Terror follows pizza (and I don’t mean lactose intolerance).

I didn’t think our time at Shoes Along the Danube or in the October 1956 memorial under Kossuth Square had yet sufficiently atoned for yesterday’s phallic frivolity at the Market so the next spot on our agenda was the Terror Museum. I’d read that this was a place one should visit while in Budapest and, although I didn’t have a precise idea what to expect, I didn’t expect a place called the House of Terror to be barrels of fun. However, it was close to lunchtime when we finished our tour of Parliament so we decided finding food should be our first objective.

We left Kossuth Square and, map in hand, wandered along some side streets hoping to find our way to Ter├®z krt. (krt, I learned later is the abbreviation for boulevard) because it looked like a major thoroughfare and it intersected with Andr├Īssy Street at Oktogon, the large traffic circle just two blocks south of the House of Terror. Surprisingly, we passed no places to eat along that stretch of Ter├®z krt. but found plenty when we reached Oktogon including a Burger King and a TGI Friday’s.

We passed on those as well as the small place selling gyros before settling on another small restaurant that was, of all things, a pizza parlor. As I recall, they offered several unique toppings and Pat and I shared a thin crusted pie with minimal sauce that was tasty but not quite what we’d get in the States. I think I had a beer to go along with it because little could be better than beer and pizza in Budapest on a late August afternoon.

Not knowing exactly what to expect we made the short walk up┬ĀAndr├Īssy street to the House of Terror.

The museum presents details of life under both the extreme right-wing Nazi occupation and the extreme left-wing Communists. Its location at 60 Andr├Īssy is no accident. During the Nazi occupation, the building housed the secret police of the Arrow Cross and when the Soviets came to power, this was the headquarters of the dreaded ├üVH and its predecessor the ├ü V ├ō. As you walk toward the entrance, portraits of some of the victims line the exterior wall near eye level (or for me, just above eye level).

We had to wait a bit to get in because the crowd was overwhelming the museum’s capacity and this museum requires a long time. Once inside, among the first sights to greet you is a Soviet tank situated at the bottom of the Wall of Victims.

The exhibition begins on the second floor and, just as there’s nothing gentle about military occupation and systematic governmental oppression characterized by mass arrests, torture, and collective discrimination and resettlement, there is nothing gentle about the exhibits in the House of Terror.

You begin in the Hall of Double Occupation. (All of the descriptions are from the museum’s website.)

The room displays the two successive foreign occupations of Hungary. One part of the monitor-wall depicts the genocidal Nazi r├®gime: Hitler and the jubilant crowds, as well as the horrifying photographs of Bergen-Belsen, while on the other side we can see the Red Army, the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and military parades along Red Square. There are some shots of the Hungarian Army’s participation in the war against the Soviet Union, as well as of the siege of Budapest. The pictures on the walls of the hall portray the devastation caused by the war in Hungary. The four interconnected plasma monitors let us follow the transformation of Central Europe from the First World War to the end of World War II.

The next area is called the Passage of the Hungarian Nazis (Arrow Cross Party). The “House of Loyalty” was the description given this building by the Arrow Cross.

On the wall we can see Ferenc Sz├Īlasi’s “Report to the Nation”, which he published after the putsch of October 1944. Opposite is an Arrow Cross poster, and next to it a photo showing the exhumation of the victims of the Maros Street mass murder. (Armed units of the 12th district Arrow Cross organization massacred Jewish patients and staff of the Maros-street hospital.) A frieze of Arrow Cross insignia frames the walls of the corridor, similarly to the way they were used as decorations in the “House of Loyalty”.

Next, you pass through the Gulag.

The hall conjures up Soviet forced-labour and slave camps. Camp centres, where Hungarians languished, are specially marked on the carpet-map. The monitors show reminiscences, contemporary photographs, as well as pictures of the desolate, inhospitable Russian and Siberian countryside. The display cases contain relics, the original paraphernalia used by the detainees.

The monitors that the text references often have personal and harrowing stories and I couldn’t watch them all.

From the Gulag you

enter an Arrow Cross assembly hall. The ghostly figure of Ferenc Sz├Īlasi stands at the head of the table. Informative photos of the Arrow Cross movement can be seen on the back wall. The monitors show contemporary filmed material, amongst them the deportation of Hungarian Jewry, Arrow Cross propaganda clips, the forcible return of war criminals and a series of pictures documenting the interrogations carried out in this building. Under the monitors Arrow Cross and SS uniforms are displayed. Loudspeakers blare sound clips from the program of the Hungarist H├Łrad├│ (Hungarian Nazi Newsreel). Ice-floes drifting on the Danube projected onto the wall at the end of the hall conjure up the memory of Jewish victims shot on the Danube embankment in the winter of 1944-45.

The section called Changing Clothes

┬Āin which the central piece continually rotates, is a dramatic visual presentation showing not only one way by which people coped but also that the┬Āouter trappings┬Āof oppression can change┬Āwhile its effects, whether from the right or the left, do not.

┬Āin which the central piece continually rotates, is a dramatic visual presentation showing not only one way by which people coped but also that the┬Āouter trappings┬Āof oppression can change┬Āwhile its effects, whether from the right or the left, do not.

The Russians and their surrogates┬Āthen replaced the Germans and theirs. The Room of Soviet Advisors uses artifacts and documentaries to depict the Soviet presence as they attempted to force their own methods and lifestyle on to Hungarian society.

And the last stop on the second floor is Resistance. In a system that depended on terror and fear you learn here that resistance spread to every level of society. You also learn that many resisters were killed and buried in unmarked graves.

On the first floor you face the decades of collective persecution that followed the end of the Second World War. Beginning in the Room of Deportation and Resettlement then walking through this area

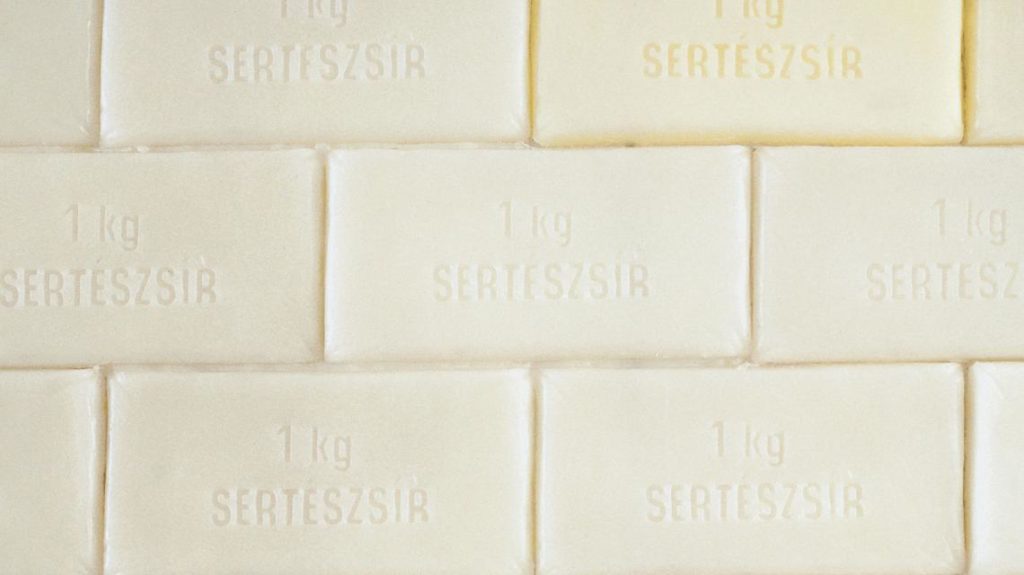

lined with these soft plastic bricks each representing a kilogram of pork fat to represent the fixed quota of goods that peasants were required to sell to the state at fixed prices. Eventually you reach a terrifying elevator ride to the basement. You’re engulfed in near total darkness as the elevator carries you down at a painfully slow pace. The only clear sight or sound is a video in which a guard calmly, dispassionately, and in a very matter of fact manner describes the execution process with the verdict usually arising from one of the many show trials that the government prosecuted.

When you reach the basement, if anything, the horror intensifies. Even though you’ve passed through an actual torture chamber, here,┬Āthe reconstructed prison cells leave no doubt about the human capacity for creating┬Āevil.

Pat and I spent perhaps two hours here and only touched on the volume of material. By the end, we were both emotionally wrung out and staggered back in the direction of the hotel. I think we stopped at the Opera House and this is when we learned that the production of Billy Elliott had closed. Although a tour of this beautiful building might have ameliorated some of the impact of the House of Terror, neither of us had the stamina.