At the end of the previous post, before my brief explanation of the Doppler effect, we left Vespo Slipher pondering the implications of his observations that the Sombrero nebula was moving away from the Milky Way while Andromeda was moving toward it. Over the next few years, Slipher measured two dozen more spiral nebulae and found they were all traveling at fantastic speeds. A few were moving toward the Milky Way but most of his observations showed redshifted spectra meaning they were moving away from our home galaxy.

This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image of the cluster Westerlund 2 and its surroundings has been released to celebrate Hubble’s 25th year in orbit and a quarter of a century of new discoveries, stunning images and outstanding science. The image’s central region, containing the star cluster, blends visible-light data taken by the Advanced Camera for Surveys and near-infrared exposures taken by the Wide Field Camera 3. The surrounding region is composed of visible-light observations taken by the Advanced Camera for Surveys.

Slipher presented his results of the speed of 15 galaxies to the American Astronomical Society in 1914, and, it’s said he received a standing ovation. Afterward, however, many astronomers – most of whom held to the notion of a static universe – didn’t know what to do with Slipher’s data. Why were these nebulae flying away at such amazing speeds? And, if they were, as his measurements suggested, outside our galaxy, what was their true nature and what was the distance to these objects? (Of course, Hubble’s work later provided answers to those questions and gave rise to the Big Bang Theory – no, not the long-running television show).

Thus, while many think that Edwin Hubble discovered the red shifting of galaxies and thereby the expansion of the universe, Vesto Slipher presented the evidence for this in a paper more than a decade before Hubble started working on it. While we know that a 25-year-old Hubble was teaching high school math in Indiana and wasn’t at Slipher’s presentation, he almost certainly would have been exposed to Slipher’s data while completing his PhD. We may never know the degree to which his work influenced Hubble but we do know that Slipher had a cautious nature and was not a self-promoter. Whether it was his humility or simply an abundance of caution that made him reluctant to gamble on interpreting his data as a discovery, he opted to keep quiet, continue the observational slog, and was ultimately outshone by a fellow astronomer.

(So pervasive is this elevation of Hubble’s work that in a TED Radio Hour first broadcast in 2013 but rebroadcast locally the day after I began drafting this entry, a scientist as distinguished as Brian Greene {among the best-known proponents of superstring theory} repeated it in a TED Talk. The first paragraph of the transcript below which I took from NPR’s website is host Guy Raz introducing a snippet of Greene’s talk. The emphasis is mine:

So sometime in the future, and we’re talking the far future, at some point there won’t be anything to see beyond our galaxy. Distant space will appear pitch black, empty, and to understand why, physicist Brian Greene in his TED Talk explained that you’ve got to go back to the year 1929…

BRIAN GREENE: … when the great astronomer Edwin Hubble realized that the distant galaxies were all rushing away from us, establishing that space itself is stretching – it’s expanding. Now, this was revolutionary, the prevailing wisdom was that on the largest of scales the universe was static, but even so, there was one thing that everyone was certain of – the expansion must be slowing down.

At least in the clip, even Greene neglected to mention Vespo Slipher.)

And then, there’s Georges LemaĂ®tre.

I have two reasons for bringing up Georges LemaĂ®tre. The first is that he, too, might have an indirect tie to Hubble’s work and the second is that he shines as a stellar example that, while I might believe that god and discovery cannot comfortably coexist, religion and science can. You see, LemaĂ®tre (full name Georges Henri Joseph Édouard LemaĂ®tre) was both a notable theoretical physicist and an ordained Catholic priest.

After being ordained in 1923, LemaĂ®tre became a graduate student in astronomy at the University of Cambridge where he studied with another famous physicist, Arthur Eddington – the first astronomer/physicist to confirm Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. Eddington introduced LemaĂ®tre to cosmology and to the fields of stellar astronomy and numerical analysis.

In 1927, LemaĂ®tre published a paper that gained him a measure of international fame. It was titled, “A homogeneous Universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae”. Although this work didn’t describe or introduce what we now call the Big Bang Theory, he did present a new idea of an expanding universe derived from General Relativity. It also included passages that pointed toward what became known as Hubble’s law, provided the first observational estimation of the Hubble constant and, after a struggle, managed to adhere to the idea of a finite sized unchanging universe.

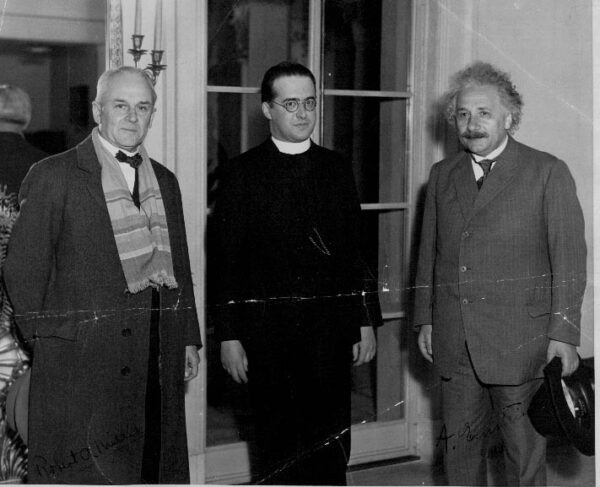

[Photo of Robert Millikan, Georges LemaĂ®tre, and Albert Einstein From Wikimedia – Public Domain.]

(It’s hard to blame him because at this time, even Einstein hewed to the prevailing belief in a static universe despite the fact that his theory of General Relativity all but required an expanding universe. So strong was Einstein’s belief that he posited something he called the cosmological constant. Hubble’s work eventually disproved the static universe and, by mid-20th century Einstein came to call the cosmological constant “the biggest blunder of my life”. Ironically, had he lived through the first decade of the 21st century he would have seen that very calculation become an essential part of cosmology perhaps thereby making his biggest blunder calling the cosmological constant his biggest blunder.)

To what degree was Hubble aware of LemaĂ®tre’s work? Again, we may never know. It’s plausible that he was unaware or knew very little about it. LemaĂ®tre’s paper was published in a little-known journal not widely read outside of Belgium. It wasn’t translated into English until 1931 and, for some unknown reason, the translation omitted the section pertaining to the estimation of the “Hubble Constant”. However, Eddington was quite aware of it and in 1930, he published a long commentary on LemaĂ®tre’s 1927 article, in which he described it as a “brilliant solution” to some of the outstanding problems of cosmology. But Hubble had announced his work in 1929 so we will never know how these threads wove together.

Through it all, Lemaître managed to keep his faith in spite of, or perhaps because of, the wonders of his cosmological discoveries. End of lesson.