Sixteenth century lobbyists.

The so-called coca problem was formally addressed in the Councils of Lima in 1552 and 1569. Two groups pressed for either the complete elimination or at least the limitation of coca use in the First Council of Lima – the prohibitionists and the so-called humanitarians. The prohibitionists called coca “a useless and pernicious leaf” and also claimed that the indigenous belief in its physical effects was an “illusion of the Devil.” The humanitarians cited the conditions under which the camayos were forced to work but placed the blame more on the plant than the overseers.

Ultimately, the bishops recommended that the indigenous population be discouraged only from making their offerings with coca, maize, water, and any other thing asserting that this step would help their conversion efforts. That argument won the day in the First Council. The bishops did not, at that time, pose any objection to coca’s ingestion.

[Map from Peru Info.]

The situation had changed by the time of the Second Council of Lima in 1569. The debate over coca use had become more heated and the prohibitionist views had gained strength. By this time, however, the coca trade involved approximately two thousand Spaniards throughout the Viceroyalty of Peru and was generating income of more than one million pesos annually. (As the above map shows, the Viceroyalty was a Spanish administrative area centered in Lima that controlled most of Spanish-ruled South America)

The coca growers hired Juan de Matienzo to press their interests not only to the Archbishop but, more crucially, to King Phillip II. Rather than being the fruit of the devil as the prohibitionists described it, Matienzo portrayed it as a gift from god that provided stamina and nourishment to the indigenous population. He was blunt in his assessment that “…if coca was taken away, the Indians would not go to Potosi, they would not work, and they would not extract silver.” Banning coca would economically devastate the viceroyalty. King Philip resolved the matter by formally authorizing coca production.

The more things change.

Although cocaine is the most well-known and problematic of the alkaloids found in coca leaves, they contain at least a dozen other alkaloid compounds each with varying degrees of pharmacological effect and toxicity.

Photo of a cup of coca tea.

In 1855 a German chemist, Friedrich Gaedcke, isolated some of those alkaloids from the coca leaf and one in particular drew considerable scrutiny over the ensuing decades. That alkaloid was, of course, cocaine. (It fell to a PhD student named Albert Niemann to perfect a purification process for extracting cocaine in 1860.)

In 1884, Karl Koller, a German doctor seeking to prove cocaine’s anesthetic efficacy, applied a solution of cocaine hydrochloride to his own eye before pricking it with pins. His findings, presented to the Heidelberg Ophthalmological Society, sparked a surge in cocaine research in the U S and Europe that gradually led to its widespread use on both continents not only as a surgical anesthetic but as a treatment for alcoholism, depression, and exhaustion.

By the last decade of the 19th century, the United States had become the main consumer of both coca and cocaine products – mostly in beverages and elixirs – but also in topical anesthetics used for toothaches, hemorrhoids, and corns. Cocaine infused products were heavily promoted as treatments for alcoholism, opium and tobacco addiction, and as a cure for asthma. In some instances, pure cocaine was marketed directly to consumers.

Over time, the problematic side effects of cocaine use began to manifest and articles started appearing in medical journals and other publications detailing those negative impacts. These reports spawned a backlash of opposition against cocaine led by physicians, journalists, and boards of health. Their single target was the pharmaceutical industry which they charged with irresponsibly marketing cocaine and they demanded reforms in its sales. The federal government finally became involved through the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 which attempted to regulate the sale and use of cocaine and required the proper labeling of products containing cocaine.

The birth of the Real Thing.

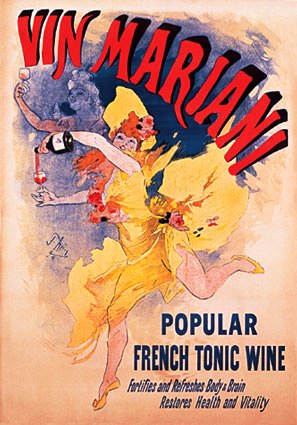

A mere three years after Niemann perfected his method for isolating the cocaine alkaloid, Angelo Mariani, a French chemist, created a drink he called Vin Mariani whose blend of Bordeaux wine with coca leaves became popular in both Europe and the United States. However, because coca infused drinks were already popular in the United States, the version Mariani exported contained 20 percent more cocaine per liter than his domestic fermentation.

[Poster for Vin Mariani by Jules Chéret – from Wikipedia Public Domain.]

Heavily promoted for its ability to increase energy and uplift one’s mood, Mariani was able to obtain testimonials from prominent people on both sides of the Atlantic. Not only did Émile Zola and Ulysses S Grant appear in advertisements for Vin Mariani but so did Charles Gounod, two popes (Leo XIII and Saint Pius X), and Henri Rochefort among others. Thomas Edison claimed it helped him stay awake longer and John Philip Sousa wrote his own testimonial,

When worn out or after a long rehearsal or a performance, I find nothing so helpful as a glass of Vin Mariani. To brain workers and those who expend a great deal of nervous force it is invaluable.

In 1885, an Atlanta druggist named John Pemberton began marketing his own version of Vin Mariani called Pemberton’s French Wine Coca. Within a year, however, both the city of Atlanta and Fulton County passed prohibition legislation. Undismayed, Pemberton developed a non-alcoholic version of his drink that featured carbonated water and the main ingredient that had differentiated his wine from Mariani’s – an extract from the African kola nut that provided a jolt of caffeine as well. He named his new product for its two stimulants. Thus was born Coca-Cola.

Next, it’s time to take a look at the modern war on cocaine and some recent attempts at the plant’s reclamation.