To connect north with south

(Building bridges for the living)

Now that we’ve experienced the creation of Sydney Harbour we can look at the construction of the Harbour Bridge. Although the notion of a harbor crossing arose as early as 1815, more than a century would pass before the laying of the foundation stone for one of the southern abutments on 26 March 1925. (Sticklers might say that construction began when the first sod marking the start of work on the approaches to the bridge was turned in July 1923.)

The first person in authority to entertain the idea of a bridge across Sydney Harbour could well have been Lachlan Macquarie whom you met in a previous post. Francis Greenway, an architect by trade who had been convicted of forgery and sentenced to 14 years transportation approached Macquarie in 1815 with a proposal to build a bridge just three years after his conviction and arrival in Australia.

Although Macquarie eventually appointed Greenway as the government’s first civil architect and he went on to build St Matthew’s Church, St James’ Church, and the Hyde Park Barracks, the plans to build a bridge across the harbor never reached fruition. The factors impeding building a bridge likely included the cost and technical difficulty involved in building bridges over large tidal expanses of water such as Sydney Harbour and the scarcity of materials such as durable masonry and cast iron.

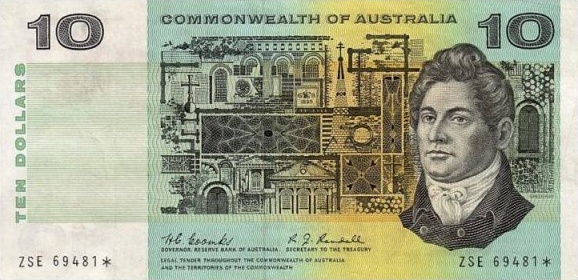

Continual personality clashes between Greenway and Macquarie led to the former’s firing in 1822. Greenway died in poverty in 1837. An ironic coda to his life played out when his depiction appeared on the first ten dollar note issued by the Bank of Australia in 1968.

[Australia 10 dollar note – Public Domain]

It’s likely that Greenway is the only convicted forger whose likeness ever appeared on a country’s official currency.

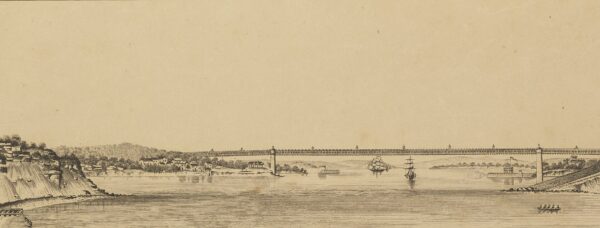

The idea for a bridge appeared off and on throughout the 19th century. Two years after New South Wales became the first Australian colony to gain self-government, Peter R Henderson, an engineer submitted what is considered by most historians to be the first serious proposal to construct a bridge across Sydney Harbour. His design, seen below, spanned the harbor from Dawes Point on the south to Milson’s point on the north side which is the location of the bridge today.

[Peter Henderson bridge design from Wikipedia – Public Domain]

John Job Crew Bradfield, a founder of the Sydney University Engineering Society in 1895, is often described as the ‘father’ of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. In 1900, a competition had been held to design a bridge from Dawes Point on the south to Milson’s point but there had been no follow through.

Over a three-month period in 1912, Bradfield submitted two design proposals for the Harbour Bridge. The first was for a suspension bridge but it was soon followed by a cantilever design. In 1913, the same year he was appointed chief engineer for metropolitan railway construction, the NSW Parliament accepted his plan to construct a cantilever bridge. Plans got underway but the outbreak of World War I saw the proposal tabled as a war economy measure.

[John Job Crew Bradfield from Wikipedia – Public Domain]

A bridge just far enough

Bradfield had ambitious plans not only for the bridge but for all of Sydney and in 1922 Sydney’s parliament passed the Harbour Bridge Act. After an international competition that ended on 16 January 1924, Bradford and his team recommended a two-hinged steel arch with abutment towers designed by Dorman, Long & Co of Middlesbrough, England. The company was in the process of constructing the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle which had a design proposal

[Image from Time Out]

that will look familiar with those who have seen Sydney’s bridge.

Construction continued apace beginning with the demolition of 802 buildings on both sides of the harbor. More than 1600 men worked on the bridge over the nine-year construction period. Sixteen of them died. Requiring 39000 tons of steel, arch construction began on 26 October 1928. Cantilevering two half arches from each side of the harbor, the two sides met on 19 August 1930. The deck could now be built and it was completed in June 1931 followed by road, rail, water, drainage and gas lines, and ultimately load testing completing one of the great engineering feats of the first third of the 20th century. The bridge officially opened on 19 March 1932. However, by that time 52,000 school children had already crossed the bridge in a series of what officials termed ‘school days’. Perhaps you’ll be interested in watching this less than scintillating video.

A bit of controversy followed Bradfield regarding his claim to have designed the bridge. Although Bradfield had submitted the original plan, it was Dorman Long’s consulting engineer, Ralph Freeman who oversaw the detail of the bridge design. Consulting architects Sir John Burnet and Partners were responsible for the aesthetics of the span, in particular the granite-faced tower pylons that served no structural purpose. These were among the factors that led Dorman Long to threaten to sue the government if it erected a plaque naming Bradfield as the designer.

My photos of and from the bridge are here.

Sydney on The Rocks

When we completed our walk across the bridge some of us chose to climb the 200 stairs to the top of the southeast pylon to experience the grand views such as this one

from 87 meters above sea level as well as visiting the museum that displays exhibits about the construction and history of the bridge. From there our group moved on to the area called The Rocks.

Before the arrival of the First Fleet, the Gadigal people had custody of the land they called Tallawoladah. Although the aboriginal people of Australia might not have used this classification, within a western worldview, the Gadigal people might be considered a clan within the Eora nation. In a broad sense it was the Eora who first encountered the Berewaigal or Europeans. Sharing the fate of many Indigenous People around the world, perhaps as many as 80% of Australia’s Indigenous People died of introduced diseases to which they had no immunity. Some First People died in conflicts and still others may have died simply as a result of being separated from the land to which they belonged. (The relationship the Aboriginal people of Australia have with the land they inhabit is a subtle and difficult concept that’s as far outside the way more familiar cultures view their relationship with the world we inhabit and is one to which I’ll return at other points in this journal. However, once grasped, the reader should be able to understand why simply moving a person from their land might cause or at least contribute to their death.)

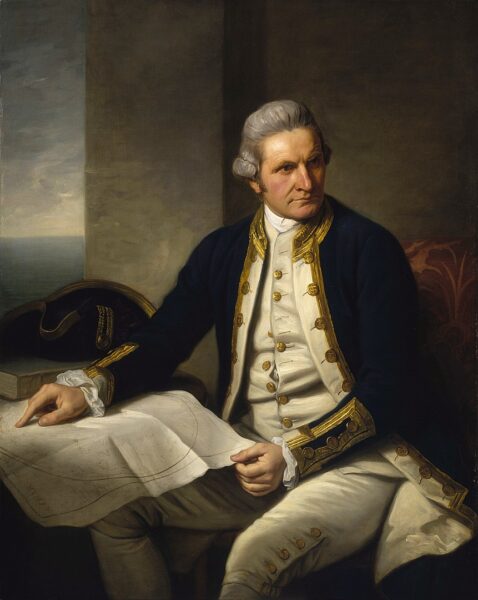

Before proceeding much further, we need to briefly examine the concept of terra nullius – a doctrine the British used and misused to overwhelm the continent and displace the Indigenous People. Its initial application to Australia occurred in 1770 when Captain James Cook

[From WIkipedia – Public Domain – Painting by Nathaniel Dance Holland]

found his way to Botany Bay and claimed possession of the east coast of the continent for Great Britain. Although Cook had some contact with the Eora People, he was either unable to recognize or, more likely, deliberately chose not to recognize their humanity, their technology, and their societal structure. Thus, Cook categorized the land as “terra nullius” a Latin term meaning land of no one.

At this time in European history, the principle of terra nullius was one of three major tenets providing for the occupation of a foreign land – two of which had to be followed if the land was inhabited. Thus, an inhabited country could be invaded and, if the native inhabitants were defeated in a war, the victor (in this instance Britain) could claim ownership and possession of the territory. In such an instance, however, the rights of the conquered people had to be respected and settled through treaty negotiation.

A second possibility was to recognize the Indigenous inhabitants, request permission to use the land, or even negotiate its purchase. As with the principle above, land theft wasn’t permitted and Indigenous rights had to be recognized.

If a country was uninhabited, it could be declared terra nullius and the “discoverer” could settle the land and take ownership thereof. By not recognizing the existence of the Indigenous inhabitants of Australia, Britain could simply occupy the land and displace the “non-existent” people without war, purchase, or treaty. And this they did.

In 1835, nearly half a century after the arrival of the First Fleet, Richard Bourke issued a proclamation formally implementing the principle of terra nullius in Australian law marking the official basis for British settlement. The law stood for 157 years until it was overturned by the Mabo Decision in 1992.