Too soon for some history about Tucson?

In my first post about this trip, I wrote a bit of a cautionary travel tale based, in part, on my experiences on this last full travel day. The lesson is, “Be prepared.” Although you might be driving on numbered U S routes, in the American west, you’ll likely drive scores of miles on two lane roads with little or no traffic and long stretches with no place to stop for gas, food, or a toilet.

After learning both the park and museum in Blanding were closed Sundays, I chose to stop in Sedona for lunch rather than driving east to Four Corners or west to Antelope Canyon – alternatives I’d considered.

As we set out together on this drive, it strikes me that Sedona is a long haul of about 300 miles and nearly five hours. With my only stop coming at the first gas station I reached and nothing in the way of photos to break the monotony, I’ll pass the time by sharing some of Tucson’s history that I haven’t yet reported. Skip ahead if you prefer.

What’s in a name?

On my drive from Tucson to Organ Pipe National Monument, I passed through the Tohono O’odham Nation. It’s likely that Tucson’s name is linguistically derived from their native tongue. As you drive around the city, this mountain, with its distinguishing ‘A’ will periodically pop into view. (The ‘A’ was originally placed there after a 7-6 win by the University of Arizona football team in 1914.) Today, most people refer to it as A Mountain.

[Photo from Wikipedia By Bill Morrow – CC BY 2.0].

It wasn’t always thus. Before it was called A Mountain, it was called Sentinel Peak and had been named for the remains of a fortified Indian watchtower on its top. Before the Euro-Americans began calling it Sentinal peak, it had another name, Cuk Ṣon (pronounced Tshook-shawn) an O’odham phrase meaning “at the base of the black hill” – because the mountain, located on the west side of the Santa Cruz River, is a black volcanic formation. Over time, Cuk Ṣon became Too-sahn. (This likely explains the curious spelling, too).

How old is it?

There’s a Wikipedia page called “Timeline of Tucson, Arizona”. This is its initial entry:

1732 – Mission San Xavier del Bac founded by Jesuits near present-day Tucson.

Archaeological evidence places the earliest Hohokam – likely ancestors of the Tohono O’odham – settlements in the area sometime circa 2,100 BCE making them among the first of the nomadic tribes to establish more permanent settlements. Of course, since they provided no written record, it’s perfectly reasonable (sarcasm implied) for us to ignore the 3,800 years of history between these initial settlements and the arrival of the Spanish in the 18th century. Sadly, I have little choice but to be complicit in this. (By the way, even the mission founding date is questionable. I found sources that date the mission to 1700.)

Some of the archaeological evidence that signals the shift from nomadic to a more settled agricultural lifestyle, is the development of ceramics and pottery and traces of vast irrigation canal systems by the Hohokam. There’s no doubt they dwelled in the valley long before the Europeans arrived.

But even the Spanish presence in the area long predates the establishment of the Mission San Xavier del Bac. In 1539, Father Marcos de Niza claimed Arizona for Spain. A year later, during his search for the seven cities of gold, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado did the same though neither put any settlement there.

The Mission San Xavier del Bac is a bit outside the current city limits on the San Xavier Indian Reservation. Since it played an important role in the European colonization of the region, and, because it required only a minimal detour, I stopped by to snap a few pictures en route to the airport Monday morning.

I have only a few exterior pictures because I lacked the time and the inclination to go inside.

Presiding over the Presidio.

Some decades after the original mission’s establishment, a fellow with the adopted name Hugo Oconor led a company of Spanish forces to the valley along the banks of the Santa Cruz River. Born in Dublin as Hugh O’Connor, he joined the volunteers of Aragon as a young man, rose to the title of major, and became Hugo Oconor in the process.

Oconor was a Spanish Military governor in Northern Mexico when he selected a site to construct a military fort, the Presidio San Augustίn del Tucsón, that overlooked the floodplain of the Santa Cruz. This Spanish son of Ireland authorized the Presidio’s construction in 1775. It began a year later, was completed in 1783, and earned Oconor the distinction of being called Tuscon’s founder.

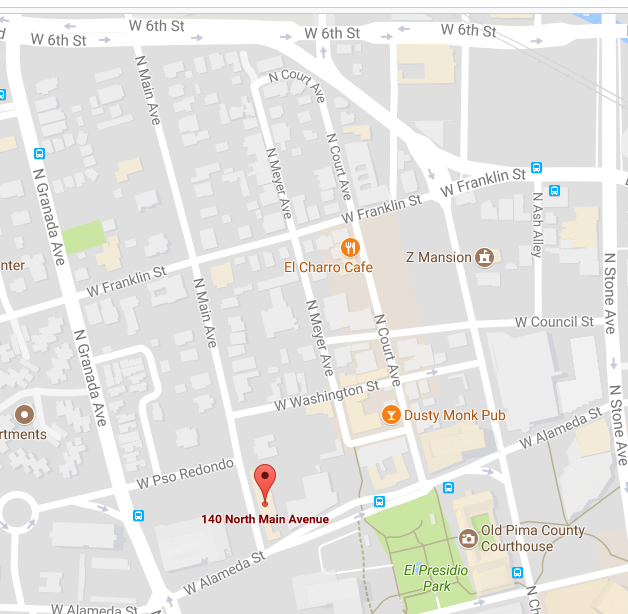

In today’s Tucson, El Presidio is on the national register as a historic district but, except for an archaeological excavation that revealed the foundation of the corner of the original Presidio, none of the original building remains. However, within the district, shown here,

you can find the small El Presidio Park, the Old Pima County Courthouse, two museums including the Tucson Museum of Art, and a reconstructed 20-foot-tall adobe tower called a torreon. I walked the three-quarters of a mile from the Downtown Clifton Motel – where I’d spend the final night of the trip – to the courthouse but much of the area was hidden behind construction fencing and again, I didn’t take any pictures. I expected none of these places to be open because it was Sunday evening so I didn’t venture any farther into the neighborhood. Neither did I seek out anyplace associated with that daughter of Tucson and my teenaged crush – Linda Ronstadt.

Red rocks at lunch.

As late as Sunday morning, I was considering intermediate stops at either Four Corners, Antelope Canyon, or Sedona. I’d read enough mixed reviews about Four Corners that, although it’s the only place in the US where four states intersect, it just didn’t seem worth the hour or two it would add to the drive. That left me to choose between Antelope Canyon and Sedona.

I’d seen jaw-dropping photos of Antelope Canyon. However, while it would only have added an hour and a half to the drive, it would have also added at least another two hours for a guided canyon tour. I think I would have needed to start very early and I simply couldn’t muster the right level of enthusiasm.

While it might seem like I opted for Sedona by default, that’s not the whole story. When I left the east coast for Arizona, I really didn’t have much intention of visiting there though it seems that nearly everyone who visits Arizona includes Sedona. During the trip, however, so many people suggested visiting the town that it grew ever more present in my mind. The trip from Blanding needed five hours so I timed my departure to arrive at lunchtime.

Here’s a little background:

The town was named for Sedona Arabella Miller Schnebly (1877–1950) who was the wife of Theodore Schnebly, the city’s first postmaster. Sedona’s mother, Amanda Miller, claimed to have made the name up because “it sounded pretty.”

Sedona’s greatest claim to fame is its red rocks. These are part of a rock layer known as the Schnebly Hill Formation which is a thick layer of red-orange-colored sandstone that’s found only in this area. This sandstone, a member of the Supai Group, was deposited during the Permian Period.

I didn’t seek out any movie locations during my visit there but I certainly could have. Sedona has hosted more than sixty Hollywood productions including Broken Arrow (1950 version with Jimmy Stewart), The Rounders with Glenn Ford and Henry Fonda, and National Lampoon’s Vacation.

I had to drive through much of the town before I reached the Javelina Cantina where I’d decided to have lunch. I’d hoped for an outdoor table with a view something like this:

Unfortunately, the al fresco dining area was full so I stayed inside. I made a small mistake when I greeted my waiter in Spanish that sounded authentic enough to him that it became our language of interaction. The truth is, that while I retain strong phonetic Spanish, my ability to understand and communicate in that tongue has diminished significantly since my peak conversational usage nearly 40 years ago. He’d say something and most of the time I simply smiled and nodded politely. (And by the way, I am aware of the irony of having lunch at a place named for a javelina – aka a skunk pig).

While I can certainly imagine someone traveling north from Phoenix being absolutely enthralled by Sedona, I was less impressed. Perhaps I had, indeed, become a bit jaded from having driven for nearly two weeks through scenery of comparable beauty. Or it could be that I needed to be in Sedona when the sun sets and the vivid red of the rocks for which the town is so famous is more intense. But I’d seen it, had my lunch, and that was enough. On to Tucson.