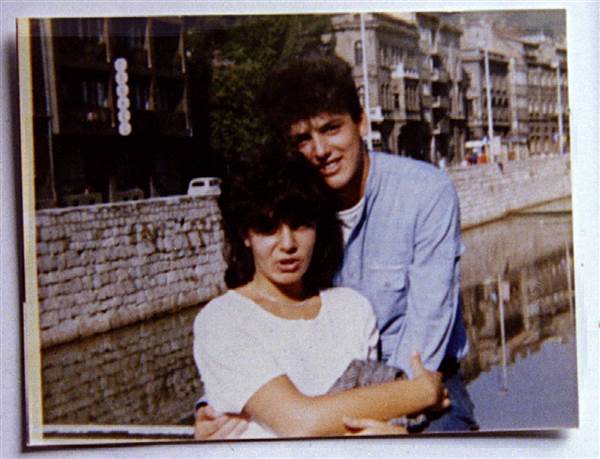

If I haven’t yet broken your heart, perhaps I will with a more personal story of two people – Admira Ismić and Boško Brkić.

[Photo from Sarajevo Times.]

Boško was a Bosnian Serb just a bit shy of his 25th birthday. His girlfriend Admira was a Bosniak who had recently reached that milestone. On 19 May 1993, during a very tenuous ceasefire, they were attempting to cross the Vrbanja Bridge – the one that is now named the Suada and Olga Bridge in honor of the siege’s first two victims.

According to one eyewitness, “The girl was carrying a bag and waving it. They were running and holding hands. It looked like she was dancing,” the witness said. “Suddenly, I heard the rifle shots. They fell to the ground.”

Another described the scene this way: “As soon as they were at the foot of the bridge, a shot was heard. The first bullet hit Boško Brkić and killed him instantly. Another shot followed and the woman screamed. She fell down wounded but was not killed. She crawled over to her boyfriend, cuddled him, hugged him for 10 or 15 minutes and died.”

As was so often the case, each side blamed the other for breaking the truce. The truth never came to light and no one was ever charged. Their bodies remained on the bridge for eight days while the two sides bickered over who was responsible. Finally, Serbian forces surrounding the city forced some Muslim prisoners to retrieve them sometime during the night of the eighth day.

Mark H Milstein took a photograph that inspired Kurt Schork of Reuters to file a report about them that gained worldwide attention and they were the subject of a documentary called Romeo and Juliet in Sarajevo. You can watch it if you follow the link. Victor Harrington wrote a fictionalized account of their lives in his novel Charmer Boy, Gypsy Girl. The couple are buried together in Lion Cemetery.

[Photo from Tuzlanska.ba].

Killing a culture.

In addition to the cost in human life, the ultimate toll of the siege to cultural artifacts and to buildings is equally incalculable. I’ve written of the destruction of the City Hall and the manuscripts and records that were lost on the night of 25 August 1992. Months earlier, in May, the Serbs had targeted the Oriental Institute in Sarajevo which lost over 5,000 bound manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, and local Arebica (Bosnian in Arabic script), as well as tens of thousands of Ottoman-era documents and what was considered to be one of the richest collections of Oriental manuscripts worldwide.

One estimate stated that more than 23 percent of the city’s buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged. Another 64 percent were reported as partially damaged and 10 percent as slightly damaged meaning that 97 percent of Sarajevo’s buildings were damaged in some way.

Some of you might have heard about Steven Galloway’s novel The Cellist of Sarajevo. The novel is based in part on a true story. As this Mikhail Evstafiev photo shows, even in the midst of all this devastation, the spirit of Sarajevo persevered.

The Tunnel of Life.

The Siege of Sarajevo officially began on 5 April 1992. In short order, the combined forces of the JNA and the VRS under the command of Ratko Mladić had blockaded the city cutting off not only access and egress but all utilities gas, electric, and water. Under intense international pressure, the Serbs conceded control of the airport to the UN at the end of May 1992. Although the 70,000 ARBiH forces in Sarajevo greatly outnumbered the Serbian forces, the rapidity of the Serbian attacks combined with their strategically superior position and a UN arms embargo that had left the Bosnian regulars disadvantaged with respect to arms left the ARBiH and the Sarajevans unable to break the siege. So, they needed to develop alternatives to ensure their survival. One was the Sarajevo Tunnel.

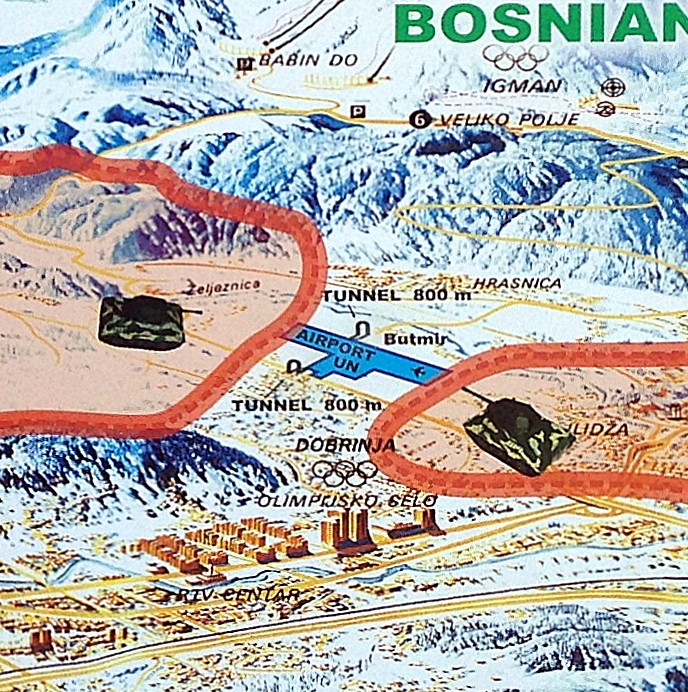

Planning for the tunnel began in late 1992 and work started on the first of March 1993. The top-secret operation was called “Objekt BD” because the goal was to link Butmir with Dobrinja. The tunnel would be approximately 800 meters long. I’ve enlarged a section of the siege map so you can better see its location and length.

Looking at the map, you can see that, although the territory was demarcated as under Bosnian controll, anyone trying to cross its length was either blocked by the UN at the airport or would be an easy target for the Serbian forces on the hills above. The First Corps ARBiH led the project and dug to a maximum depth of five meters in the section below the airport. The height of the tunnel ranged from about 160 centimeters (not even high enough for me to stand upright) to 180 centimeters. At no point was it wider than one meter.

Beginning at both ends, digging entirely by hand with shovels and picks, and using wheelbarrows to cart away more than 1,200 cubic meters (42,000 cubic feet) of dirt and other detritus, while working 24 hours a day in eight-hour shifts, they completed the first phase of the tunnel in precisely three months when the two sides met on 30 June. The tunnel, barely more than a small muddy tract prone to flooding, had its first use the next day. Initially anything moving through the tunnel moved either by hand or on the backs of soldiers. In time, the army laid a small railway track allowing the use of small carts. They eventually added an electric cable, a telecommunications line, an oil pipeline, water pumps and permanent lighting.

In addition to supplying food, supplies, and fuel to both the army and the civilian population, the tunnel also served as a principal means of circumventing the UN arms embargo and providing weapons for the ARBiH. But the Tunnel wasn’t merely a route to smuggle supplies and arms. People, including UN forces also used it. Some estimates are that over the duration of the war, between two million and three million Bosnians and UN soldiers made the two-hour journey through the tunnel. This equates to between 3,000 and 4,000 per day who traveled in groups ranging in size from 20 to 1,000. Approximately 400,000 Bosnians used it to flee Sarajevo. Remember, all of this was against a backdrop of more than 300 shells per day falling on the city. The fact that the tunnel never collapsed is remarkable.

The Dobrinja tunnel entrance was in an apartment building. On the Butmir side, a local man named Bajro Kolar gave use of his house for the tunnel entrance. Kolar didn’t view his decision as a sacrifice. In an interview he said, “Whatever we had, we gave for the defense and liberation of Sarajevo.” It’s here that the Tunnel Museum stands today.

On a visit, the first place you stop, is a small center that runs two short, silent videos compiled from wartime footage of the city under siege and of the construction and passage through the tunnel. While we were there, the audience’s awed silence was broken only by an occasional sniffle.

The house that hid the entrance is still owned by Bajro Kolar and his family and, other than the pockmarks vacantly staring at you like the eyes of some of the more than 13,000 people killed, it is probably as nondescript as it likely was a quarter century ago.

Upon entering the house, you see some of the munitions that were dropped on the beleaguered city

(that’s our city guide in the photo);

and you can walk along 20 meters of the preserved tunnel:

You exit the tunnel itself into a museum exhibiting tools, documents, photos, miscellaneous military paraphernalia, and other items that were used to survive the siege.

Is this a pleasant place to visit? No. Is it a life affirming place that makes the unstoppable determination and resourcefulness of Sarajevo’s citizens tangible. Yes, without question.

On our bus ride back to the Old City, our guide told us in frank detail about her personal experience as a 10- or 11-year-old girl helping her mother tend to her much younger sister. I’ll spare you the details but will tell you that her story is every bit as harrowing and as life affirming as the one of the Sarajevo Tunnel.