Under a cloak of great secrecy, the Allied powers had begun planning their assault on northern Europe as early as 1942. Still, by the fall of 1943 even the most obtuse German military leaders surely knew that a major attack was imminent. Even so, it wasn’t until November 1943 that Hitler made the decision that the Reich could no longer treat the defense of northwestern Europe as a theater served by the lowest-grade Wehrmacht formations and where battered units from the Eastern Front could be sent to rest and refit before returning to the east.

On 3 November 1943, Hitler issued Directive 51. It begins:

For the last two and one-half years the bitter and costly struggle against Bolshevism has made the utmost demands upon the bulk of our military resources and energies. This commitment was in keeping with the seriousness of the danger, and the over-all [sic] situation. The situation has since changed. The threat from the East remains, but an even greater danger looms in the West: the Anglo-American landing! In the East, the vastness of the space will, as a last resort, permit a loss of territory even on a major scale, without suffering a mortal blow to Germany’s chance for survival.

Not so in the West! If the enemy here succeeds in penetrating our defenses on a wide front, consequences of staggering proportions will follow within a short time. All signs point to an offensive against the Western Front of Europe no later than spring, and perhaps earlier.

For that reason, I can no longer justify the further weakening of the West in favor of other theaters of war. I have therefore decided to strengthen the defenses in the West, particularly at places from which we shall launch our long-range war against England. For those are the very points at which the enemy must and will attack; there–unless all indications are misleading–will be fought the decisive invasion battle.

Holding attacks and diversions on other fronts are to be expected. Not even the possibility of a large-scale offensive against Denmark may be excluded. It would pose greater nautical problems and could be less effectively supported from the air, but would nevertheless produce the greatest political and strategic impact if it were to succeed.

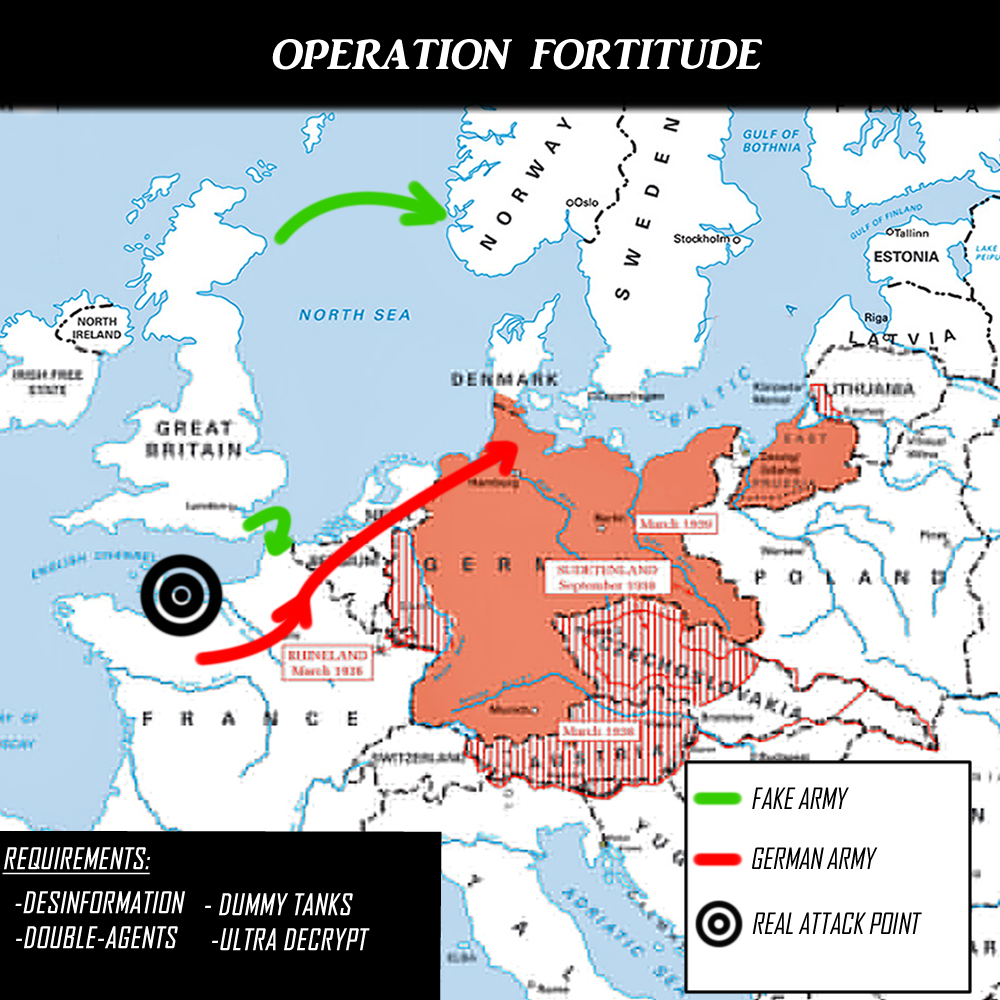

The last paragraph above demonstrates that one aspect of the Allies plans was embedded in Hitler’s mind – the one known as Operation Fortitude.

[Map from Stephen Ambrose History Tours.]

The main goal of Operation Fortitude was to convince the Germans that the main assault of the Anglo-American forces would occur in places other than those along the beaches of Operation Overlord as the D-Day attack was known.

At the end of November, Hitler sent Rommel to Denmark where the Field Marshal began an inspection of “Fortress Europe” the German defense line that stretched from Denmark in the north to the Bay of Biscay in the south. Until he made his actual inspection, Rommel’s only knowledge of Germany’s coastal defenses had come from the vivid imagination of Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels.

What he found was that Goebbels’ self-proclaimed impenetrable fortress was closer to the back lot of a Hollywood film studio or, had he suspected, to the false armored divisions the British and Americans seemed to be pointing at Calais, where the Germans had constructed some fortifications, (Fortitude South), and Norway (Fortitude North).

(Operation Fortitude was, perhaps, the greatest and most successful deception of the war. Not only did it divert German attention away from the planned landing sites in Normandy before the D-Day attack but continued long enough after the initial assault to convince the Axis that it was the Normandy landings that were the diversion.

Fortitude South, threatening a possible attack on Calais – the shortest crossing between England and France – relied more on the physical illusion of fake tanks, aircraft and dummy landing craft, and the fictional First U S Army Group.

On the opposite side of the island of Great Britain, North Fortitude was based in Edinburgh to simulate an invasion of Norway. Because the Allies believed that German reconnaissance aircraft were less likely to reach Scotland, the northern operation relied more on so called “Special Means” such as the controlled leaks through diplomatic channels and the use of German double agents as well as fake radio traffic. {Ben Macintyre’s book Double Cross is a fascinating exploration of the recruitment and use of German spies.})

[Photo from 3945km.com].

Seeing the state of disarray of the coastal defenses, Rommel spent the ensuing months pushing everyone within his area of responsibility to build field fortifications and bunkers, lay barbed wire, dig trenches, and emplace beach obstacles between the low and high tide limits. Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans fell far short of one of Rommel’s goals which was to have 12 to 15 million mines in place before the Allies landed – wherever that might be.

As he had in North Africa, the field marshal once again proved to be a formidable foe. Even though he came late to the plans to defend Northern Europe, his placement of mined beach obstacles (Hemmbalken) between high and low tide alarmed Allied planners to the degree that they changed the timing of the landings from high to low tide. This considerably increased the vulnerability of those making the initial landing – especially on Omaha Beach.

In an effort to deal with any airborne threat, Rommel ordered telephone poles and concrete posts – nicknamed ‘Rommel asparagus’ – planted throughout the fields and meadows of the areas immediately behind the most obvious landing points.

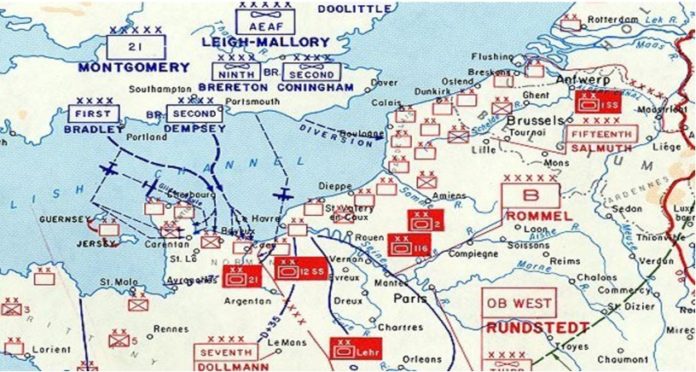

During this time, Rommel took command of Army Group B. When he initially took command, the group was based in Fontainebleau 70 kilometers south of Paris. Given that their responsibility would be the defense of Europe from Belgium to Brittany, Rommel relocated their headquarters closer to the front settling in La Roche-Guyon.

[Map from History Collection].

Many of Rommel’s warnings about the assault such as the superiority of Allied air power and the difficulty of moving German forces to Normandy went unheeded and proved true. (For example, due in large part to the efforts of the French Resistance, it took two weeks rather than two days for the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich to arrive in Normandy from the Limoges area of southern France.)

Overall, Rommel likely found the defense of Normandy immensely frustrating since it offered little chance for maneuvers and was under the constant attacks of Allied fighter-bombers both before and after D-Day. But as the operational commander on the scene, he dealt with the situation as it existed, not as he would have wished it to be. Allied advances continued and by late June, Rommel and nearly all the senior commanders knew that their situation had become untenable.

On 29 June, Rommel met Hitler for the last time at Berchtesgaden. Hoping to make the FĂĽhrer see reality, he suggested that perhaps political solutions should be considered. As was to be expected, Hitler would countenance no discussion on such matters.

The Field Marshal was traveling hundreds of kilometers each day meeting with his battle commanders, doing what he could, in a war that he knew was lost. On 17 July, soon after he left the Command Post of the 1st SS Panzer Corps to return to La Roche-Guyon, two Canadian Spitfires came diving down in a curving attack from behind and to the left.

Rommel’s driver was seriously wounded, lost control of the speeding car and crashed into a ditch. Field Marshal Rommel was thrown against the windshield post, sustaining serious head injuries. His career was over and his life would soon end in suicide.