Not as corny as Kansas in August.

Clyde Tombaugh was born in Illinois in 1906 but he grew up in Kansas where his family bought a farm when he was a toddler. Perhaps his unpolluted view of the night sky inspired his love of astronomy and, as a teen, he had dreams of attending college and having a career in that field. Unfortunately, a series of crop disasters ended his college aspirations. They did not, however, end his passion for the heavens.

He was so passionate that he built his first telescope, grinding the mirrors himself, at the age of 20. Unable to afford high quality commercial telescopes, in 1928 he cobbled together a 23-centimeter (9 inch) reflector out of the crankshaft of a 1910 Buick and parts from a cream separator. Not only was Clyde a sharp observer and an ingenious engineer, he was also a rather talented artist. Using this telescope, he made and drew observations of Jupiter and Mars. He sent those drawings to Vesto Slipher who had succeeded Percival Lowell as the observatory’s director after Lowell’s death in 1916. A rather unassuming man, Tombaugh simply hoped that Slipher or one of the other professional astronomers at Lowell would offer him some feedback about his drawings.

Rather than simply providing feedback, Slipher was so impressed with Tombaugh’s work that he offered him a job which Tombaugh excitedly accepted especially when Slipher’s offer remained open after Tombaugh revealed that he’d had no formal training. After about a year on site that Tombaugh spent on mostly menial chores, the professional astronomers at Lowell decided to task the new kid with the exceedingly tedious job of studying the images of the astrograph inside what is now called the Pluto Dome. (The device used in the search for Planet X was not an optical telescope but an astrograph which is typically used in wide field surveys of the night sky and is more efficient in detecting objects such as asteroids, meteors, comets and, as it turned out, missing planets than its observational cousin.)

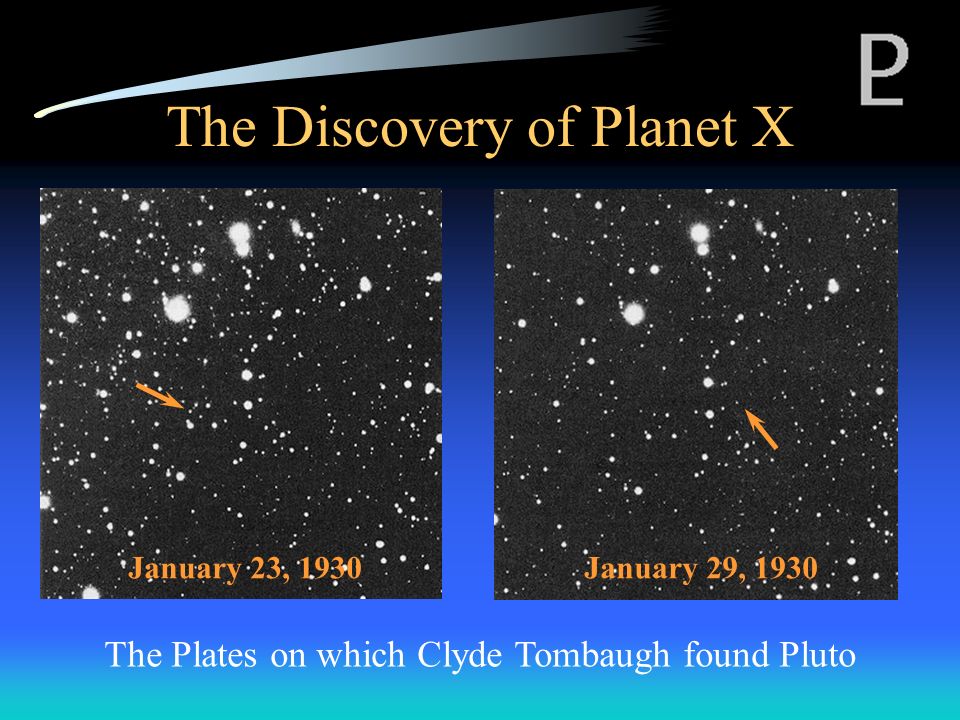

Tombaugh had to be both preternaturally patient and observant. Here, taken from the website slideplayer.com are the two plates he compared that led him to finding Pluto:

Of course, Tombaugh didn’t have the benefit of the arrows. He had to compare the position of every speck of light on one plate with every speck of light on the other and find the one that had unexpectedly changed position – thus my comment about his patience and observational skills. But Tombaugh was aided in his discovery by yet another coincidental set of circumstances.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the solar system’s plane of the ecliptic. If the term is unfamiliar, here’s how NASA’s website defines it:

The ecliptic plane is defined as the imaginary plane containing the Earth’s orbit around the sun. In the course of a year, the sun’s apparent path through the sky lies in this plane. The planetary bodies of our solar system all tend to lie near this plane, since they were formed from the sun’s spinning, flattened, proto-planetary disk.

Thus, this plane would be the logical place to look for an undiscovered planet. But there’s a problem with Pluto. It doesn’t lie near the plane of the ecliptic. All the other planets do and this means they’re always aligned. Keep this in mind the next time you hear the expression or a news story about planetary alignment.

(NASA adheres to Pluto’s recent classification as a dwarf planet. You see, Pluto’s orbit is inclined at a 17-degree angle away from the plane of the other eight planets. This is, perhaps one of the reasons Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet. Another arose simply from its size – {yes, size matters}. Seven planetary moons elsewhere in the solar system – Ganymede, Calisto, Io and Europa around Jupiter, Titan and Triton orbiting Saturn and Neptune respectively and Luna, our own local moon – are all larger than Pluto.)

Pluto’s orbit is also far more elliptical than the other planets and this contributes to the length of its orbital year – equivalent to 248 Earth years. Thus, Pluto crosses the ecliptic twice for each of its circuits of the sun or once every 124 years. It’s likely that if Tombaugh had been searching for Pluto in 1920 or 1940, it might have been orbiting along its merry way but well outside his survey area near the ecliptic plane and thus gone undiscovered for some unknown number of years.

I have a few more notes about Pluto before I move on to a brief discussion of one of the important contributions Vesto Slipher made to modern astronomy beyond hiring Clyde Tombaugh and approving his assignment to the task of searching for Planet X.

First, Pluto’s discovery created some chaos in the astronomical community. You see, as I noted above, Pluto is tiny. It’s so small that if you laid one edge of Pluto on top of Lowell Observatory and traveled across the entire planet, you’d still be nearly 450 miles short of reaching Washington, DC. Astronomers looked at Pluto and realized that it had nowhere near the mass to disrupt Uranus’ orbit to match the observations. And, of course, its weird orbit didn’t help the case either.

What they did in attempting to reconcile the problem was to assess much of the new data that had accumulated about Neptune since its discovery and were able to recalculate its mass. The new calculations, eventually confirmed by Voyager 2 in its close encounter with the ice giant, gave Neptune enough mass to affect the orbit of its fellow ice giant, Uranus, to match the observed data.

In regard to its name, continuing a long tradition of allowing the discoverer of a body to name it, the International Astronomy Union conferred that distinction on Lowell Observatory and they solicited public suggestions. It was Venetia Burney,

[Photo from Pluto Safari – Public Domain].

an 11-year-old English schoolgirl who suggested the name Pluto because it was dark and far away, like the god of the underworld. She told her grandfather, a librarian at Oxford’s Bodleian Library, who in turn passed on the suggestion to his friend Herbert Hall Turner who happened to be an astronomer. Hall then cabled the suggestion to the Lowell Observatory. Astronomers at the Lowell Observatory liked the suggestion, and Tombaugh’s newly discovered celestial body was officially named Pluto on 24 March 1930. Venetia received £5 as a reward for her suggestion.

Choosing the name Pluto created another happy confluence for the Lowell astronomers. If you look at the upper right corner of the slide of Tombaugh’s plates, you can see Pluto’s symbol:

It’s a barely stylized union of the letters P and L coincidentally, the initials of the man who started all this, Percival Lowell.

The last Pluto related item concerns Vesto Slipher who, in what I assume was a deliberate nod to history, published an “Observation Circular” announcing Pluto’s discovery on 13 March 1930 – 149 years to the day after Hershel’s discovery of Uranus.

In the next post, we’ll look at another major discovery that came from the Lowell Observatory and introduce you to Vesto Slipher – the observatory’s director at the time.