A journey’s end but not the end of the journey.

As they continued across Wyoming and into Idaho, Sacagawea, having demonstrated both her value and loyalty, repeated her role as an interpreter especially during council meetings between Indian chiefs and the Corps where Shoshone was spoken. As for the helpful presence of Pompey, Clark made a note in his journal on 19 October 1805, that the Indians were inclined to believe that the whites were friendly when they saw Sacagawea because no war party would travel with a woman – especially a woman with a baby.

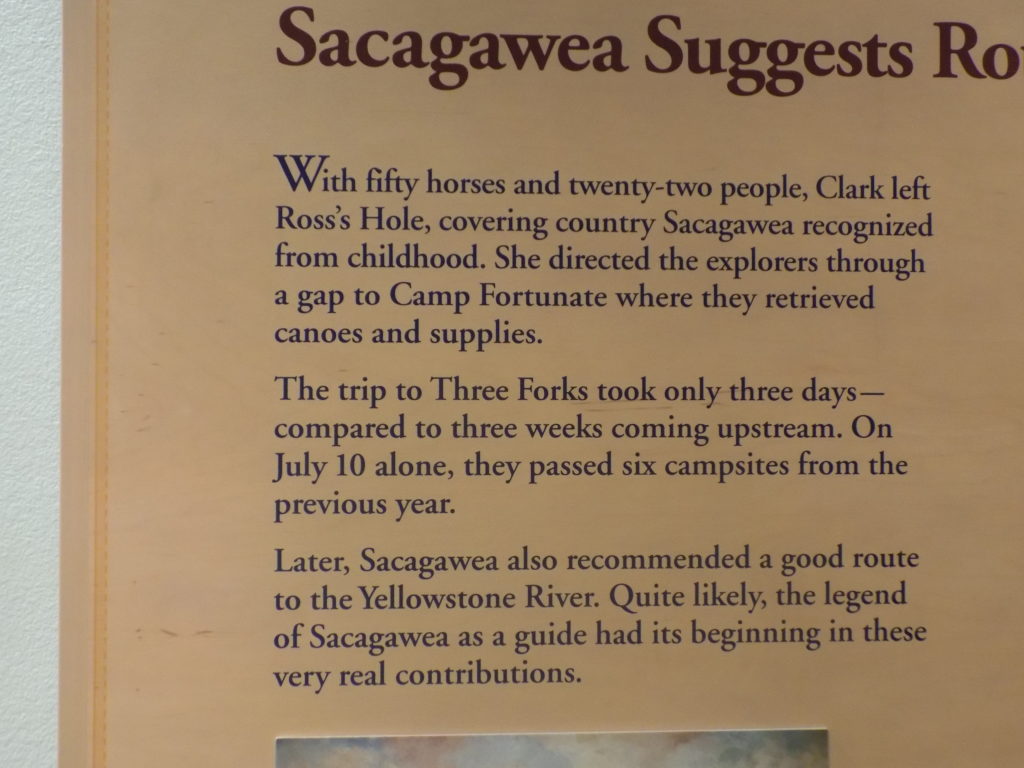

Although the information panel above refers to Sacagawea’s contributions on the return trip, nowhere is the degree of respect she earned on the outbound journey better displayed than with the expedition’s arrival near the mouth of the Columbia River on 24 November 1805. Knowing they would have to winter in place, the captains held a vote among all the members to decide where to settle until they could return to the east and Sacagawea’s vote counted equally among all the men. As a result of the election, the Corps stayed at a site near present-day Astoria, Oregon, in Fort Clatsop, that they constructed and inhabited during the winter of 1805-1806.

While at Fort Clatsop, local Indians told the expedition of a whale that had been stranded on a beach some miles to the south. Clark assembled a group of men to find the whale and possibly obtain some whale oil and blubber, that could be used to feed the Corps. Sacagawea had yet to see the ocean, and after willfully asking to accompany the men, Clark, who most sources indicate held her in higher esteem than did Lewis, acceded to her request.

On the return journey, Sacagawea and Charbonneau parted with Lewis and Clark at a Hidatsa village on the upper Missouri where Charbonneau received $500.33 and 320 acres of land. Sacagawea received nothing beyond Clark’s deep and abiding respect. From this point much of the historical record of the translators’ lives becomes subject to conjecture. It’s certain that some six years after the end of the expedition, Sacagawea gave birth to a second child, a daughter named Lisette. But details about Sacagawea’s life after Lisette’s birth become and remain a mystery.

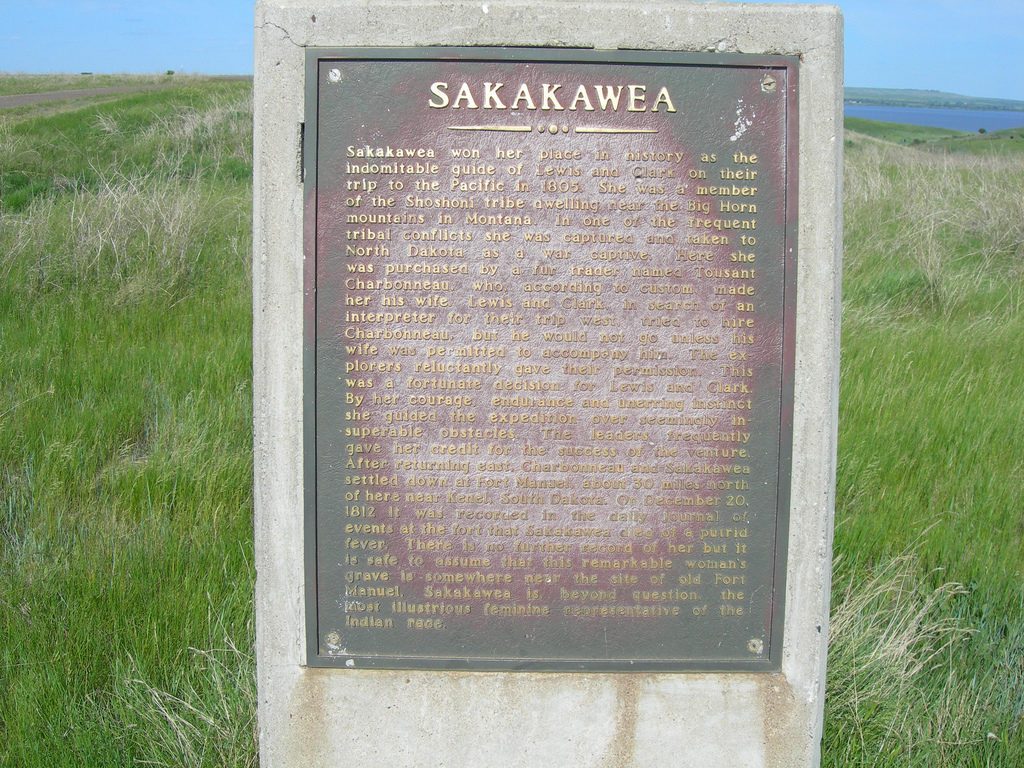

According to the journal of John C. Luttig, a clerk at the Fort Manuel Lisa trading post in present-day North Dakota, Sacagawea died there on the night of 20 December 1812. He wrote, “This evening the wife of Charbonneau, a Snake {Shoshone} squaw, died of a putrid fever. She was good and the best woman in the fort. Aged about 25 years. She left a fine infant girl.”

Although the exact site of the woman’s burial isn’t known, travel to the town of Mobridge, South Dakota near the Standing Rock Reservation and you can find this marker for Sacagawea:

[photo by Jimmy Emerson].

There’s additional evidence that the woman who died that night was, indeed, Sacagawea. First, in August 1813, William Clark legally adopted Sacagawea’s two children, Jean Baptiste and Lisette. Additionally, sometime between 1825 and 1828, Clark made a note in his cashbook of the whereabouts of his fellow expedition members. Next to “Secarjawea,” he wrote “Dead.” Given Clark’s adoption of her two children, the evidence seems clear cut.

Is there evidence to the contrary? Start by rereading Luttig’s entry and note that he doesn’t identify Sacagawea by name. Now, that alone isn’t enough to raise any doubt until we recall that Toussaint Charbonneau had two Indian wives. While Luttig’s description could certainly apply to Sacagawea, could he have written about Charbonneau’s second wife, also a Shoshone, called “Otter Woman” who’s said to have died before 1814?

There’s a geographical puzzle, too. Fort Manuel Lisa was sited near present day Pick City, North Dakota. Mobridge is some 170 miles to the south. It’s close to the Standing Rock Reservation but this is a Sioux tribal area and Sacagawea was Eastern Shoshone. One must wonder why someone would have taken the trouble to transport the body of a woman who died of “putrid fever” some 170 miles to bury her with people not her own.

Clark’s treatment of Sacagawea on the expedition indicates that he respected her and was quite fond of her son – the boy he called Pomp. Is it possible that Clark noted Sacagawea’s death to facilitate his adoption of her children? We know that Charbonneau and his family relocated close to Saint Louis in 1809 where he purchased land from Clark trying to become a farmer – a vocation for which the latter was ill-suited.

After just a few months, Charbonneau left Saint Louis to eventually join Manuel Lisa’s Fur Trading Company. During this time, he left his wife and son behind in Clark’s care. Both men seemed quite comfortable with this arrangement. Is it feasible that Clark agreed to adopt Jean Baptiste and allowed Sacagawea to return west and live the remainder of her life with her people? Or is this mere speculative fancy?

In April 1884, an elderly Shoshone woman named Porivo was buried on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming some 600 miles southwest of Mobridge. This is a photo of that grave.

According to the tribe’s oral tradition, Sacagawea had fled her French-Canadian husband and lived among the Comanche in Oklahoma in the 1840s before making her way to Wyoming in the 1860s and settling with her fellow Shoshone at the Wind River Indian Reservation the following decade.

Working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1925, Doctor Charles Eastman spoke with numerous Shoshone who had remembered the old woman and her stories about traveling with the Corps of Discovery. They also spoke of an elderly woman who adopted an Eastern Shoshone named Bazil. The name listed on the death certificate for the woman in the grave in the photo above is simply, “Bazil’s Mother.” Their testimony was enough to convince him to vouch for its validity and confirm Sacagawea’s identity.

But what of the name Porivo? Recall from the photo in the post A big rock, a bit of Spock that the name Sacagawea is from the Hidatsa words Sacaga (bird) and wea (woman). Is it conceivable that the old woman had adopted a new name? Perhaps she was simply using the name she’d had before her abduction. Speak to the Shoshone and they will tell you that the old woman who returned to Wind River would not have lied about her identity. It was not in her culture to do so.

These are the facts as I could find them. Believe the historians or believe the woman and the oral tradition (as well as some of my fill in the blanks speculation). The choice is yours.