Coca leaves in the 21st century.

Recall that soon after Evo Morales was elected as the country’s first indigenous president, Bolivia adopted a new Constitution in 2009. This is Article 384:

The State shall protect native and ancestral coca as cultural patrimony, a renewable natural resource of Bolivia’s biodiversity, and as a factor of social cohesion; in its natural state it is not a narcotic. Its revaluing, production, commercialization, and industrialization shall be regulated by law.

This placed Bolivia in conflict with the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs which had cited the coca plant as a Schedule One drug. The 1962 Bulletin on Narcotics of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs stated,

after a definite transitional period, all non-medical use of narcotic drugs, such as opium smoking, opium eating, consumption of cannabis (hashish, marijuana) and chewing of coca leaves, will be outlawed everywhere. This is a goal which workers in international narcotics control all over the world have striven to achieve for half a century.

Article 23 of the Single Convention also requires countries to set up a “government agency” to take charge of controlling the licit cultivation of opium poppy for medicines, and Article 26 says that the same system of controls should also be applied to licit coca cultivation adding that, “The Parties shall so far as possible enforce the uprooting of all coca bushes which grow wild. They shall destroy the coca bushes if illegally cultivated.”

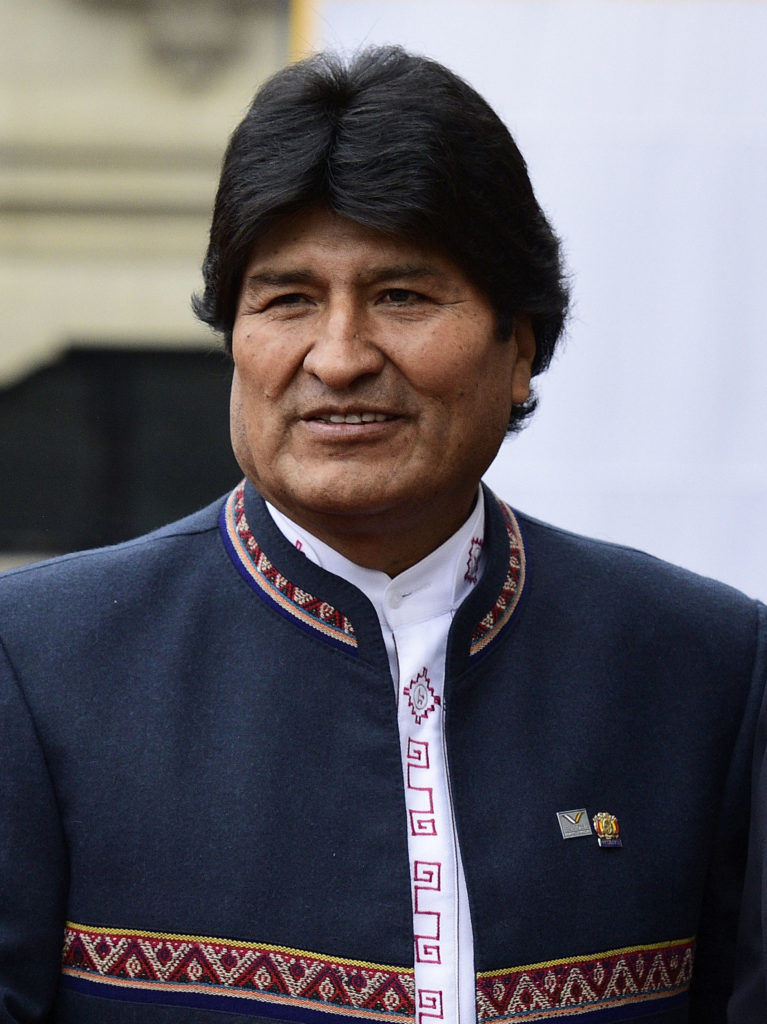

[Photo of Evo Morales from Wikipedia By Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores from Perú – Presidentes del Perú y Bolivia inauguran Encuentro Presidencial y III Gabinete Binacional Perú-Bolivia, CC BY-SA 2.0.]

Morales had risen to power through the cocalero movement and his rise had been inadvertently abetted by the U S war on drugs. (Cocaleros are the coca leaf growers of Bolivia and Peru.)

In 1986, the Bolivian government headed by Víctor Paz Estenssoro implemented the Plan Trienal de Lucha Contra el Narcotráfico (Three Year plan to Fight Drug Trafficking) largely at the behest of the United States. One of its stated aims was ending coca production. Initially, the plan sought to encourage voluntary eradication and crop substitution. It went on to stipulate that any illegal coca that remained in place after the period of voluntary eradication would be subject to forced eradication and it designated the Cochabamba region (where most coca was grown) as a military zone.

It was clear from the outset that the Bolivian government was working closely with the U S in these eradication efforts. All the cocaleros (both legal and illegal) noticed the heavy American presence be it in the form of U S intelligence, weapons, or helicopters.

[Photo of soldiers destroying a coca field from World Politics Review.]

The cocaleros began to mobilize and one managed to consolidate his position of leadership. That one man was Evo Morales. Some in Bolivia believe that Morales would not exist as the figure he is today had it not been for the resistance to the United States presence in the coca producing areas.

Morales was able to turn Bolivia’s cocalero social movement into a political one. Running as the leader of the Movement for Socialism Party, Morales articulated an agenda with broad demands that transcended the differences between historically competing sectors such as legal and illegal cocaleros, rural and urban, and peasant and labor. As a result, many in Bolivia have seen his extended (possibly unconstitutionally extended) government as one that belongs to the people. Having Morales as president signifies to Bolivians that the originarios – the peasants, the indigenous, the excluded – are at last governing themselves.

In an attempt to obtain legal recognition for traditional use, Peru and Bolivia negotiated paragraph 2 of Article 14 into the 1988 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, stipulating that measures to eradicate illicit cultivation and illicit demand “should take due account of traditional licit use, where there is historic evidence of such use.” (Conversely, and perhaps perversely, the 1988 Convention also provided new mechanisms to enforce the 1961 Single Convention.)

In 1994 the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) – the monitoring body for the implementation of the UN international drug control conventions – mentioned that drinking of coca tea (and I regularly drank several cups a day) “which is considered harmless and legal in several countries in South America, is an illegal activity under the provisions of both the 1961 Convention and the 1988 Convention, though that was not the intention of the plenipotentiary conferences that adopted those conventions.” The INCB went on to retract this position in 2007 but such locally and culturally licit coca use continues in both Bolivia and Peru.

More than just tradition.

[Sharing coca leaves. Image from National Geographic.]

Yes, cocaine and its attendant evils can be extracted from the leaves of the coca plant. But there is much more to this maligned plant than its stimulating alkaloids. Keep in mind that the Spaniards of the 16th century noted only salutary effects – better focus, the ability to tolerate longer periods of work and the like – on the native coca chewers. They exploited this but mentioned none of the deleterious effects we see in cocaine addicts even though these people had been chewing coca for thousands of years. (Only after the Spaniards altered the fundamental relationship between the people and the plant and European science concentrated the extraction of a single alkaloid do we see these negative effects.)

Studies performed at the Bolivian Institute of Biology at Altitude have shown that, possibly due to the increase of catecholamine, the chewing of coca leaves has a stimulating effect on respiratory centers and acts on hemoglobin to inhibit platelet aggregation. Both of these physiological effects can be a critical aid to people living at high altitudes and in the Andes many people live more than 4,000 meters above sea level. At these altitudes, the chronic lack of oxygen is considered the major cause of erythrocytosis – a blood disease in which the body, struggling to overcome the lack of oxygen, produces increasing amounts of red cells. This increases blood viscosity, circulatory difficulties, and the associated risks of thrombosis – the formation of blood clots within blood vessels.

In addition to its benefits in helping people adjust to altitude, coca is an important source of vitamins and minerals particularly phosphorous and vitamin B complex. D0ct0r Jorge Hurtado Gumicio, who founded the Coca Museum in La Paz, sets out the nutritional values per 100 grams of coca leaf in this table:

| Calories Proteins (gr) Fats Carbohydrates Calcium (mg) Phosphor (mg) Iron (mg) Vitamin A (iu) Vitamin B1 (mg) Vitamin PP (mg) Vitamin C (mg) Vitamin B2 (mg) |

305 19.9 3.3 44.3 1749 637 26.8 10.000 0.58 3.7 1.4 1.73 |

Earlier I described the process of akullikuy – the way the natives ingest the coca leaf. This consumption technique slowly ruptures the vegetal cells and bathes them in saliva before they are fully ingested. This makes it impossible to dissolve and absorb only one chemical (the cocaine alkaloid) as some have argued. The capacity of the human digestive tract to absorb the proteins contained in the leaf remains unstudied but even without the full absorption of protein, the plant has clear nutritive value. (It seems to me that, at a minimum, further study is clearly warranted.)

Perhaps a day will come when the benefit of ingesting coca properly will outweigh and obliterate the demand for the isolated alkaloid and we will all be able to reap the benefits of proper coca leaf ingestion.

If you can’t visit the museum and you’re interested in learning more, you can try the museum’s website.