Open spaces, little known heroes and more rock faces – part 3

Go ahead. Make my day. Say the name Canyon de Chelly.

I’d guess that unless you’ve been in the area or actually visited this canyon, if you took my challenge, you got the canyon and de part right but mispronounced the rest. It rhymes with “make my day” and is pronounced “Canyon d’shay.”

Canyon de Chelly hadn’t been a part of my original plan but several people – including Linda, my host in Tucson, and the woman at the Powerhouse Museum in Kingman – had recommended it. It’s about 70 miles from Window Rock and barely a detour off the direct route to the Kayenta Inn and given that I only knew the time plus or minus an hour and didn’t know when the sun would set it seemed like it could be a worthwhile detour.

I’m going to take the answer to the obvious question about pronunciation from the Wikipedia page (with a spelling correction and the hyperlinks removed).

The name chelly (or Chelley) is a Spanish borrowing of the Navajo word Tséyiʼ, which means “canyon” (literally “inside the rock” < tsé “rock” + -yiʼ “inside of, within”). The Navajo pronunciation is [tséɣiʔ]. The Spanish pronunciation of de Chelly [deˈtʃeʎi] was adapted into English, apparently through modeling after a French-like spelling pronunciation, and now /dəˈʃeɪ/ də-SHAY.

By now, I hope you have a general idea of the processes involved in canyon creation – uplift and erosion – so I won’t detail the roles those forces played in the formation of Canyon de Chelly. This canyon sits at the northern end of the Defiance Plateau which has its southern terminus in the Painted Desert. Thus, it was the Defiance Uplift that set the stage for the carving of the canyon by several streams sourced in the Chuska mountains to the canyon’s east that feed the Rio de Chelly.

The Canyon De Chelly National Monument is entirely within the lands of the Navajo Nation and holds the distinction of being the only national monument that is jointly administered by a Native American tribe and the U S National Park Service. Additionally, there are several other unique facets of this national monument. But before I write about those, I want to share a picture I took at the end of my drive along the south rim. The formation is the twin sandstone spires – the taller of which rises 750 feet from the canyon floor – called Spider Rock. It is, understandably, the canyon’s iconic image

and is situated at one of the canyon’s deeper points. Another of Canyon de Chelly’s uncommon characteristics is that, in places, it’s only 30 feet from the rim to the canyon floor while its deepest spots are 1,000 feet from the rim.

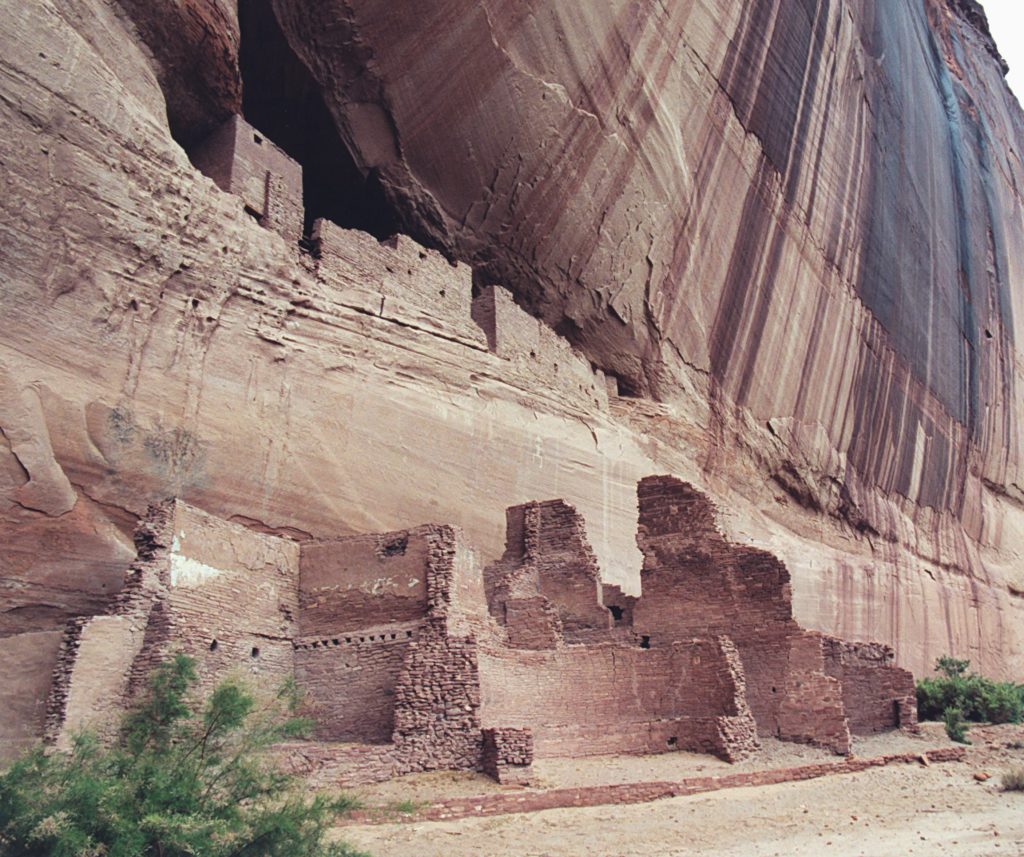

Sandstone predominates the canyon. The sheer walls are composed primarily of the De Chelly Formation dating to the Permian Age some 200 million years ago. Wind played a considerable role in shaping the canyon and many walls in the canyon are streaked with wind deposited shiny stains of manganese and iron oxides similar to the desert varnish seen in Petrified Forest. When you see a patina of stripes on the walls, it is usually comprised of carbonaceous plant material.

People of the canyon.

Unique among the sites we’ve encountered on this journey, is that people have continuously inhabited the labyrinth of canyons that comprise the national monument for almost 5,000 years making it the longest uninterrupted human habitat on the Colorado Plateau.

The first evidence of human habitation predates the Basketmaker culture by more than two millennia – dating back to approximately 2500 BCE. They likely lived in rock shelters at seasonal campsites hunting and gathering the canyon’s abundant fauna and flora.

With the arrival of the Basketmakers, came an age of agriculture. The principal crop, maize, had been introduced from the south and, with the additional cultivation of squash and beans on small farms tucked in corners of the canyon or carved on mesas, more permanent, if widely dispersed settlements arose.

The Basketmaker period lasted about 1,000 years until history notes another dramatic change – the aggregation of dispersed settlements into villages. This period, lasting from 750 to 1300, marks the time of the Ancestral Pueblo people. This era saw the domestication of turkeys and, with the addition of cotton as a crop, brought about new weaving techniques.

The White House Ruins, so named more for the shading of the wall than the structure itself, and accessible on the only hike into the canyon permitted without a local Diné guide, were probably among the earliest constructed by the Ancestral Puebloans.

The descendants of the Puebloans, the Hopi and the Navajo, continued living in the canyon until nearly all of them were driven out in a series of forced deportation marches, led by Colonel Kit Carson stretching from 1864-1866. Called the Long Walk of the Navajo, it is, in a way, the Dinè analog to the Trail of Tears. I won’t detail it but if you want to read or hear a bit about it, you can do so in this NPR story from 2005 or you can watch this video (with an emotional caution advisory).

After as many as four years of internment at Fort Sumner in New Mexico, the U S government finally allowed them to return to their ancestral home in the canyon.

End of the day.

Before reaching the end of today’s travel, I need to write a bit about the day’s final 70 miles to my stop for the night at Kayenta. I’m not sure why I jumped ahead of myself but when my phone’s Google Maps GPS indicated I’d be spending about three-fifths of the ride on Indian Route 59, I anticipated a dull hour buttressed in part by the difficulty of getting any radio signal through much of northern Arizona that wasn’t modern country music (which I can abide for short stretches but don’t particularly like) or evangelical Protestant (which I don’t like at all and can’t abide even for short stretches). Was I ever wrong about the ride.

It had been a long day and I was both tired and a bit hungry so I didn’t stop or even slow down to take many pictures but this road proved to be one of the most beautiful stretches of the trip. Cruising along with just the hum of the wheels and low-grade engine rumble to break the silence and rarely another car in sight, I was able to be quite present in the surrounding countryside – a long flat plateau framed by hills layered with varying hues.

Because the surrounding terrain was so flat, I could, as The Who sang, “see for miles and miles.” There was one rock formation that I believe I saw 20 miles before I ultimately passed it. I didn’t stop but slowed to take a photo when was closer to it.

If it looks different from anything I’ve shown you thus far, it is. On my way to Monument Valley tomorrow, I’ll pass a larger but similar formation which prompted some research so you must know by now an explanation is in the offing. Hang on.

I chose this hotel – the Kayenta Monument Valley Inn – because I believe (but never confirmed) that it’s independently owned and operated by Native Americans and because I was a bit misled by my lack of close attention to their website when I reserved the room and thought it closer to Monument Valley than it is. All the employees I met in my brief stay appeared to be indigenous tribal people.

My lack of energy and general disinterest in seeking anything better in a place as small as Kayenta, meant I’d have dinner in the hotel. The most memorable aspect of the night was the fact that of the five women working that night (a host and four servers / table bussers) four of them looked like they were more than six months pregnant. And with that, I’m off to bed.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026