Caillebotte, but didn’t sell.

By now you’re probably wondering what all of this has to do with Gustave Caillebotte and the seven artists I listed at the beginning of this series of posts. And you might have looked at his painting and thought, “It looks like an interesting painting but it doesn’t look particularly Impressionistic.” I’ll get to both.

Caillebotte was born in 1848 to an upper-class family. His father, Martial, had inherited the family’s military textile business and had also served as a judge at the Seine department’s Tribunal de Commerce. Sometime around 1860, Martial Caillebotte bought a large property in the small town of Yerres about 18 kilometers south of Paris where the family often spent their summers. It’s thought that it was here that young Gustave began to develop his interest in drawing and painting.

He earned a law degree in 1868 and a license to practice in 1870 but that practice was deferred when he was drafted into the army to serve in the Franco-Prussian war. The war ended in 1871 and, having already suspended the notion of practicing law, Gustave began studying painting with Léon Bonnat sometime shortly after his service ended. He eventually gained admission to the École des Beaux-Arts in 1873.

It was during this time that he met and became friends with Degas and through him several of the other independents and he appears to have spent more time with them than he did in the school. Though he was rapidly developing an accomplished style, he attended but elected not to participate in that first 1874 show of the Société Anonyme.

Martial died later that year and Gustave, as the eldest of three sons, inherited most of his father’s estate. This, together with his inheritance from his mother who died four years later in 1878, left him able to paint without needing to sell his work. It’s likely that this was among the factors limiting the appreciation of his talent until long after his death.

Though the painting of The Floor Scrapers shows his rapidly evolving skill, it was rejected by the 1875 Salon because they deemed its depiction of working class laborers vulgar. Together with seven other of his works it had it’s first showing in 1876 at the second Impressionist exhibition.

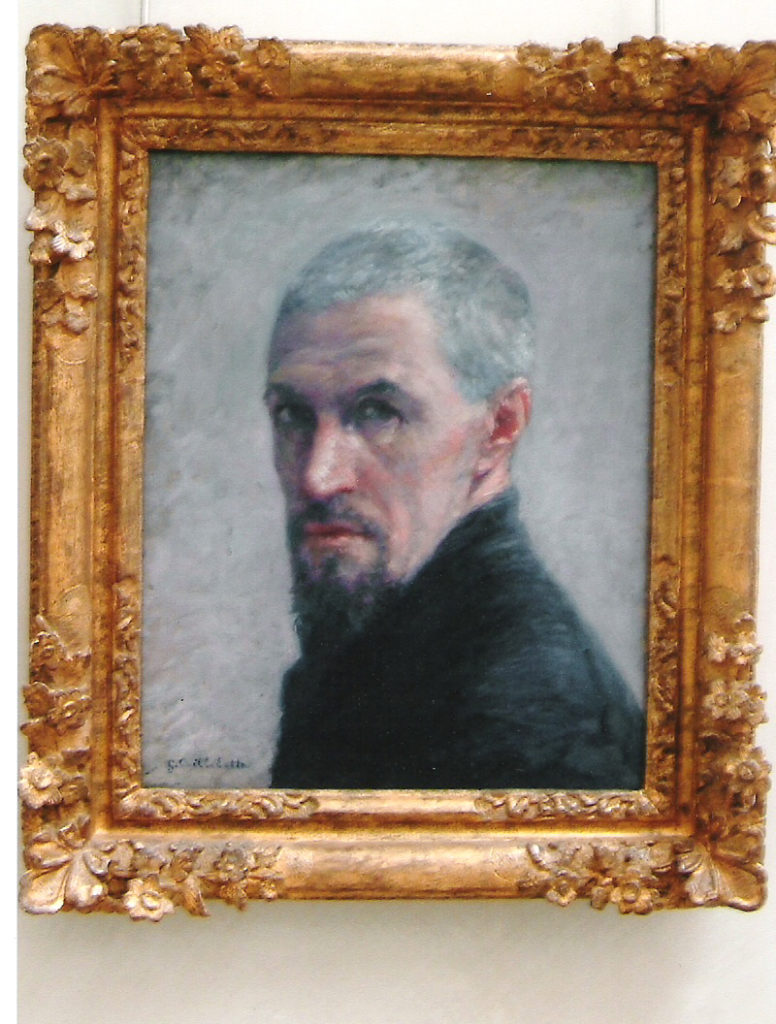

Caillebotte acquired a property at Petit-Gennevilliers, on the banks of the Seine near Argenteuil in 1881 and moved there permanently in 1888. His friend August Renoir was a regular visitor. Although he stopped exhibiting sometime around 1882, as this self-portrait painted in 1892 shows,

he not only continued painting for most of the remainder of his relatively short life, but he was stylistically flexible. (He died from a pulmonary edema at age 45.)

As he settled into his life at Petit-Gennevilliers, Caillebotte became known as a collector and supporter of the arts. He funded Impressionist exhibitions and supported his fellow artists and friends (notably Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro) by purchasing their works and, at least in the case of Monet, paying the rent for his studio.

Prepared for an early death, Caillebotte wrote a will that left his art to the French state with the instruction that they hang as a collection in the Musée du Luxembourg – the museum displaying works of living artists whose work would be displayed in the Louvre 10 years after their deaths.

His bequest, initially rejected by the French government, is known to have included at least 18 paintings by Pissarro, 16 Monet canvasses, nine by Sisley, eight each by Renoir and Degas, five by Cézanne and four by Manet. In fact, reaction to his “presumptuous” request was swift and rather vicious. Several professors at the École des Beaux-Arts threatened to resign if the government accepted the bequest. One prominent academic, Jean-Léon Gérôme wrote, “For the government to accept such filth, there would have to be a great moral slackening.”

However, Renoir, whom Caillebotte had named as his executor, was persistent in trying to persuade the government to accept the donation. Combined with the efforts of Caillebotte’s family, they eventually succeeded in having the government accept about half of the original collection including Manet’s The Balcony.

[Downloaded from the Google Art Project.]

The art was hung in a new wing of the Luxembourg museum in 1897 and the public attended in droves. As Derek Thompson notes in his book, The Hit Makers, it brought “unprecedented attention and even a bit of respect” to Caillebotte’s friends. Thompson goes on to write,

One century after the exhibition of the Caillebotte collection, James Cutting, a psychologist at Cornell University, counted more than fifteen thousand instances of impressionist paintings to appear in hundreds of books in the university library. He concluded “unequivocally” that there were seven (“and only seven”) core impressionist painters, whose names and works appeared far more often than their peers. This core consisted of Monet, Reboir, Degas, Cézanne, Manet, Pissarro, and Sisley. Without a doubt, this was the impressionist canon.

What set these seven painters apart? They didn’t share a common style. They did not receive unique praise from contemporary critics, nor did they suffer equal censure. There is no record that this group socialized exclusively, collected each other’s works exclusively, or exhibited exclusively. In fact, there would seem to be only one exclusive quality the most famous impressionists shared,

The core seven impressionist painters were the only seven impressionists in Gustave Caillebotte’s bequest.

His bequest so influentially shaped the impressionist canon that

Art historians focused on the Caillebotte Seven, which bestowed prestige on their works, to the exclusion of others. The paintings of the Caillebotte Seven hung more prominently in galleries, sold for greater sums of money to private collectors, were valued more by art connoisseurs, were printed in more art anthologies, and were dissected by more art history students who grew into the next generation’s art mavens eager to pass on the Caillebotte Seven’s inherited fame.

Interestingly, in the final gift to the French state, Renoir included two of Caillebotte’s paintings which were largely ignored by critics and art historians. It wasn’t until the second half of the 20th-century that Caillebotte’s talent received the recognition it deserved.