Just Zagreb facts, Ma’am.

Although Zagreb’s Wikipedia page lists 17 city districts, Damir, who’s essentially a lifelong resident of the city, told us that it’s best to think of the city as having three major sections:

Novi Zagreb or New Zagreb – which developed mostly from Tito’s time forward. This covers the area from the airport to the south bank of the Sava River;

Donji Grad also Lower Town or Down Town starts at the north bank of the Sava and extends to the Main Square;

Gornji Grad or Upper Town spanning the stretch from the Main Square to the edge of Medvedica or Bear Mountain and is comprised of Kaptol and Gradec.

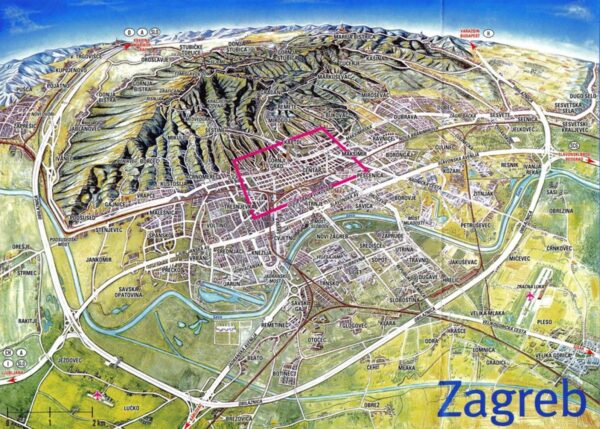

Both Donji Grad and Gornji Grad are within the center part of the city. Here’s a map for those who are more visual than verbal:

The area outlined in red is the city center where you’ll find Lower Town and Upper Town and the area south of the river just below the red outline is New Zagreb. We’ll spend our time within the red area. (I know it’s hard to read but if you click on the map {as on any photo in the blog}, you’ll see the larger version.)

Of course, you’ve all learned by now that I’m not satisfied with providing just a cursory look at a city so herewith is some more information about Croatia’s capital.

Andautonia, the oldest known settlement in the area, dates from Roman times and was located on the south side of the Sava River a bit southeast of the city today. The first mention of Zagreb occurred in 1094 when King Ladislaus 1 of Hungary established the Zagreb diocese in Kaptol. If you enlarge the map and look just to the east of Gornji Grad you will see Kaptol where the Cathedral and bishop’s residence were built on the southeast side of the hill. It’s one of the two main areas of the Upper Town.

The other, Gradec, became a free royal city by decree of King Béla IV in 1242. He granted the decree after Gradec resisted a Tatar attack and the fortress provided him haven. Some of the protective city walls built around Gradec between 1242 and 1261 in anticipation of another Tatar attack still surround part of the Upper Town but only one of the three gates, The Stone Gate, which we’ll see tomorrow, still stands.

It wasn’t until 1851 that Kaptol and Gradec joined to become formally known as Zagreb. However, as early as the first quarter of the 17th century the area had already become the political center of the region.

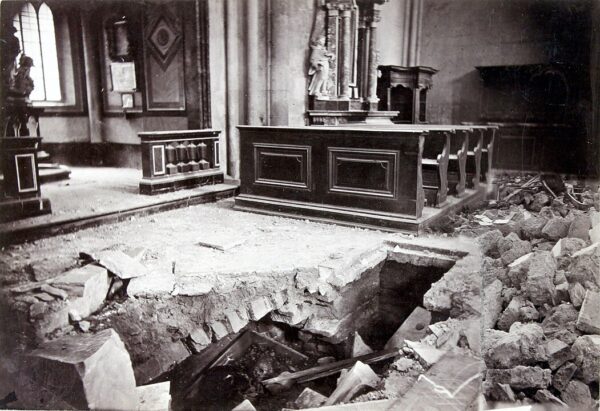

In 1880, the Great Zagreb earthquake, a magnitude six point three temblor centered in Medvednica rocked the city.

[Photo by Ivan Standl from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

An official report stated that, not counting churches and state-owned buildings, a total of 1,758 buildings were affected and 485 were heavily damaged. This sparked something of a building boom in the Lower Town where, beginning in 1899, a significant number of Art Nouveau buildings were constructed.

This building boom lasted until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Construction of railway lines helped Zagreb become one of the only towns in Croatia with a tram system. As the suburbs were thus connected with the city center, Zagreb experienced an enormous population boom in the 1920s – a period that saw the town grow by nearly 70 percent. Today, the city has a population of about 800,000 with 1,200,000 in the metropolitan area.

Zagreb in the Croatian War of Independence.

The background.

In April and May 1990, Croatia held its first round of elections in the face of already growing tensions between the Serbs, who favored a centralized union and the Slovenes and Croats who were among the first Yugoslav republics to move toward declaring their independence. The Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) – a political party headed by Franjo Tuđman – ran its campaign based on first achieving greater sovereignty followed by independence – topped the polls.

The first Croatian National Assembly (Sabor) of the present era convened on 30 May 1990 and now President Tuđman announced plans for a new constitution. After Tuđman’s election and the early moves toward independence, a Serbian Assembly was established in the village of Srb on July 25th as the political representation of the Serbian people in Croatia. This Serbian Assembly declared “sovereignty and autonomy of the Serb people in Croatia.”

Following a 25 May referendum, Croatia declared its independence effective 25 June 1991 and Serbian politicians left the Sabor. They followed that walkout with a declaration of autonomy in areas that would soon become part of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) intending to gain independence from Croatia. The RSK never attained any international recognition. Croatia’s declaration was suspended for three months, until 8 October 1991 because the Croats feared any outbreak of conflict might be viewed by the international community as a civil war rather than a conflict between independent states.

Recall also that the Serbs and Montenegrins had joined to form the Yugoslav National Army or JNA. The JNA Air Force attacked the Banski dvori (Presidential residence) and other targets in the Gornji Grad area of Zagreb as well as other areas in the Croatian capital city on 7 October 1991.

[Photo from Wikipedia By Roberta F., CC BY-SA 3.0,].

Despite evidence pointing to the contrary, the Yugoslav Defense Ministry claimed that the attack was staged by the Croatian authorities asserting that Croatian leadership had planted plastic explosives in the Banski dvori.

Continued skirmishes and foreign mediated truces followed during which time, as you remember, Tuđman, greatly expanded the size of the Croatian Army. On 19 December 1991, Iceland became the first country to recognize the new state of Croatia followed four days later by Germany.

Among the factors preventing the RSK from gaining even a hint of international recognition were the 1974 constitution and the Badinter Committee. The constitution essentially set the international borders as those that had been established internally by the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ). The AVNOJ was effectively the legislative body of the Partisans and in 1943 and 1945 established the parameters for the Yugoslav Federation.

The Badinter Committee was set up by the European Economic Community to guide European reaction to the deteriorating situation in the Balkans. One of their rulings was, “The boundaries between Croatia and Serbia, between Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia, and possibly other adjacent independent states may not be altered except by agreement freely arrived at…Except where otherwise agreed, the former boundaries become frontiers protected by international law.” Meaning, of course, that the Croatian borders were well established.

The war comes home to roost in Zagreb.

The United Nations brokered another truce in January 1992 and established the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) to monitor and enforce it. This truce lasted about a year during which time Croatia became a UN member state. Of course, none of this prevented Serbian forces from occupying much of Slavonia (recall the assault on Osijek).

In the spring of 1995, a well-planned Croatian military operation reclaimed all of the previously occupied territory in Western Slavonia. In retaliation, Serb forces attacked Zagreb with rockets (one of only a handful of times they assaulted the capital) on May first through the third.

In the mid-morning of 2 May 1995, without warning, several rockets struck locations in Zagreb. The targeted areas included the main square, several shopping streets, a school, the village of Pleso near Zagreb airport, and the airport itself. The attack resulted in five civilian deaths and at least 160 severely injured. Another rocket attack the following day struck the Croatian National Theatre at Marshal Tito Square and a children’s hospital. These attacks claimed two more lives and injured 54 more.

These casualties could have been far worse. In October 2013, eighteen years after the war ended, someone discovered an unexploded cluster bomb on the roof of the Klaićeva children’s hospital. Fortunately, the bomb squad of Zagreb’s police force disarmed it with no injuries.

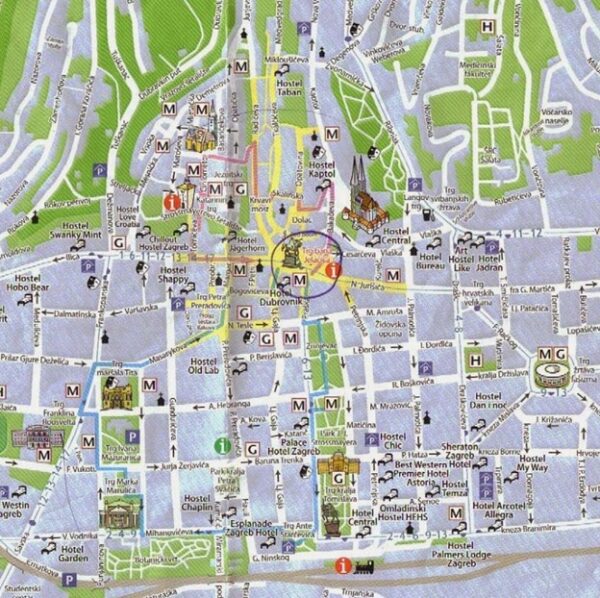

We arrived in Zagreb and had a brief ride around the U-shaped green center of the Lower Town (please ignore the circled area)

where the Botanical Garden at the bottom left of the map forms the base of the U. Look closely and you can also spot our home for the next three nights – the Palace Hotel Zagreb about halfway up on the right side of the U.

I should note that the shades of the leaves in the photo is due, in part, but not entirely, to the angle of the sun. We were beginning to see some signs of fall even though it was early August. Most of us rightly think of the Nordic or Baltic states as the northern part of Europe without considering how much farther north they are from the continental United States. The truth is that Zagreb, while it is about 1,500 kilometers south of Stockholm, is not where anyone but a Norseman might consider south. For comparison, it’s at a latitude that in the U S would place it slightly north of Billings, Montana so for Americans like me, it is north.

Tomorrow, we explore the city.