Broadly speaking, there are three ways to approach tourism in a city with as many diverse attractions as Paris. On one hand you can choose the highly organized option – sweating out a list of places to visit and sights to see prepared in advance of your arrival. On the other hand, you can drop anchor with no plan whatsoever and make spontaneous choices based more on inspiration than perspiration. This freewheeling approach can be simultaneously challenging and facile. The third way is to try blending the two.

Make random and spontaneous choices and you can feel satisfied by day’s end because you will have been someplace or seen something that interested you in the moment. The challenge is that there’s so much to see and do that you try to either cram too much into a day and see things only superficially or you’re so selective, so intent on seeing things thoroughly that you end your limited time there with some regret over the list of places you didn’t visit. After a busy Friday and Saturday Pat and I faced this very dilemma for Sunday and Monday. We’d seen a lot, missed a lot, had no plan in place for either day, and only two days left to see so much and miss so much more.

Thus it was, that during our break Saturday between our visit to l’Orangerie and dinner, I reserved a spot for a free walking tour that started outside Notre Dame at 11:00 Sunday. My thought was that in the worst-case scenario we’d learn nothing new but would have had some time to consider how to fill the afternoon and in the best case we’d hit one of those, “Why didn’t we think of that,” moments. It turned out to be closer to the former.

Since the tour started rather late in the morning, we indulged ourselves with a very hearty late breakfast at a café called Le Lutétia on the Île Saint-Louis. Hearty breakfasts aren’t the norm in France and while I could be satisfied with a croissant, juice and tea, I’d also grown somewhat accustomed to that large and sumptuous breakfast buffet on the ship. I indulged in a cheese omelet and too much bread – but, oh, those baguettes! It was a perfectly fine omelet with its flavor enhanced by the view.

Clock and Castle.

La plus vieille horloge de Paris.

We met our guide in front of Notre Dame and while it’s possible that Maeva identified the nearby statue of Charlemagne on our first walking tour two weeks ago, I don’t recall her doing so. The guide on this tour did so immediately thus providing a small ‘something new’ moment. Better still, when we walked past the Conciergerie, she stopped at the corner of boulevard du Palais and quai de l’Horloge and had us look up. If you remember the day we spent in Rouen where we saw le Grand Horloge there you won’t be surprised by what we saw when we did.

While the guides and guidebook will tell you that this is the oldest public clock in Paris, I think that description needs some clarification. It’s the location of the oldest public clock in the city but the clock itself is an enhanced and restored version of the original.

The 47-meter tower is the tallest in the Conciergerie and was built sometime in the mid-14th century. Originally it housed a bell that was rung to mark important times of the day such as shop openings and bar closings. (I hope you recall that the guards still use bells to mark the closing of Père-Lachaise thus carrying on this tradition.) In 1370, an engineer from Lorraine named Henri de Vic received a royal commission from Charles V to replace the bell with a clock. (As I noted in a previous post, the Conciergerie was originally constructed in the ninth century as a fortress and over time successive kings turned it into a palace. It had been the Parisian home to French kings since the tenth century and, when Philippe II hosted Richard I of England it cemented Paris as the French capital.) It was now the clock that rang out the day’s important hours.

Germain Pilon, a French Renaissance sculptor, gave the clock its first enhancement when he replaced the original face with a gilded, multicolored face framed by allegorical statues representing Law and Justice. Severely damaged during the French Revolution, the clock was then restored in 1849 by Pierre-Basile Lepaute (the nephew of Jean-André Lepaute who’d had the run in with Beaumarchais) and it had a more recent restoration in 2012. Nevertheless, it is, in most ways, the oldest public clock in Paris.

Le Louvre.

Today, of course, the Louvre is famed as one of the world’s great museums and with gallery space of 72,735 square meters it is also the world’s largest single museum. The aerial view below from Wikipedia provides some sense of its size. (The Hermitage in Saint Petersburg is second at just more than 66,800 square meters. Of course, both are dwarfed by the total square footage of Washington DC’s Smithsonian Institution but it is a complex of 20 museum buildings plus the National Zoo that are in and around Washington as well as the Cooper-Hewitt Museum and Heye Center in New York City. The National Gallery of Art is neither part of the Smithsonian nor the largest art museum in the United States. That title belongs to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art which is 58,820 square meters.)

But it wasn’t always thus. Although we only visited the courtyards and not the museum itself, I’m going to enhance the information provided on our tour and tell you how the Louvre began life as a fortress that then transformed into a royal palace before becoming the museum we know today.

When in Paris, French kings were still living in the Palais de la Cité (Conciergerie) when Philippe Auguste (Philippe II and, if you recall, the first to call himself King of France rather than King of the Franks) decided he’d join Richard I of England on the Third Crusade. However, he realized the need to build a wall to protect the city that had now become the de facto capital of his realm. (And, of course, you know that part of Philippe’s wall still stands just a few meters from the flat where Pat and I stayed.)

Philippe anticipated that one of the weakest sections of his wall would be the point where it met the Seine on the Right Bank just west of the Île de la Cité. That spot, he thought, demanded not just a wall but a fortress as well. Thus, the Louvre was born. His engineers designed a square fortress protected by a moat and equipped with circular defensive towers at each corner as well as in the middle of its sides. They also built a main tower with its own moat in the center of the courtyard.

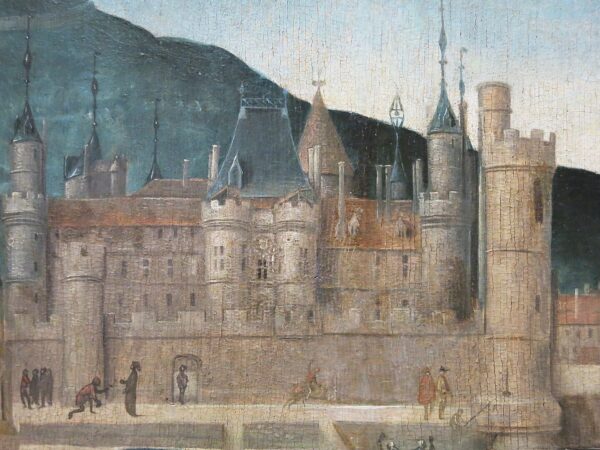

This enlarged view from the 15th century painting Pieta de Saint-Germain-des-Prés provides a sense of its appearance (though likely one additions begun by Louis IX).

[Detail from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

Called the Grosse Tour (Great Tower), the central cylindrical keep served not only as a royal treasury and armory but at times it was also a prison for royal enemies. (For example, Philippe imprisoned Ferdinand, count of Flanders there for thirteen years after the latter’s defeat at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214.)

Although it was originally constructed on the edge of the city, over time a more densely packed urban district arose around the fortress slowly eroding its defensive imperative. Louis IX, (aka Saint Louis) was, perhaps, the earliest king to use the structure more as a residence than as a fort. He built a large, pillared hall in the château basement that can still be seen today. This began the Louvre’s first transformation that I’ll examine in the next post.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

The Obelisk, which have been ideally placed in the middle of the Place de la Concorde since 1836, is part of the strange geometrical layouts and alignments along the Historical Axis, evoking the symbols of Ancient Egypt . In 1988, this great Egyptian landmark was joined by another pharaoh-related structure along the Historical Axis: the modern Glass Pyramid in the Louvre, evoking the Great Pyramid of Giza.