Last stop before lunch – Notre Dame or more precisely

Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris.

So, why my insistence on precision? While it’s true that if I simply wrote Notre-Dame, the image that would come to the minds of most people (once my American friends banished associations with the university in South Bend, Indiana) would likely be one like this

of the famous Paris landmark. However, in France one can find 75 or so cathedrals with Notre-Dame as part of the name. Henceforth, I’ll use the shorthand version for this cathedral and will bestow the longer title on any other “Cathedrals of Our Lady” I encounter.

of the famous Paris landmark. However, in France one can find 75 or so cathedrals with Notre-Dame as part of the name. Henceforth, I’ll use the shorthand version for this cathedral and will bestow the longer title on any other “Cathedrals of Our Lady” I encounter.

Construction of Notre Dame began in 1163 during the reign of King Louis VII but wasn’t completed until 1345 under the reign of Phillippe VI – the first of the Valois monarchs. (Charles IV had died without a male heir and Phillipe, who was Charles’ first cousin, ascended to the throne on 1 April 1328. However, Charles’ closest male relative was, in fact, his nephew Edward III who was also the King of England. Although Edward initially accepted Phillippe’s claim, disputes between the two led to the start of the Hundred Years War which was, in turn, one of the factors complicating the completion of Notre-Dame.)

Notre-Dame was one of the first cathedrals built in the Gothic style and its construction took place across almost the entire Gothic period. While 182 years is exceptional, long construction periods for cathedrals weren’t uncommon in medieval Europe. In addition to the war, other factors came into play.

First and foremost was the matter of money. Building a cathedral wasn’t cheap and raising funds was solely the responsibility of the church. This alone presented ongoing challenges. In addition, only a limited number of qualified workers – all of whom had to be members of a guild such as the Masons – were available to work on any project at any given time. One might say, however, that the lengthy construction periods supported a town’s economic health because money paid to the workers would then flow back into other aspects of the local economy.

On the other hand, the length of time it took to build Notre-Dame also meant that various styles of architecture were incorporated into the design. Although it’s predominantly French Gothic, there are places where Renaissance and Naturalistic influences are apparent.

Perhaps Notre-Dame’s most famous exterior feature is its flying buttresses.

These arched exterior supports weren’t part of the original design. But after the construction of the cathedral began and the thinner walls popularized in the Gothic style grew ever higher, stress fractures began to appear. The cathedral’s architects, in an effort to fix the problem, built supports around the outside walls, and later additions to the building continued the pattern making it among the first buildings in the world to incorporate the flying buttress.

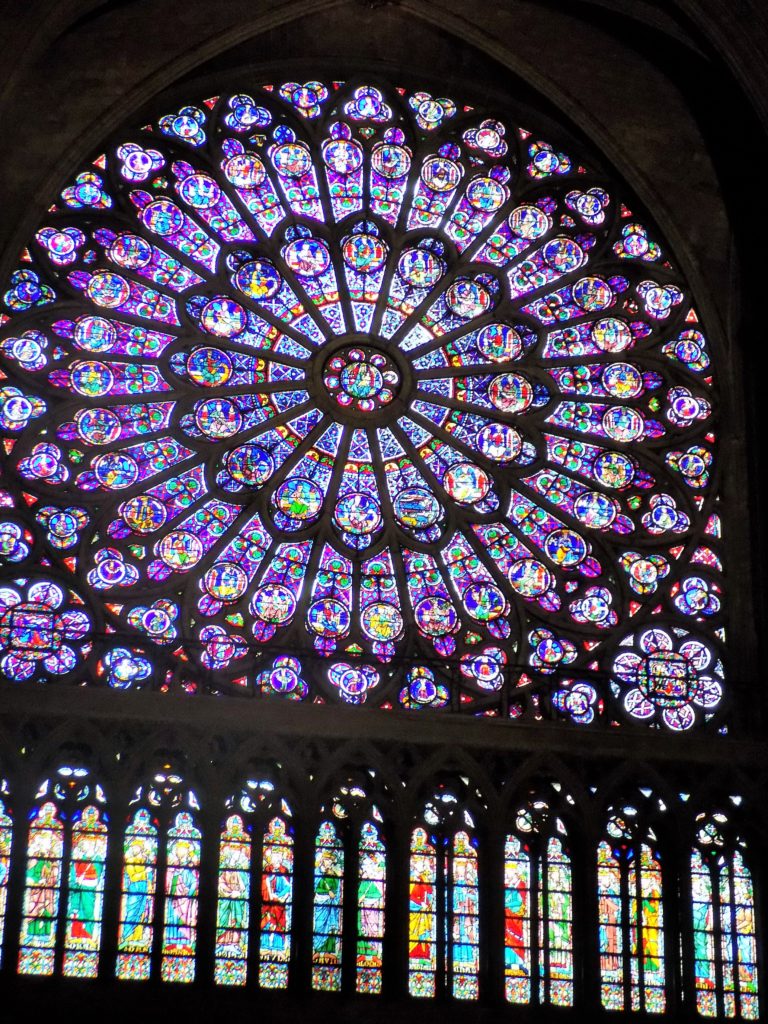

The buttresses allow the walls they support to have large sections cut out of them to permit the inclusion of expansive stained glass windows such as the famous Rose Window.

Whether you want to measure Notre Dame’s age from the laying of its cornerstone in 1163 – making it a bit more than 850 years old or from the date of its completion in 1345, this large and imposing cathedral hasn’t always been the icon it is today. In fact, it’s had a quite troubled history.

(Some facts about its size: Notre Dame is 130 meters long, 48 meters wide, and 35 meters high. The rose windows have a diameter of 10 meters. The cathedral’s pillars have a diameter of 5 meters and the twin towers go as high as 69 meters (387 steps). The south tower houses the 13 ton Emmanuel bell.)

The first real trouble happened in the 16th-century with the rise of the Huguenots – French Protestants who embraced the Reformed practices of Protestantism developed by John Calvin in Geneva rather than the teachings of Martin Luther. Like most in the budding Protestant movements, the Huguenots viewed Catholicism as corrupt and in need of being cleansed of its impurities. The Huguenots had a militant approach and they became known for attacking priests, monks, nuns, monasticism, images, and church buildings.

Among those buildings was Notre-Dame. Initially tolerant of the reform movement, King Francis the First adopted a more repressive approach after the Affair of the Placards in 1534. The movement continued to grow, however, and in 1548 a group of Huguenots looted Notre-Dame.

But the cathedral’s troubles didn’t end there. In the 18th century two forces conspired to reshape the church. First, the Gothic style had fallen out of favor and was even deemed by some to be barbaric. As a result, an effort began to modernize the church, beginning by removing much of the stained glass and replacing it with clear glass. The Gothic style choir screens were replaced by plain screens.

Of course, the second major force came in 1789 with the onset of the first French Revolution. The bell tower and spire from the 13th-century were removed and some of the bells were melted down and their metal re-purposed. In the Gallery of Kings the mobs decapitated 28 statues they thought were the kings of France but which were, in fact, representations of Biblical kings. A few of the heads survived and can be seen in the Cluny Museum but the sculptures seen by today’s visitors are re-creations.

Inflicting even more damage, the mob removed the lead roofing to melt the lead for bullets. Eventually, the church itself was made into a storage hall and stable.

The building fell into such a state of disrepair that it was slated for demolition. However, in 1804, Napoléon delayed the church’s destruction when he held his Imperial coronation there.

Two years before Napoléon’s coronation, a baby was born in Besançon who would play a pivotal role in the eventual restoration of Notre-Dame. In 1831 that baby, now a young man, published a novel whose three main characters were a poor bohemian girl, a deformed bell ringer, and a lecherous archdeacon. In French, the title was simply Notre-Dame de Paris. We know it in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Many people believe that the young Victor Hugo wrote the book to save the cathedral. If that was indeed his purpose, more than 13,000,000 visitors a year now share the fruits of his success.

2024 Update: Notre-Dame’s troubled history suffered another blow on 15 April 2019 a structural fire broke out in the roof space. The spire and two-thirds of the roof collapsed and the cathedral’s interior was also severely damaged.

By February 2023, workers completed the restoration of the stone arches and the oculus of the transept crossing. The breaches in the choir and nave vaults were sealed in May 2023. Work remains only on the transept crossing vaults meaning most of the cathedral’s vaults have completely regained their original form and structure.

You can see more photos from our tour here.

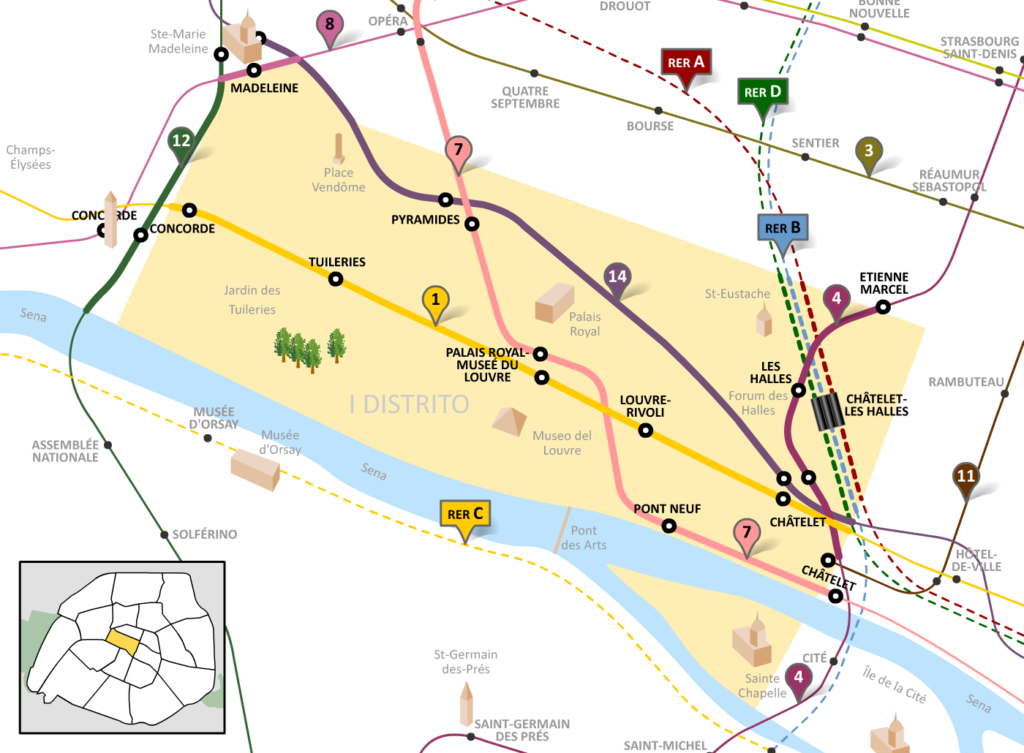

Because the afternoon’s planned activity required us be together as a single group, the tour’s organizers had reserved an entire restaurant – the Café-Restaurant Louis Philippe just a short walk back to the Rive Droite. If you look at a map of Paris and identify the sites I’ve described, you’ll see that we didn’t walk very far. While we came close to the first, the entirety of our walk was confined to the fourth. (My Paris experience was that people generally drop arrondissement when citing a location and I follow that convention here and henceforth.) Here are a pair of maps to help you out:

The shaded area on this map from the Paris Metro is the first. You can see that the western tip of Cité – including Sainte-Chapelle – is in the first but that Notre-Dame and the Hôtel de Ville are not. They are in the fourth.

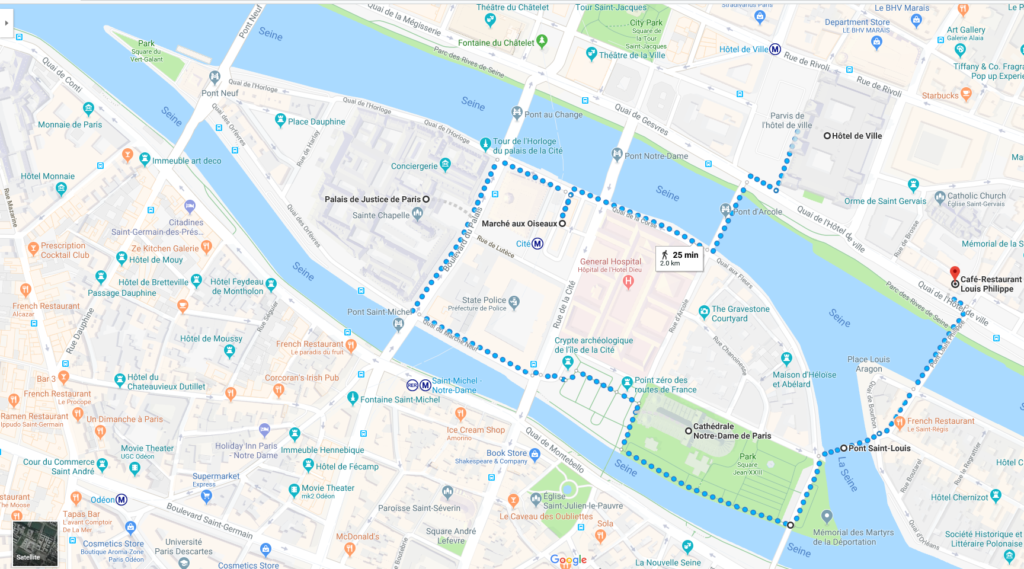

I’ve tried to approximate the course of our walk on the map below traced by the blue dotted path. It covered a total of about two kilometers.

(Please remember that you don’t have to suffer eye strain. You should be able to enlarge any photo with a single mouse click.)

Finally, a word about food. Since most of our meals will be either on the boat or in Paris, I will write very little about the food experience of the trip. To give you some idea about food in Paris, the website Yelp! lists reviews for nearly 28,000 places to eat and Trip Advisor lists more than 5,700 French restaurants alone.

While I can’t recall a bad meal, I also don’t remember any time when the food provided an exceptional, transporting experience. This is primarily because, even on our return to Paris, Patricia and I, knowing we’d get quality wherever we ate, usually sought geographic convenience when choosing a place to eat. However, I will say that the lunch at Café-Restaurant Louis Philippe was the most forgettable (a reaction later confirmed by David Downie and his spouse Alison Harris).

We’re only halfway through the first day, but the entry for the afternoon and evening will be quite entertaining. At least it was for Pat and me.