The driving distance between Salzburg and Prague is a bit less than 400 kilometers or between four and five hours. However, with a 09:00 departure, you might want to stop for lunch. And if you’re going to stop for lunch, why not do so at a UNESCO World Heritage city that sits a little more than halfway between the two. While you’re at it, you might as well take a little walking tour, too. Thus, we came to Český Krumlov.

How do you make a UNESCO World Heritage City?

Step one: Find a small town or towns,

built below a 13th century castle that’s the second largest in its country and,

that had been at the center of a feudal estate of one or more noble families who played an important role in the political, economic, and cultural history of the region.

Step two: Be fortunate enough to have both the castle and the town mostly unaffected by the myriad wars and periods of political neglect (such as the Communist Era in the former Czechoslovakia) that have raged around it.

Step three: Preserve the original layout paying particular attention to the characteristic castle-city relationship. Finally, carry out any necessary restoration work in strict compliance with international standards for historical heritage conservation. Congratulations, Český Krumlov.

A little history.

Apparently our driver was unaccustomed to reaching town from any direction other than Prague so when he made a few wrong turns we had the privilege of seeing bits of Český Krumlov that I’d guess few tourists ever see. We finally found our way to the central parking lot and walked up the long hill to meet our guide near the castle.

Humans have been here for some time. The area’s oldest settlement goes back to the late Paleolithic (70,000 – 50,000 BCE with the earliest mass settlement in the Bronze Age (1,500 BCE) and Celtic settlements in the Iron Age (approx. 400 BCE). Slavonic settlement has been dated from the 6th century represented by two tribes – Boletice and Doudleby.

Moving ahead to the late 12th century, Vítek of Prčice settled in this area of south Bohemia. (Consider Czech and Bohemian interchangeable.) At his death, Vítek divided his property between his four sons – Jindřich of Hradec; Vítek II senior, from whom the Lords of Krumlov descended; Vítek III junior, founder of the Rožmberk (Rosenberg) family; and, Vítek IV who founded the Lords of Landštejn. It’s depicted in the painting “Division of the Roses” and so named because each family’s coat of arms featured a rose.

[Division of the Roses from Krumlov.info].

A letter by Duke Otokar Štýrský in 1253 contains the first written mention of the town’s name. The oldest part, called Latrán (from the Latin latus meaning side), is not the central area bound by the river in the top photo above but rather grew up spontaneously alongside the castle and was likely populated by people who had some function working but not residing in the castle.

The part of the town most frequented by visitors came a bit later with the first written reference appearing in 1274. The area was almost certainly populated by people with Bohemian, Germanic, and even Italian backgrounds. Since the town sits at a distinctive meander of the Vltava or Moldau River, the most likely derivation for Krumlov is from the German ‘krumm’ meaning crooked. Typical of the time, the town took shape around a large central square.

In 1302 the Krumlovian branch of the Vítkovci died out and Jindřich von Rosenberg asked King Václav II (Wenceslav II) to override the law of escheat (that would have passed the lands to the king) and vest the Krumlovian estates to the Rosenbergs who later made Krumlov their main residence. Their presence turned out to be a boon for the town which was granted the right to mill, brew beer, and hold markets. Jindřich’s son Peter the First, a shrewd politician, also fared quite well.

[Peter I Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Not only did he oversee the construction of Saint Vitus Church in Krumlov but also the hospital by the church of Saint Jošt in Latrán and the Chapel of Saint George within the castle that served the orders of Saint Clare and Saint Francis. Then, according to one source, in 1334 at the request of King Jan Lucemburský he invited the Jews to the town, gave them a special street, and had them serve as chamberlains responsible for the administration of Rosenberg’s finances that flourished under their guidance.

But by the late 16th century, the Rosenberg family’s fortunes began to wane both literally and figuratively. Throughout his rule, Wilhelm von Rosenberg, who united the towns of Latrán and Krumolv in 1555, initiated the reconstruction of the town’s houses and castle into a Renaissance style. He created considerable family debt but gave the town a unique appearance I’ll discuss below. By 1601, Peter Vok von Rosenberg had to sell the town to Habsburg emperor Rudolph II to pay his massive debts.

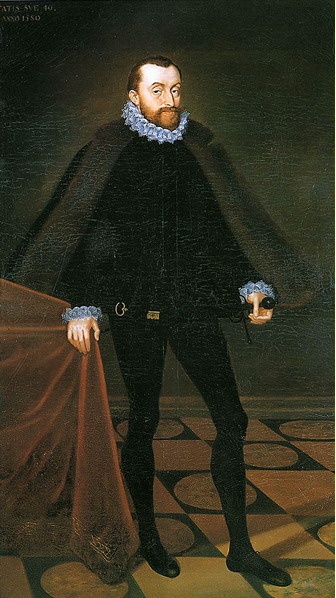

[Peter Vok von Rosenberg from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Needing financial support during the Thirty Years War, Habsburg emperor Ferdinand II vested the town to the Eggenberg family in 1622. They controlled the town for three generations before dying out at the beginning of the 18th century. Their successors were the Schwarzenbergs who lifted the town’s social and cultural profile while preserving its Baroque and Renaissance character.

As our guided tour came to a close and we left the castle, we came upon what I thought was one of the sadder sights of the morning.

This is the moat of the castle and it houses at least two bears who, while I acknowledge anthropomorphizing, looked sad and bored. According to Amusing Planet,

The Rosenberg family had a long association with bears. Legend has it that the Rosenbergs were related to the noble Italian family of Orsini, whose family name comes from the Italian word “orsa”, which means she-bear. The bear motif is also found in the Rosenberg’s coat-of-arms, in which two bears are shown as shield-bearers.

Bear-keeping at the Český Krumlov Castle started during the time of Wilhelm von Rosenberg, in the latter half of the 16th century.

However, the site also points out that through most of the 19th century, the moat had no bears until they were returned in 1907. Confined to a concrete pit, the bears only purpose seems to be as objects for tourists to gawk at. I took one other photo because, well, anthropomorphizing.

Is it an original or a knock-off?

In the section above I noted that Wilhelm von Rosenberg incurred so much debt in trying to transform Krumlov’s architecture into a Renaissance style that he essentially bankrupted his family. Not only the Rosenbergs but those in the town couldn’t truly afford to build or maintain the castle and their homes in that architectural style. So, they did the next best thing: They painted the façades. And this you see all over Krumlov – from the castle,

to the town gate between Latrán and Krumolv,

to some of the buildings on the side streets.

It left me with the feeling that I was walking through a back lot at Paramount all false fronts and no substance.

A full traditional lunch.

Earthbound had planned a group lunch that I can only describe as full, traditional, and heavy. The small restaurant accommodated most of our group at one table but I seem to recall Shlomit, Kathlene, and perhaps one or two others sitting elsewhere. My note says I had all the courses – salad, soup, duck as a main, and dessert. The heaviness of the meal made Shlomit’s ‘Todd-frugal’ announcement both welcome and unwelcome.

She told us that the bus had been booked through 19:00 so we had the time to spend an extra hour or two wandering through Český Krumlov. For me, this was

Todd-frugal because if you’ve got it until 19:00 then you may as well use it until 19:00.

Welcome because after that lunch, an hour or two of walking felt like a necessity.

Unwelcome because it meant even less time in Prague.

I’ll add that Český Krumlov made a terrific first impression on some people particularly those who had extended their planned stay in Czechia for a few days beyond the trip’s scheduled end. Some thought they might enjoy a return day trip. The extra two hours convinced them their time would be better spent otherwise.

Since I’m running up against my self-inflicted word limit, I’ll save the story of my reunion with my Czech mate Peter for the next post. (You couldn’t have thought I’d go the whole post and not make a single pun of this sort. In fact, you should be relieved that I held myself in Czech after hours in the country and nearly reaching the end of this post.) But as we ride the bus from Český Krumlov to Prague, I think we’ll pass the time with another look at Antonio Salieri.

And here’s the photo link for the remaining photos from this Friday in May.