Missing History.

After what proved to be an unfortunately brief stop at Earthquake Lake, I resumed my journey toward Alder Gulch the home of two of Montana’s more famous “ghost towns.” (A location doesn’t need to be completely abandoned by all its human inhabitants to wear the description ghost town. If substantial elements of its past remain visible, a once populous place, be it a city, a town or even a neighborhood, can become a ghost town when it is still populated, as long as it has a population so much smaller than it had at its peak that the area is nearly unrecognizable. In many cases, ghost towns are created when towns that arose to support a single economic activity collapse when that activity ends or fails. However, natural disasters such as floods, sustained droughts, or human causes such as war or nuclear disasters can also create ghost towns.) Two such towns, created by the former process, Virginia City and Nevada City, exist side by side in Alder Gulch.

If you’ve been reading along since the outset – or at least since my tales of Deadwood – the reason for the rise of these towns should come as no surprise. On 26 May 1863, a half dozen men – Barney Hughes, Thomas Cover, Henry Rodgers, William Fairweather, Henry Edgar, and Bill Sweeney – found a spot to camp along a tributary of the Ruby River in what is now southeastern Montana. According to the legend, Fairweather and Edgar, hoping to find enough gold to buy tobacco for their party went to prospect a place of rimrock. Fairweather dug the dirt, filled a pan and told Edgar to wash the pan. That first pan turned up gold worth $2.40 and they immediately knew the gulch had great potential.

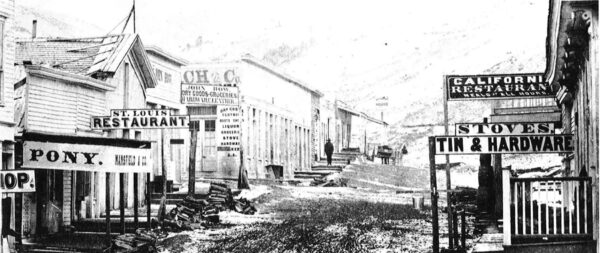

Their agreement to keep the discovery secret seems to have lasted about as long as it took them to smoke the tobacco they bought. Within weeks, miners, many of whom supported Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy, covered the hillsides of the gulch with tents, brush shelters, and crude log cabins and by 16 June, the Varina Town Company platted the town of Virginia City. Even with a city plan, the gulch itself became known as “Fourteen Mile City” for the numerous settlements that lined it.

[Photo from Virginia City website.]

In Virginia City, many of the miners wanted to name the town for Davis’ wife Varina – which they initially misspelled as Verona. There was a small complication, however. At the time, the area was part of the Idaho Territory and, as such, “belonged to the Union.” The newly elected miners’ court judge, Doctor G G Bissell, was a stubborn Unionist who submitted the name Virginia City instead.

From the outset, the camp was producing enough gold to win the Civil War for whomever controlled it. Due to this strategic importance, President Lincoln soon sent northern emigrants into the mining camp to help hold the town and, more importantly, the gold for the North. This, of course, caused all kinds of tension in the new city, and it quickly became one of the most lawless places in the American West.

By 1864, the population of Virginia City exceeded 10,000 and had perhaps as many as 1,200 buildings. (Today, it has a population of 132 and a mere 237 major structures.) Congress created the Idaho territory in 1863 with its capital in Lewiston which was more than 400 miles away. Neither the territorial legislature in Lewiston nor the rambunctious miners in Alder Gulch believed this was a reasonable arrangement.

The miners in particular began agitating for the creation of a new, more locally governed territory. Weather in the winter of 1863, delayed the arrival in Lewiston of the newly appointed Idaho chief judge, Sidney Edgerton, confining him in the mining town of Bannack just 80 miles west of Virginia City.

The miners loaded up a sympathetic Edgerton with $2,000 worth of gold and sent him back east to lobby Congress for the creation of a new territory which Montana became in 1864 when President Lincoln signed the Organic Act of the Territory of Montana. Because Alder Gulch housed nearly all of the new territory’s population, Virginia City became the territorial capital.

Over its lifetime, Alder Gulch has produced more than $100 million in placer gold with an estimated $30 million of that extracted in just the three years between 1863 and 1866. The total is the largest amount of placer gold in the Northwest. (Placer mining is the mining of stream bed deposits for minerals – most often precious metals – using open pit or surface excavating equipment.)

[Placer mining in Alder Gulch – photo from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

When gold was discovered in 1864 in Last Chance Gulch (in what today is Helena), miners began to move there from “Fourteen Mile City.” Even though miners continued finding gold in the area, by the early 1870s the exodus north reduced Virginia City’s population to only a few hundred. In 1875, the territorial capital was moved to Helena and Virginia City was on its way to becoming a ghost town.

So where, you might be wondering, is the missing history? My answer is that you need to read this section header not as a reference to my research about the area’s history being missing but to me missing the chance to see and experience that history in the two adjoining towns. When I arrived, both Virginia City and its nearby companion Nevada City, looked like this:.

Everything was closed. Nevada City essentially shuts down after Labor Day so I was two days late. When I was in Virginia City, the signs weren’t quite as clear and it looked as though some of its attractions might open at 11:00 but it was only 09:45 and with no other entertainment or activities – even a place to eat breakfast – apparently available, I wasn’t inclined to wait in the car for more than an hour. I was able to take a few other photos over the fence including this sign

which sent me on a research expedition when I got home. For me, the pithiest summary of the “most extraordinary trial in history” came from this site. It reads,

On December 19, 1863, Nevada City’s main street was the setting for the miners’ court trial of George Ives who brutally murdered a popular Dutch man named Nicholas Tibalt. The trial, which lasted three days and was attended by as many as 2,000 area residents, finally found that Ives had shot Tibalt before stealing his gold and several mules. After the miner’s jury found Ives guilty, proceedings immediately began to hang him. Within no time, a 40-foot pole was run through the window of an unfinished house nearby and a rope fastened to its end. Just 58 minutes after his conviction, Ives’ life ended on December 21, 1863. This first trial, conviction, and execution would become the catalyst for forming the infamous Montana Vigilantes. Within the next month, some 24 men found guilty by the vigilantes would also be hanged in the area.

Curiously, William F Sanders, Judge Edgerton’s nephew, was among the better known of those vigilantes.

I’d hoped to make one more stop on my way to Butte. Close to the nearby town of Whitehall there’s a pile of “lithophones” or ringing rocks. I’d read about it on Atlas Obscura but I’d forgotten a crucial bit of information they provide on their website, “A high-clearance vehicle is essential, as the last mile is on a steep, very irregular road.”

I stopped at a convenience store to grab a late breakfast snack and when I asked the woman working the cash register for directions, she looked out the window of the shop and said, “Honey, I hope you have a Jeep stashed close by because that little bug of a car won’t make it.” Mildly disappointed, I could only shrug and continue on my way to Butte.

Here’s a video of what I missed.