A few more highlights.

If I were to attempt to recount in any depth the breadth of information that David and Alison provided, it would tax my memory far beyond its limited capacity and your patience far beyond the general stress I put on it with each of these posts. (I will, however, have a bit more to say about le Marais when we reach the Place des Vosges.) Instead, I’ll touch upon some highlights of our walk through the fourth and look in depth at two more stops in the Marais. I’ve provided some limited information in some of the photo captions.

Before proceeding, I feel compelled to note that I think the four of us felt an almost immediate sympathetic connection of shared interests and world views. Curiously, we spent much of the morning walking in distinct pairs – David and I in one set and Pat and Alison the other. (By the end of the day, I think the women, had they thought about it, would have felt relieved that we’d formed these pairings naturally. David and I discovered our shared passion for puns quite early on and I think that had there been an open grave in Père Lachaise the two of them would have happily deposited the two of us therein despite probably having missed 30 percent of our punning banter.)

With that business done, let’s move on to our first stop at the rue de Lions – so named because it led to the menagerie of Charles V who had lions carved on its doors. The antiquity of the street is quickly evidenced because the street name appears not merely on a metal sign but is carved into the building itself. (Charles V {reign 1364-1380} had several noteworthy accomplishments during his reign. Here are a few:

- He built a new wall to secure a Paris that was considerably larger than that of Philippe II.

- He oversaw the expansion of the Château du Louvre which eventually gave way to the Palais du Louvre and ultimately the famous museum.

- He built the Bastille prison that was stormed on 14 July 1789.

- And, because his grandfather Philippe VI gave him the province of DauphinĂ© to rule until his coronation, he brought the term ‘dauphin’ into French.)

We then walked around the corner to the HĂ´tel de Sens. Although it was rebuilt in the middle of the 19th century, the turreted and fortified building is generally considered to be one of the area’s two remaining “medieval” townhouses.

The archdiocese of Paris was established in 1622. Until that year, diocesan authority rested with the archbishop of Sens some 120 kilometers southeast of Paris. The HĂ´tel de Sens was built to serve as the residence for the archbishops when they were in Paris. The current building was constructed in the late 15th century and, on close observation one can spot a cannonball that lodged in the wall on 28 July 1830. (The first hĂ´tel was built on the site in 1345 and was appropriated for use by Charles V as part of his royal residence known as the HĂ´tel Saint-Pol which was just outside the medieval walled city and which he preferred for its calmer, cleaner environment. {I’ve put a map of its approximate size and location in the photos folder linked above.} The city of Paris acquired the building in 1930 and after completing its restoration established the Bibliothèque Fourney – {Fourney Art Library} there in 1961.)Â

After crossing the bridge onto Île Saint-Louis where David showed us the oldest building on the island and took us on a brief stroll down the Quai de Bourbon, we circled back across the Pont Louis-Philippe and walked to and past the Holocaust Memorial and Museum. We thought of going in but demurred in the interest of time. (Merely passing through the layers of security would have caused a measurable delay.)

You can eat a Pletzel but not the Pletzl.

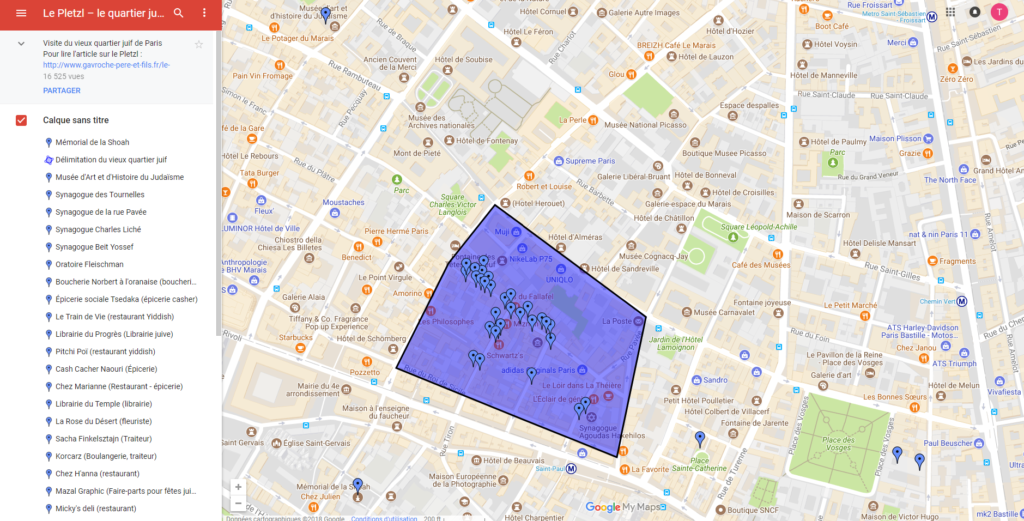

In the early 21st century, the Parisian district called le Marais is known for its gentrification, its trendy shopping, fashionable nightclubs and restaurants, being a center for gay Paris, and as the home of the Jewish Quarter or, as it’s known to its Jews, the Pletzl. Pletzl is a Yiddish word meaning little place. The name was an apt description for the Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution who settled within the larger Jewish Quarter in an area bounded by the rue du Roi du Sicile on the south, rues des Rosiers on the north, rue des Écouffes on the west and the Rue Ferdinand Duval (called rue de Juifs until about 1900) on the east. (A pletzel, by the way, is a Jewish flatbread similar to focaccia. It’s hard to find them for sale anywhere but if you’d like to try one, here’s a recipe for tzibele {onion} pletzel from Epicurious.) This (in purple) is the Pletzl today:

[Map from Gavroche Pere et fils.]

Although there’s evidence for a Jewish presence in France at least as early as the first century, the first clear confirmation of a Jewish community in Paris comes from the report of a murder in 583. This crime was reported more or less contemporaneously by the historian Gregory, Bishop of Tours (538-594) in his History of the Franks. Both the victim and the assailant were reported to be Jewish. Gregory reported that the victim, Priscus, who was a moneylender to the Merovingian king Chilperic 1, was on his way to a synagogue on the ĂŽle de la CitĂ©. Christians later demolished the synagogue and erected a church on the site.

The situation for the Jews of Paris was quiet and stable until the ascension to the crown of the wall-building Philippe Auguste. Four months after taking the throne, Philippe took the first of several actions designed to enrich himself at the hands of his Jewish subjects when he imprisoned all the Jews and demanded a ransom for their release.

Later in 1181, he annulled all loans made by Jews to Christians and took a percentage for himself as a fee for doing so. In 1182, he confiscated all Jewish property and expelled the Jews from Paris. He relented in 1198 readmitting the Jews but only after collecting yet another ransom and setting up a taxation scheme for his own benefit.

Expulsions and readmissions occurred periodically over the next two centuries culminating in 1394 with the expulsion ordered by another King we’ve encountered previously in this narrative, Charles VI. Although a small number found ways to remain, Jews would not be able to live legally in France until the reign of Charles IX in the middle of the 16th-century.

It wasn’t until the first third of the 18th century that Jews began resettling Paris in earnest. The Sephardic Jews (mainly of Mediterranean descent) who were generally wealthier settled in the Saint-Germain area on the Left Bank while the northern European Ashkenazim established their community in le Marais on the Rive Droite.

Both communities remained relatively small. It’s estimated that only about 500 of France’s 40,000 Jews were living in Paris at the time of the French Revolution. The earliest record of a synagogue in le Marais dates from 1788 and the oldest of the so-called “great synagogues” of Paris, the Synagogue de Nazareth, dates from 1852 but its location is farther north than our travels took us.

Today,

the area is more commercial than residential. About 65 percent of France’s 600,000 Jews live in Paris but they are spread throughout the city. The more affluent Jews live in the 17th while working class Jews generally live in the 19th and 20th though they can be increasingly found in the 11th and 12th according to a 2015 story on Haaretz.com.