Let’s climb Mars Hill and discover Pluto!

Okay, so Clyde Tombaugh beat me to that on both accounts and, while I can’t tell you the exact date he first ascended Mars Hill to join the staff at Lowell Observatory, I can tell you that he discovered Pluto in what is now the Rotunda Museum on Tuesday, 18 February 1930 – at about 16:00 if our tour guide is to be believed. Still, I think the story of Tombaugh, Vesto Slipher, Percival Lowell, and the discovery of Pluto (but also other noteworthy events and discoveries in which Lowell Observatory has played an important part) is an interesting one and while it’s filled not with intrigue but coincidence it is a story worth retelling. I invite you to pass judgment on my impression.

It was a relatively short drive from Walnut Canyon back to Flagstaff where I’d spend the night. It was still too early to check in at my hotel so I had Google Maps take me directly to the observatory. It’s a surprisingly large campus with movies and exhibits in the visitor’s center, two regular tours (I’d go on both), and several open air astronomical walks.

I’m not going to write much about the observatory’s founder Percival Lowell beyond noting that he was the child of a well-to-do Massachusetts family who graduated from Harvard with honors and a degree in mathematics. Lowell fervently believed that the Martian “canals” (a secondary translation of the Italian ‘canali’ meaning channels that were first mapped by Giovanni Schiaparelli)Â were evidence of an advanced civilization on Earth’s nearest neighbor and proving this hypothesis provided his principal motivation for establishing his namesake observatory in 1894. Failing at that, Lowell turned his effort to finding the mysterious Planet X whose existence was predicted by perturbations in the orbit of Uranus. Lowell died in 1916 without, of course, having proven his Mars hypothesis or discovering Planet X. But someone at his observatory would fulfill that last dream.

This might seem hard to believe but the first coincidence at the trailhead of Clyde Tombaugh’s path to the discovery of Pluto dates to 1612. In this year Galileo Galilei observed Neptune when it happened to be very near Jupiter. Observing it on two successive nights, he noticed that it moved slightly with respect to another nearby star but, according to his notes, he thought it was just an unremarkable dim star. The night prior to his observation had been cloudy and when he was observing on subsequent nights the “dim star” was out of his field of view. Had he seen it on either set of nights, Neptune’s motion would have been obvious to him and he would have realized that the dim star was, indeed, a planet. Neptune is too dim to be seen with the naked eye and it would be more than 70 years until Newton published Principia, and nearly a century beyond that before William Hershel announced his observation of Uranus on 13 March 1781. So, for the 169 years between Galileo’s and Hershel’s observations, there was no reason to suspect that the solar system had more than the six known planets.

(The word planet, by the way, traces back to ancient Greece. The Greeks held a geocentric view of the universe but they noticed five bodies (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) that moved differently from all the others in the night sky. They called these bodies ‘asters planetai’ meaning “wandering stars.” Copernicus came along in 1543 and published his model of a heliocentric universe and by the time Galileo was making his observations, the concept of planetary motion was well-established – if not globally embraced.)

Rest your eyes for a moment on the exterior of the Pluto Dome. Now let’s continue our exploration of the solar system.

Because of all this confusion concerning Neptune’s status, and because, it too, is invisible to the naked eye, Uranus is considered the first discovered planet. Thus, when he announced his discovery of the seventh planet (with the third largest planetary radius and fourth largest planetary mass), Hershel and his telescope became the first to expand the boundaries of the solar system. In truth, Hershel thought he was observing a comet and it was the work of two other astronomers – Anders Johan Lexell, a Swede working in Russia, and Johann Elert Bode working in Berlin who independently calculated the generally circular nature of Uranus’ orbit settling the debate concerning its planetary status although Hershel didn’t acknowledge it until 1783.

(An aside on the planet’s name: Those of you who are familiar with Greek and Roman mythology, might notice that Uranus alone is named after a Greek deity. All of the others, including our dwarf planet friend Pluto, have namesakes that are Roman deities. But the story surrounding Uranus’ name is even odder than this exceptionalism.Â

During the original discussions following its discovery, Nevil Maskelyne, the Astronomer Royal, asked Herschel to give a name to “his” planet. In response to Maskelyne’s request, Herschel decided to name the object Georgium Sidus (George’s Star), or the “Georgian Planet” in honor of his new patron, King George III. {Yes, the same “mad” King George against whom the American colonies rebelled.} Thus, if Hershel had had his way, the planets would be Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, George, Neptune and, {if you insist} Pluto.

It was actually Bode who, in 1782, a year before Hershel even recognized “his” planet as a planet, suggested Uranus which was the Latinized version of the Greek god of the sky, Ouranos. I’m uncertain why he chose a Greek rather than a Roman God. As a last side note, the British held out until 1850 when the royal Nautical Almanac Office finally let go of George.)

Planets behaving badly.

Further observations of Uranus created a new problem. The planet appeared to be behaving badly. Its orbit didn’t fit with the predictions of the Newtonian models that otherwise worked so well. This led Alexis Bouvard to deduce that its orbit must be subject to gravitational perturbation by an unknown body – and a big one at that. At that point, a fellow named Urbain LeVerrier got to work crunching the numbers. His calculations, which predicted Neptune’s location to within a degree (an astonishing feat considering he had no computer to assist him), led Johann Galle to observe Neptune with his telescope on 23 September 1846 – making it the only planet in the solar system found by mathematical prediction. (At this time, the Brits were still calling Uranus George.) Â But there was still a problem. Neptune’s calculated mass wasn’t enough to create the observed perturbations in Uranus’ orbit. Thus, something else, we’ll call it Planet X for a mathematical unknown, had to be out there and Percival Lowell came to be among those who searched the skies seeking the missing Planet X.

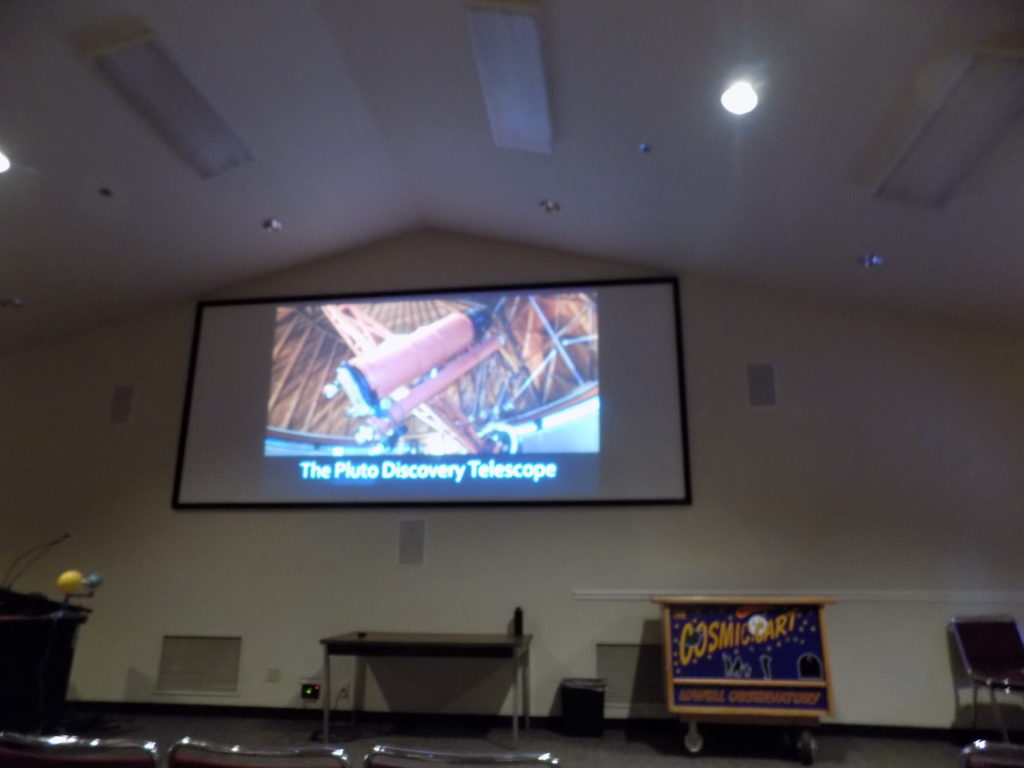

So, had Galileo not ben making his observations on some cloudy nights or had Neptune’s mass been calculated accurately from the outset, it’s likely the search for Pluto would have ceased. But a few cloudy nights and an error in math kept people looking for the object that was bothering Uranus. Before I get to yet another coincidence that aided in Pluto’s discovery, let me write a bit about the man who made the discovery, Clyde Tombaugh. (I should note that the Pluto Discovery Telescope is being restored so this photo is all I saw of it.)

Prepare to meet Clyde Tombaugh, the man who discovered Pluto, in the next post.