Part one of the discussion of the treaties signed and broken ended with David Mitchell’s false assurances to the various tribes that there was no intent “to take any of your lands away…or to destroy your rights to hunt, or fish, or pass over the country, as heretofore.” It’s now time to explore that statement and probe some of its consequences.

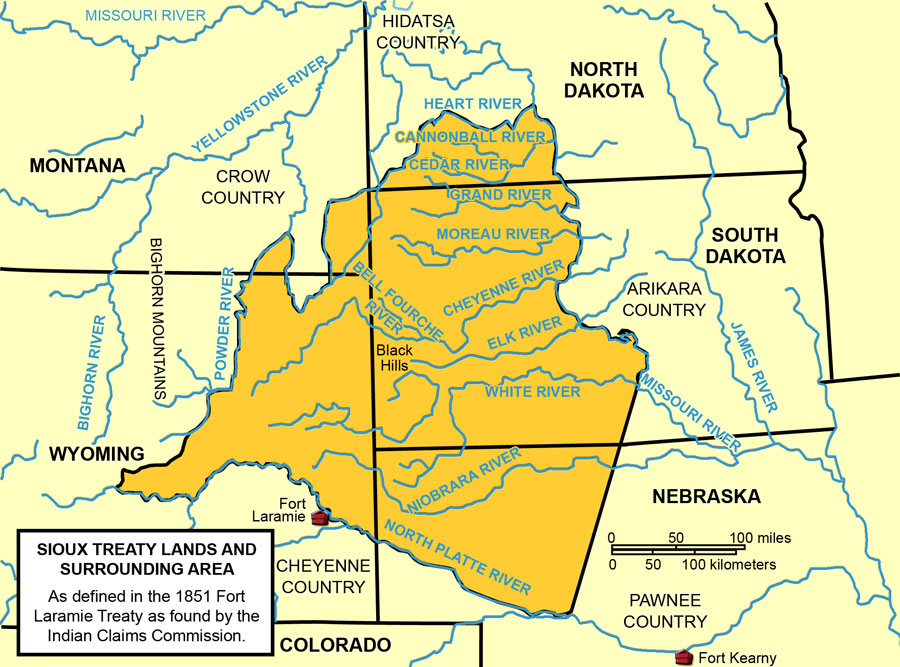

The map below highlights the lands granted the Sioux as well as some of the other tribes in attendance – though not all the tribes were pleased with this division of territory. Mitchell tasked De Smet and Bridger, both of whom the Indians trusted and who knew the region better than any other Europeans in attendance to create a map that respected traditional homelands.

(Though it’s not clearly defined on the map, the range of territory granted the Crow centered on the Bighorn Mountains. It spanned a large area covering more than 38.5 million acres from the Big Horn Basin on the west, to the Musselshell River on the north, and east to the Powder River; it included the Tongue River basin. While De Smet and Bridger might have recognized this as traditional Crow territory, bands of Cheyenne and Sioux had been encroaching on it for decades pushing the Crow into a shrinking pocket of territory. In fact, it was this ongoing history of skirmishes that led the Crow and Arikara to fight against the Sioux and Cheyenne in the Great Sioux War. Leading up to the battle at Greasy Grass, several Crow warriors would serve as scouts for Custer.

I’ll note at this point, that Little Bighorn is a translation from the Crow language. The Lakota Sioux called the river and the area where the battle was fought, Greasy Grass. I will use the terms interchangeably.)

[Map from ndstudies.gov].

In return for signing the Treaty, the Native Americans were to guarantee safe passage to settlers following the Oregon Trail and allow roads and forts to be built in their territories. They were promised payments of $50,000 to each tribe for past damages caused by the emigrants and an annual annuity of $50,000 for 50 years.

When it received the treaty, Congress unilaterally reduced the payment term from 50 years to 10. Then, increasing traffic over the Bozeman Trail led to increasing warfare between the tribes, the emigrants and the U S Army.

(The Bozeman Trail, established by John M Bozeman, was a diagonal shortcut for fortune seekers headed toward the gold fields at Virginia City, Montana. It left the Oregon Trail at Deer Creek Crossing near present day Glenrock, Wyoming. From there, travelers turned north through the Powder River Basin, which is bordered on the south by the North Platte, on the north by the Yellowstone River, on the west by the Bighorn Mountains and on the east by the Black Hills. Migrants then headed west toward the headwaters of the Tongue River, passing what are now the Wyoming communities of Bighorn and Dayton, thereby saving upward of 250 miles.

There was, however, a problem with Bozeman’s route. The trail crossed through prime buffalo-hunting grounds that had been promised to the Lakota Sioux under the terms of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Unsurprisingly, the Lakota, together with their allies the Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne, violently resisted this incursion onto their land. Predictably, a number of wars raged across the northern plains through the 1860s such as the Dakota and Colorado Wars in 1862 and the Powder River War in 1865.

By 1866, the trail became primarily a military transportation road. The tribes’ resistance to the presence of the forts and to military travel on the road became known as Red Cloud’s War, named for the Oglala Lakota Sioux war leader.)

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

It was Red Cloud’s War that brought the Sioux and American government together once again at Fort Laramie. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie expanded what became the Great Sioux Reservation to include a vast area of the land deemed Crow Territory in the 1851 treaty. It reduced the Crow territory from more than 38.5 million acres to about 8.5 million and left parts of Montana as unceded territory.

[Map of Sioux lands from ndstudies.gov].

The Great Sioux Reservation now had its boundaries on the North Platte River to the south and west, the Missouri River to the east and the Yellowstone River to the north and west. Thus, all of the western half of present day South Dakota, including the Black Hills was considered part of the Sioux Reservation. The terminology marks a key change, however, as what had once been Sioux territory was now a reservation. To help you grasp the difference, here is some language from the treaty itself:

the tribes who are parties to this agreement hereby stipulate that they will relinquish all right to occupy permanently the territory outside their reservations as herein defined, but yet reserve the right to hunt on any lands north of North Platte, and on the Republican Fork of the Smoky Hill river, so long as the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as to justify the chase. (From Article XI)

ARTICLE XV.

The Indians herein named agree that when the agency house and other buildings shall be constructed on the reservation named, they will regard said reservation their permanent home, and they will make no permanent settlement elsewhere; but they shall have the right, subject to the conditions and modifications of this treaty, to hunt, as stipulated in Article XI hereof.

ARTICLE XVI.

The United States hereby agrees and stipulates that the country north of the North Platte river and east of the summits of the Big Horn mountains shall be held and considered to be unceded Indian territory, and also stipulates and agrees that no white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the same; or without the consent of the Indians, first had and obtained, to pass through the same; and it is further agreed by the United States, that within ninety days after the conclusion of peace with all the bands of the Sioux nation, the military posts now established in the territory in this article named shall be abandoned, and that the road leading to them and by them to the settlements in the Territory of Montana shall be closed.

Many among the tribes thought they had won the war and that the treaty protected their sacred lands and traditional hunting grounds. In fact, at one point prior to signing the treaty, Red Cloud made a speech in which he said that he was ready for peace and that there was no need for more war. He stated that he wasn’t sure if he’d go to the reservation anytime soon, however, and he hoped the Oglala could visit and trade at Fort Laramie again, as they had in the more peaceful years of the past. His people had no desire to farm, and as long as there was game, he saw no need for them to learn.

The government’s objective was not merely to end the war but to settle the Indians down on the reservation, where they would become a more settled agrarian society, conform more to European ideas about land and land ownership, but, of equal importance, where they could be more easily controlled.