A museum is born.

In May 1791, the Assembly declared that the Louvre would be “a place for bringing together monuments of all the sciences and arts”. They nationalized the royal collection when the revolutionaries captured Louis XVI on 10 August 1792. One year later to the day, the government held a symbolic opening of its new museum. By October, the general public had free accessibility three days per week.

However, life as a museum wasn’t always smooth and easy sailing for the Louvre. It ultimately survived the rough tides that accompanied the rise and fall of Napoléon Bonarparte, the Bourbon restoration, the 1871 Paris Commune, and two World Wars. The collection remained intact through the German occupation during World War II largely due to the foresight of Jacques Jaujard then the director of the French Museée Nationaux (National Museums).

On 25 August 1939, Jaujard ordered the Louvre to close for three days for “repairs.” During those so-called repairs, more than 200 empty trucks arrived at the museum. Each truck left carrying at least nine wooden cases. The trucks deposited most of their cargo at the Château de Chambord. When the calendar turned to 14 June 1940 and the streets of Paris looked like this,

the Louvre looked more like this.One last controversy. I M Pei and the Pyramid.

I think it’s inarguable that an adherence to and reverence for tradition and resistance to change is perhaps more deeply embedded and a more essential element of the Parisian (and perhaps the French) character than nearly any comparable society. One might view the French reluctance to change as personified by the 40-person council, the Académie française, whose sole purpose is regulating the French language. Unlike English, a language that happily incorporates global forms of expression, part of the job of the Académie française is limiting the invasion of foreign words and phrases.

As I wrote in a previous post, when Charles Eiffel proposed the construction of his now iconic tower, the group of French intellectuals calling themselves the Committee of Three Hundred didn’t merely protest the proposed tower, they published a scathing letter in a Paris daily newspaper calling it the “useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower” envisioning that “all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream.”

In 1983, François Mitterrand, the first Socialist president of France in nearly half a century, broke with the French tradition of holding design competitions for public projects when he personally and privately contacted I M Pei to offer him a commission to modernize the Louvre. The prospect ahead of Pei was prodigious and he took several months to consider the offer before accepting it.

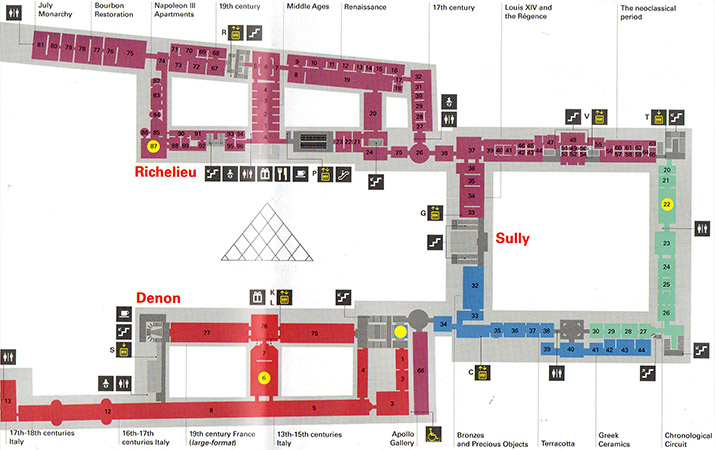

The buildings that comprised one of the most celebrated art museums in the world had fallen into a state of disrepair. The museum had only two public toilets and the art was presented so incoherently that visitors often wandered about lost in the maze of corridors. Additionally, because the galleries constituted the bulk of the space, curators had little or no place to manage, store, and care for the artwork. Equally problematic, the French Minister of Finance had claimed the Richelieu Wing for his department’s offices and refused to allow any public access.

After Pei accepted the commission, he first had to survive the public outrage engendered by Mitterrand’s unilateral decision. But that was merely outrage stage one. When he revealed the Pyramid he proposed to build in the Cour Napoléon (Napoleon Court) the French daily Le Figaro led a campaign against the design calling it “atrocious.” Even the New York Times (which probably had no business inserting its opinions on Parisian architecture) railed against it in 1985 writing that it was, “an architectural joke, an eyesore, an anachronistic intrusion of Egyptian death symbolism in the middle of Paris, and a megalomaniacal folly imposed by Mister Mitterrand.”

Eiffel’s contract with Paris required the city to allow the structure to stand for 20 years and, of course, over time, his eponymous tower didn’t merely overcome that initial wave of obstreperous resistance but became emblematic of the city. It should come as no surprise then that in 1999, on the tenth anniversary of the completion of the Pyramide du Louvre, the same Le Figaro that had once called it atrocious, published a supplement celebrating the Pyramid’s genius.

For some, the pyramid at the Louvre rivals the Eiffel Tower and Sacré Coeur as defining elements of the Parisian landscape. Jean Luc Martinez, the current director of the Louvre, once described the Pyramid as, “the modern symbol of the museum. It is an icon on the same level as the Louvre’s most revered artworks the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace.”

I should note that you might have heard an urban legend that the Pyramid has 666 glass panes – the so-called Number of the Beast. Of course, this is untrue. As Wikipedia points out,

Elementary arithmetic allows for easy counting of the panes: each of the three sides of the pyramid without an entrance has 18 triangular panes and 17 rows of rhombic ones arranged in a triangle, thus giving rhombic panes (171 panes total). The side with the entrance has 11 panes fewer (9 rhombic, 2 triangular), so the whole pyramid consists of rhombi and triangles, 673 panes total.

If you’re interested in reading more about the Pyramid, this story from Architect Magazine has some fascinating details and revelations.

Before we leave the Cour Napoléon, I need to turn my attention to one other structure – the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel. So named because it stands in the Place du Carrousel that marks the eastern end of the Tuilleries Garden. (Carrousel was a type of military dressage that carries forward today in competitions and is called a “military drill.” Louis XIV held such a display there in 1662 thus conferring the name on the square.)

This monument holds a certain sentimental interest for me that has nothing to do with its architectural style (Corinthian), its size (19 meters tall – less than half the height of its more famous counterpart the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile at the western end of the Champs-Élysées), or the quadriga of Peace that adorns the entablement.

No, my attachment to this Arc de Triomphe stems from the 1979 movie A Little Romance – one of my favorites. (Note: In 2024 I learned from David Downie’s book The Paris, Paris Timeline, that the horses atop the Arc which was built in 1806 at the behest of Napoléon 1 – were stolen from the Cathedral of Saint Mark in Venice.) The movie stars 14-year-old Diane Lane appearing in her first film, 72-year-old Sir Lauence Olivier appearing in one of his last, and features Arthur Hill and Sally Kellerman. The plot is a story of first love between Lane’s character Lauren and her French crush Daniel who is equally infatuated with Lauren. After circumstances force Lauren to break their first date when they agreed to meet at the Gare Saint-Lazare (train station) because neither knows where the other lives, Lauren’s excitable, “terminally dense” friend Natalie comes to tell Daniel that Lauren can’t meet him but asks if they can reschedule the date and the location. Daniel agrees and tells Natalie where to have Lauren meet him:

Daniel: Tell her the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in front of the Louvre.

Natalie: The Arc de Triomphe.

Daniel: No! No! Not the big one at the Champs-Élysées. The small one in front of the Louvre.

Natalie (turning away.): In front of the Louvre. (Turning back and giggling.) Oh, that’s the museum Louvre, right?

There was, at that time, no Pyramid.