign, at war with the Catholic League {The dark side of “Le Bon” perhaps?}. To prosecute the war, he had borrowed nearly 2,000,000 écus from Marie’s father Francesco and his marriage effectively canceled the debt.) Unlike her relative, Marie was quite fertile. Apparently her fertility was the only use Henri had for her in what is reported to have been an otherwise loveless and even contentious marriage. In the 10 years before Henri’s murder, the couple had six children – the eldest of whom was Louis who would become Louis XIII.

Marie was crowned Queen of France on 13 May 1610. Coincidentally or not, Henri was assassinated the next day and Marie was confirmed as regent during nine-year-old Louis’ minority. Never politically astute, the earliest of Marie’s actions as regent included the dismissal of the Duc de Sully and abandoning the long held French policy of opposing the Habsburgs. (Marie’s mother, Joanna was from that line.) Her time as regent was marked by constant political intrigues.

In some ways, those intrigues began to end in 1616 when she admitted Armand Jean du Plessis to her royal council making him Secretary of State and giving him responsibility over foreign affairs. A year later Louis, who was several years into his legal authority, began to assert his power as king. He nullified his mother’s policy toward the Habsburgs and eventually banished her from the court. He also came to rely more and more on du Plessis. In 1622, Louis nominated du Plessis for Cardinal which was granted by Pope Gregory XV and, in 1629, Louis would confer on him the title by which he would be best known and remembered, the Duc du Richelieu.

[Portrait of Richelieu by Philippe de Champaigne – Wikimedia – Public Domain.]

Richelieu was in fact, though not in name, the most powerful of Louis’ ministers. He wielded so much power that some historians believe that the most notable aspect of the reign of Louis XIII is his subservience to the Cardinal who was both ruthless and, at the same time, exceptionally politically savvy. Although the Académie française – the oldest of the five académies of the Institut de France (we’ve previously encountered one of the others – the Académie des Beaux-Arts) was established during the reign of Louis XIII, credit for its founding is generally given to Richelieu.

One of Richelieu’s principal policy goals was to centralize power in the monarchy. He and Louis exercised what is known as the “royal monopoly of force” – systematically destroying the castles of any member of the nobility who rebelled against him, condemning dueling and the personal possession of lethal weapons, and the maintenance of private armies. The state was, in essence, asserting a monopoly on large scale violence. The importance of having Richelieu as one’s friend and ally was clear to everyone.

Thus, as the Duc du Sully built and occupied the house at number seven and Richelieu took up residence on the square at number 21, other members of Louis’ court saw where they needed to reside to be in proximity to power. This is when the square truly became the Place Royale. And Richelieu used it to his advantage reportedly satisfying his lust with every noble lady who lived in the square’s pavilions.

Of course, no telling of the story of the Place Royale would be complete without a mention of Marion de Lorme.

[Image of Marion De Lorme as portrayed in Victor Hugo’s play – Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

The famous courtesan occupied the pavilion at number 11 hosting a salon while at the same time she might or might not have been secretly married to the Marquis de Cinq-Mars who was executed in 1642. By all accounts, Marion certainly enjoyed her life fully and her lovers and benefactors were reputed to include the wit and writer Charles de St Evremond, George Villiers the 2nd Duke of Buckingham, Prince de Condé and, of course, Cardinal Richelieu.

Hard times come to the Place.

I found two similar reports on how the square came to be renamed the Place de Vosges. One states that the département of Vosges was the first to pay taxes to the new government after the 1789 Revolution. The other states that it was the first to pay a tax called by Napoléon in 1799 to support the campaigns of his Revolutionary Army. In either case, there’s little doubt that the name acknowledges the département in the eastern part of France.

By the end of the 17th century, neither the Place Royale nor le Marais were the fashionable areas they had been at the time of their construction. The new place to see and be seen was Saint-Germain-des-Prés on the Left Bank so le Marais and the Place des Vosges became a bit neglected like Louis’ banished mother, Marie.

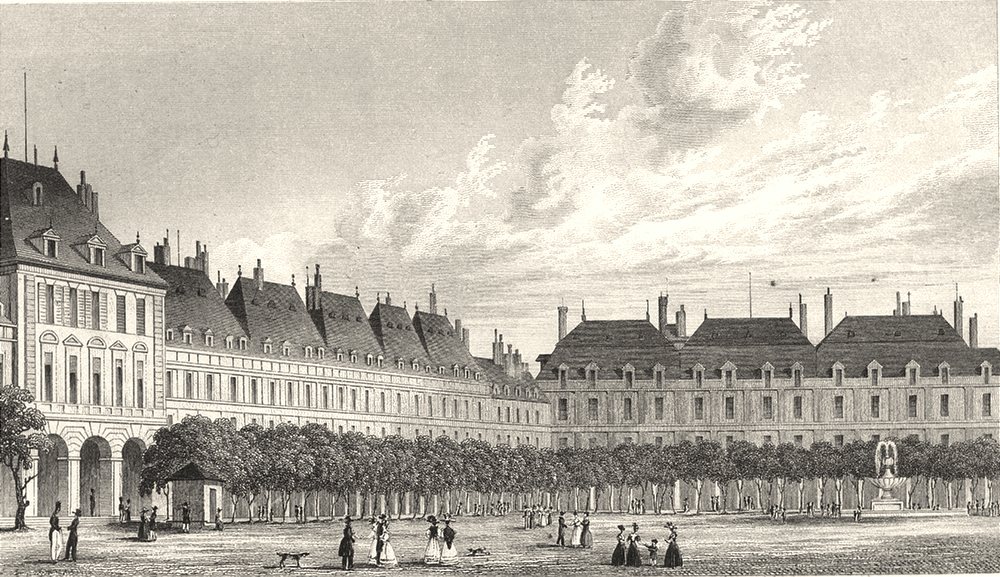

Still, while it might not have been as prestigious as it had once been, in the nineteenth century, the novelist Alphonse Daudet and the poet Théophile Gautier lived on the square as did perhaps it’s most renowned resident of the time – the writer Victor Hugo. Hugo lived at number 6, then known as the Hôtel de Rohan, and he might have looked out on a scene like the one in this 1831 print (from antiquemapsandprints).

The Maison de Victor Hugo is now a writer’s house museum.

However, the vicissitudes of time took their toll on the Place des Vosges. Downie writes,

…the 1789-to-Second World War of Place des Vosges history is a chronicle of corrosive decline. Factories sprang up in courtyards. Pavilions were dismembered, their aristocratic interiors junked (luckily a few were preserved and remounted at the nearby Museé Carnavalet, Paris’s city history museum). If vast sums hadn’t been spent on the square in recent decades it probably would have collapsed.

But collapse it did not and today, the Place des Vosges is again among the most desirable addresses in Paris. In 2015, a 72 square meter flat on the fifth floor (sixth by American counting) was listed on the website parisperfect for € 1,279,000. Historically, residents lived on the second floor known as the étage noble. When David published Paris, Paris in 2005 he asserted, “Étage noble flats are the most valuable at up to seven million dollars.”

As for the 21st-century appearance of the Place des Vosges,

from the colonnaded arcades to the brick facades of the pavilions (or in some cases trompe-l’oeil plaster applied to wood if the resident couldn’t afford real brickwork)

they all remain true to the vision of Henri IV – Henri le Bon.