A roadside lunch, a famous cathedral, and ice cream.

Our first stop on the way to Karanac was for an early lunch at a spot that almost qualifies as a roadside attraction. My scribbled note says it was called Kotromanica (but I won’t guarantee the note’s accuracy). You see, I was so taken by the effort to create a rustic atmosphere

(apparently the cabins can be rented)

(apparently the cabins can be rented)

and

(where nothing says rustic like swans and a satellite dish) that I neglected to take a photo of the name. This was worth the stop for the ambiance, which was indeed memorable, but not for the food which was not.

(where nothing says rustic like swans and a satellite dish) that I neglected to take a photo of the name. This was worth the stop for the ambiance, which was indeed memorable, but not for the food which was not.

We followed lunch by making a brief stop in Đakovo mostly to see the Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul which is said to be the most important sacral object in Slavonia. (This downloaded photo isn’t how we saw the cathedral but it is a far superior look at it than the ones I took.)

Đakovo was among the first cities in Slavonia captured by the Ottoman Turks as they expanded their control of the area. The Turks gained control of Đakovo in 1536 and of Osijek by 1540. However, since they held the territory for only about a century and a half, this area didn’t see as many conversions to Islam as other Ottoman controlled areas on the peninsula. Eventually, the Habsburg Empire fought back and handed the Turks a significant defeat at the town of Sisak about 200 kilometers west of Đakovo.

In 1684, Pope Innocent XI created an alliance known as the Holy League that proceeded to fight the Ottomans for 15 years in what was known as the Great Turkish War (or War of the Holy League). By 1687, the Ottomans had essentially abandoned Slavonia so the region remained largely Catholic and in 1699 the Treaty of Karlowitz formally acknowledged Austrian control of the entire region.

The cathedral was built in 1866-1862 under Bishop Josip Juraj Štrosmajer (more commonly Strossmayer) whose name we will encounter more prominently a few days hence when we reach Zagreb. He was made a bishop on 8 September 1850 declaring his motto to be Everything for the faith and the homeland. And he carried that out.

In 1860, Štrosmajer became president of the People’s Party – a Croatian political movement that believed in the unification of all southern Slavs – that, at its peak, sent a significant number of representatives to the Croatian Parliament. He held the presidential post until 1873. Although he supported the Habsburg Monarchy, he focused on obtaining more rights for the Slavs within it.

Štrosmajer was known for using the money obtained from his diocese to fund the building of schools, galleries, and churches. In addition to building the cathedral in his seat at Đakovo, he was also instrumental in founding the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts in 1866, re-establishing the University of Zagreb in 1874, and the Štrosmajer Gallery of Old Masters in Zagreb in 1884.

As a religious leader, he challenged (though later relented) the doctrine of papal infallibility. Perhaps more importantly, in his efforts to unite the southern Slavs, he convinced Pope Leo XIII, to allow the south Slavs of Croatia and Dalmatia to retain Slavonic in the Roman Rite liturgy as well as in the Byzantine (Orthodox) Rite.

We walked down the relatively abandoned (it was Sunday, after all) main square. Some of us (including me) stopped for ice cream and others for coffee. I took Diane’s photo with a statue of the Croatian poet Luka Botić.

Hail, Hail, Slavonia (an obscure reference).

Now that you have an idea where we are on the map, let’s learn a little about the region as we ride from Đakovo through Osijek and on to Karanac. Riding through Slavonia, you can’t help but conclude that agriculture must play a significant part in its economy. As it turns out, although it makes up only a bit more than 22 percent of the country as a whole, Slavonia contains 45 percent of Croatia’s arable land and the county of Osijek-Baranja where we will spend our time, is one of the two largest agricultural areas of the region.

In addition to being Croatia’s largest producer of sugar beets, plums, and cereal grains, the region also supplies nearly half of the country’s legumes and apples. As we would learn later, the area also grows a lot of cherries and pears and has nearly a fifth of Croatia’s vineyards.

Croats comprise nearly 86 percent of the population. Serbs make up a bit less than nine percent and Hungarians claim about one-and-a-half percent. These groups comprise the two largest minorities. It wasn’t always thus.

Croats first settled in the area between the sixth and ninth centuries and were the dominant group for nearly 500 years before they formed a union with Hungary in 1102. For a short time beginning in 1527, Slavonia officially became part of the Habsburg Empire and the Hungarian and German speaking population steadily increased for about a decade when the Ottomans began their conquest of the area in 1536.

As I noted above, the Ottoman stay was relatively short so few in the population converted to Islam and the region remained mainly Catholic. The Serbs, while never making up as much as a fifth of the population, have been bounced back and forth and in and out of the region – sometimes by their own volition and other times not.

The first great wave of Serbian migration into Slavonia came in 1690 and was followed by a second wave in 1737-1739. After World War I, Slavonia became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and the government, seeking to repopulate the area after heavy losses in the war, encouraged the resettlement of large numbers of Serbs to the region.

That changed abruptly in World War II under the Nazi puppet regime of the Independent State of Croatia (these were the Ustaše) which displaced or killed large numbers of Serbs then replaced them with significant numbers of German speakers. Under Tito, people from other parts of Croatia as well as people from the mountainous parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro recolonized the area.

The 1991 census recorded a population consisting mostly of Croats and Serbs at 72 percent and 17 percent of the total respectively. Despite nearly always representing a relatively small minority in the area (particularly in the post World War II period), this didn’t deter the Serbian dominated Yugoslav National Army (JNA) from launching heavy attacks in the region with perhaps the most devastating assault launched on the city of Vukovar on the western side of the Danube River.

Vukovar was a once prosperous town with an economy based largely on trade, farming, food processing, and viticulture. The JNA held the city under siege for 87 days in 1991. During that time, together with Serbian paramilitary units they committed the largest massacre of the war to that point killing upwards of 250 people – mostly civilians taken from the Vukovar hospital – on 20 November 1991 and burying them in mass graves. Vukovar remained under Serbian control until 1998 when it was ceded back to Croatia but it has never regained its former prosperity.

During the Croatian War of Independence, both ethnicities migrated from the area in substantial numbers. Since the end of the war, many of the Croats have returned but most of the Serbs have not. The Croatian population has been further bolstered by Croat migration to Slavonia from Serbia and B&H thereby creating the larger Croatian majority seen today.

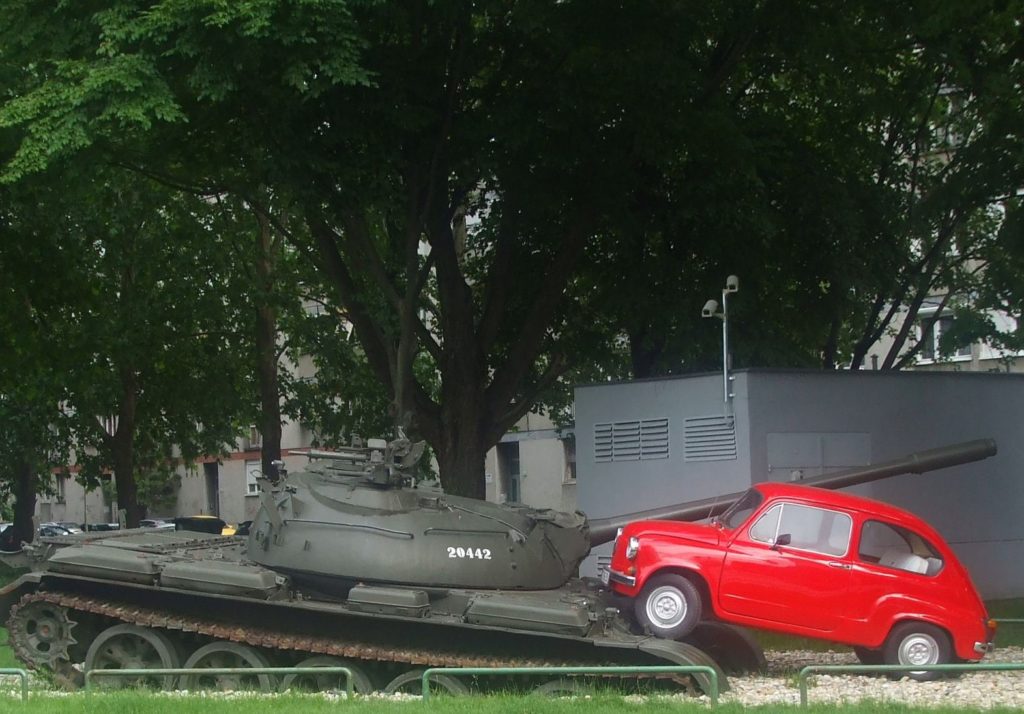

But Vukovar wasn’t the only city that saw major Serbian incursions into Slavonia. We drove through the city of Osijek where, as our group leader Damir reminded us as he pointed out a unique memorial, a contemporaneous video of one of the war’s most iconic moments surfaced.

The town of Osijek, determined to show that peace will triumph, turned the image on its head.