Filling a big space.

Throughout the 20th century, (and perhaps even dating back to NapolĂ©on) French presidents liked leaving their own architectural, urban planning, or cultural stamp on Paris as part of their legacies. For Georges Pompidou one signature he left on the city was replacing the old market at Les Halles with the Forum des Halles a large shopping mall that’s mostly underground. And, if you want to see architecture representing what the New York Times understandably called, “the worst of late twentieth century Modernity…”, Les Halles is the neighborhood to visit. Of course, if you want to see the largest museum for modern art in Europe, you also have to go to Les Halles and the Centre Georges Pompidou. (The Pompidou Center was originally the Beaubourg Centre and was posthumously named for the erstwhile French prime minister and president.)

[Photo from worldtoptop.com].

The history of modern art museums in Paris began when King Louis XVIII declared that the MusĂ©e du Luxembourg would house the works of living artists whose work was due to join the Louvre 10 years after their deaths. In the middle of the 20th century the works were split up and moved to three locations – the Palais de Tokyo, the Petit Palais, and the MusĂ©e du Jeu de Paume. Then in 1977, President ValĂ©ry Giscard d’Estaing oversaw the move of the modern art collection to the Pompidou Centre.

While all that art was moving about Paris, the plans were underway to transform the Gare d’Orsay into the MusĂ©e d’Orsay. The concept for the Orsay was that it would serve as a museum that bridged the gap between the classical art at the Louvre and the art now housed at the National Museum of Modern Art in the Pompidou Centre. The collection was drawn from the Louvre and the Jeu De Paume. The latter had housed most of the national collection of impressionist art since 1947. Generally, all the art in the Orsay would be from artists born after 1820 or who came to prominence in the Second Republic. President François Mitterand oversaw the museum’s opening in December 1986.

Once not an Impressionist, always an Impressionist.

An academic might describe Impressionism as the first distinctly modern movement in painting and, while the Impressionists didn’t set out with a notion of collectively naming their ideas, those ideas were both modern and unconventional. As is often the case, we can gain a better understanding by first looking at some history – in this instance looking back to the French Salon.

The French Salon had its beginnings in 1667 in the first royally sanctioned show under the auspices of the Académie de peinture et de sculpture (Academy of Painting and Sculpture). This school would eventually merge with the academies of music and architecture to form the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

It was, for most of the 18th and 19th centuries quite simply the most important art show in the world and also quite probably the most conventional.

The academics and judges who selected the artwork (which included sculpture but I’ll limit the current discussion to the paintings) had a rather rigid view of what was permissible in terms of both technique (precise, carefully applied brush strokes intended to hide the artist’s participation in creating the work thereby yielding a realistic almost idealized final product) and subject matter (religious, historical, or mythological themes were valued as was portraiture).

In the mid-1860s a group of four artists – Monet, Renoir, Sisley, and FrĂ©dĂ©ric Bazille who were studying at the AcadĂ©mie discovered that they had a common interest in painting landscapes and scenes of contemporary life. (Note that three of these four artists are on my list of seven and I suspect Bazille wouldn’t have made your list even if I’d asked you to name 10 Impressionist painters.)

While it wasn’t uncommon for the classical painters of the day to venture into the countryside to make sketches to serve as a basis for a scene to be realized and idealized in the artist’s studio, one of the ideas the Impressionists wanted to explore was capturing the momentary, sensory effect of a scene – the impression objects made on the eye in an instant. To accomplish this, when they moved from the studio to the streets and countryside, they produced completed paintings rather than mere sketches.

These painters loosened their brushwork and lightened their palettes using pure, intense colors. They eschewed the application of the golden varnish used in classical work to mute the colors while also abandoning traditional linear perspective and avoiding the clarity of form that had previously served to distinguish the more important elements of a picture from the lesser ones.

During this period, the Salon jury routinely rejected about half of the works submitted by Monet and his friends choosing instead works by artists faithful to the approved style. The Salon rejected this Manet painting in 1863.

Titled The Luncheon on the Grass, they were scandalized by his depiction of nudes in a contemporary setting. (They weren’t entirely prudish. Nudes were perfectly acceptable in historical, mythological, and allegorical paintings.) In addition to Manet’s work, the Salon rejected an unusually high number of paintings that year and it generated some measure of outcry especially from Manet’s supporters because he was so widely admired by these young artists.

As it happens, Emperor Napoleon III saw the rejected works of 1863 and decreed that the public be allowed to judge the work themselves. Thus was born the Salon des Refusés or Salon of the Refused. That year the Salon des Refusés attracted more viewers than the regular Salon. Perhaps sensing a threat, the Salon denied petitions requesting the set up of a new Salon des Refusés in 1867 and again in 1872.

Thus it was that in December 1873, that a group of these new school painters founded the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers). Their idea was that they would no longer apply to the Salon but would exhibit their artworks independently of it.

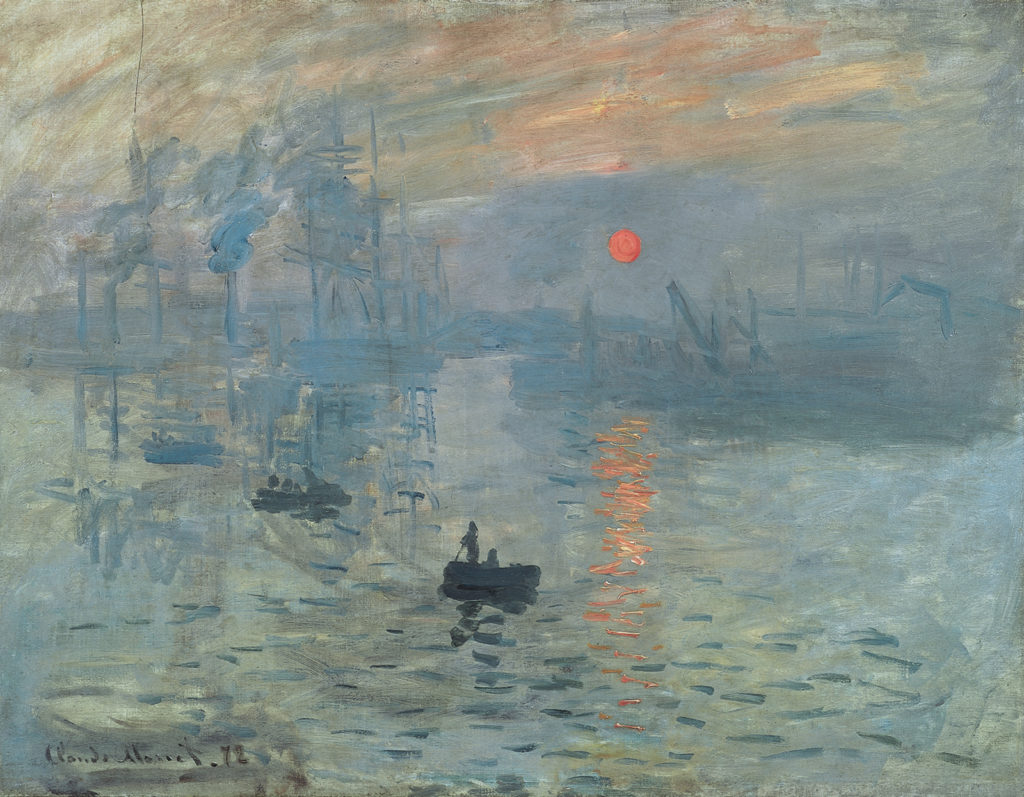

It was one painting at that initial exhibition and the comments of a lone satirical review that named the movement. This painting by Monet

titled Impression, soleil levant (Impression, sunrise) drew a particularly strong reaction from Louis Leroy in his review for the paper Le Charivari. He accused the group of painting nothing but impressions and wrote,

Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.

Rather than rejecting Leroy’s plaint, the artists, who might have previously referred to themselves as “independents” or “intransigents” saw impressionist as descriptive of their intention to accurately convey visual “impressions” and enthusiastically adopted it. Thus, although they espoused the principles of freedom of technique, a personal rather than a conventional approach to subject matter, and the truthful reproduction of nature and while each would ultimately pursue his or her own independent aesthetic, an artistic movement was born.

Next up, we’ll return to the role of Gustave Caillebotte.